Why Mutual Funds and 401(k)s May Be Hazardous to Your Wealth

A freewheeling conversation with the author of 'Empire of the Fund'

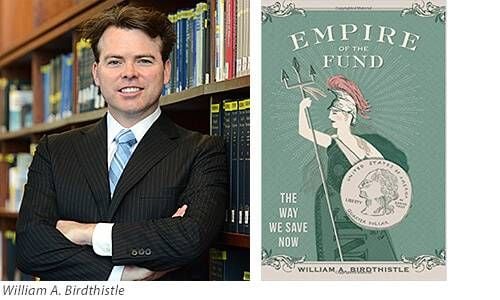

You’ve got to applaud a law professor who has turned his new cautionary book about mutual funds and 401(k)s into a rap video. That’s exactly what William A. Birdthistle (great name, too!) has done; you can watch it at the end of this blog post.

Birdthistle’s pun-titled exposé, Empire of the Fund: The Way We Save Now, takes sharp jabs at how the nation’s mutual funds — which hold $16 trillion in assets — and 401(k)s are run. He’s especially peeved about their “perverse” system of fees. He’s not alone: More than a dozen lawsuits have been filed challenging 401(k) fees since last September, according to Pension & Benefits Daily.

But the Irish-born professor at Chicago-Kent College of Law is utterly compassionate towards small investors and employees. He knows they’re trying their best to save for retirement, but doesn’t think they’re getting much help to do it well.

The Failure of the U.S. DIY Retirement System

“More and more studies have shown irrefutable evidence that in the experiment of putting all this money in the hands of individual investors, the results just aren’t there,” Birdthistle told me during our freewheeling interview about the book. “One third of Americans have no retirement savings and, of the cohort about to go into retirement, they have $111,000 on average, which works out to about seven grand a year.”

During our conversation, Birdthistle talked about the problems he sees with funds and 401(k)s, how he'd change things, why he'd like employees to get licenses before choosing retirement-plan investments and the brilliance of TV's John Oliver. Highlights:

Next Avenue: What’s the overall message of your book?

Birdthistle: That mutual funds are good, but they’re not charitable institutions. They’re for profit. You can lose money and you will. That message should be repeated again and again. And people should always be on guard for that.

Does America’s retirement system expect too much of people? And do Americans know how to save and invest wisely?

Yeah, it does. And no, they don’t. Even if you were an incredibly well-informed investor and paid a great deal of attention, it’s very hard to succeed in this system.

We moved from a system with large pensions and Social Security to one where it’s do-it-yourself. That’s a massive change, with almost zero commensurate change to educate people about how to do this. We said: ‘Listen, everybody can do this and they’ll figure it out.’ Of course the answer is: A lot of people won’t do well in this system and all the studies have suggested it’s not going well.

Why are we doing so poorly saving for retirement?

There are a series of hurdles and a large percentage of people fall into each one.

Step one is: Do you have a job and if so, does it have a 401(k) or 403(b) and, if so, are you enrolled in it? A lot of people fail right there. Then, if you are enrolled, have you selected a reasonable amount of money to go into the account? And the third hurdle is the investment election. As an investor, you need to focus on funds that are the best choices. But there are 8,000 of them, which is where people can fail.

Mutual funds have made a lot of small investors a lot of money and increased how much they have in their retirement funds. Why are you so down on them?

I’m not; I think they’re a terrific and important way to invest. But of the 8,000 funds, about 7,700 are actively managed. And anything with active management is a disaster for investors, generally [due to higher fees and their inability to outperform the market consistently]. So you should immediately remove about 90 percent of funds from a prudent investor’s retirement portfolio.

Index funds are excellent for most people. I want to see more done to get people into the right kind of index funds — ones with very low fees.

Target-date funds were supposed to be a great way to help people save for retirement with a set-it-and-forget-it system. What do you think about them?

I think they’re probably the right choice for many people. But as with all good things, you should be aware of their limitations. 2008 was a stark eye-opener for how many target-date funds took a big hit, especially the ones that should have been very conservative.

Why don’t more investors look for funds with low fees?

The problem is many people have the intuition that paying the least amount is not the way to get good performance. Paying the least for a haircut or for tacos usually is not a great way to go. But mutual funds are a very unusual market; it’s one of the only types where price and performance are inversely correlated. That’s hard to get your head around.

Unlike most products, fees are what ruin performance.

You say there are ‘perverse incentives’ for mutual funds. What are they?

Mutual fund advisers are compensated as a percentage of their assets under management. It makes all the sense in the world why they have an incentive to expand their funds; they make more money. The problem is, it’s hard to make smart investment choices as you expand your portfolio.

Then they charge their investors 12B-1 [marketing] fees to market to new investors. That’s crazy! Why would you as an investor want your money to be used to bring in more people?

You’re also concerned about a form of mutual fund and 401(k) compensation called revenue sharing. Why?

Revenue sharing arrangements are essentially kickbacks. The fund advisers pay the intermediaries who are dealing with investors to push their funds. It’s when someone hands you a brochure at a place like Schwab or E*Trade and says ‘these are our select funds’ or ‘the ones we recommend.’ Or it's how funds get on a 401(k) list.

Are investors told about this?

As long as it’s disclosed, it’s OK. Rather than giving investors hundreds of pages, maybe funds could boil it down to a couple of pages and emphasize the dubious kinds of arrangements, like revenue sharing.

The fund industry would say: 'We couldn’t be more transparent. Our expense tables tell you everything.' But if you gave the average person a prospectus, he would have a hard time figuring out what he pays; you see 10 funds with six different share classes, so you need to know which fund you held.

And then you see the weird development of waivers of fees. You might think: ‘That’s great! I’m paying less than I might!’ The problem is the footnote says the waiver is in effect until the board says otherwise, so the fees could bounce back up. It’s a quiet way to raise fees whenever they want to.

You think expenses should be shown in prospectuses as the dollars the investors pay, not percentages. Why?

No question. [Vanguard founder] Jack Bogle said many times the greatest scheme the industry pulled was quoting fees in percentages, or basis points. People say, ‘It’s so insignificant, I don’t need to think about it.’

And what do you think of Exchanged-Traded Funds, or ETFs?

I think ETFs are like very sharp knives; they’re excellent in the hands of experts and a painful mess in the hands of amateurs. A cheap target-date fund can do a much better job.

What's the danger of ETFs compared to mutual funds?

Mutual funds are regulated about what they can contain for leverage and where their portfolio can be invested. ETFs can be highly leveraged. Then you wander into the sharp area of the cutlery section, and the risks of getting things wrong are so much higher.

Also, some sponsors are creating preposterous ETF indexes. One was a Brazilian pharmaceutical company index and there are only like six of those companies. The point of an ETF is a diverse portfolio and six ain’t diverse.

Let’s talk about 401(k)s. Why do people who work for big employers have better 401(k)s than other people?

The biggest corporations have the sophistication to choose the best funds and the best-priced funds for their 401(k)s. But anyone at a small- or medium-sized company or who is self-employed or unemployed is completely getting the bad end of the spectrum.

What do you make of the recent study that found that fund companies tend to favor their own funds when choosing the menus for the 401(k)s they administer and tend to keep the funds on the menu even when they are underperforming?

[Laughs.] I read that as dog bites man. Of course they do. It doesn’t surprise me at all.

You have a pretty provocative idea in the book, saying that people should be required to get licenses before they’re allowed to invest in their 401(k)s. Tell me about that.

I’m sure the attacks on this will come fast and furious.

I think if you want to use a 401(k) plan and put money in anything other than a target-date fund or a broad-based index fund, you ought to be aware of what’s going to happen. And one way to do that is with a license. You’d take a test when you open the 401(k). This also says: ‘Through these gates, there be dragons.’ If you’re going to choose your own investments, you could lose money and you should be aware of that. Relatively modest licensing would convey a sense that something important is about to happen.

John Oliver recently took the retirement industry to task in his HBO show. What did you think?

I hope it's part of a drumbeat. People are coming to grips with the idea that the system is more complicated than we give it credit for.

I wish there were more John Oliver pieces out there.