How Do We Balance Autonomy and Risk for Older Adults?

Finding that balance takes guts, as caregivers often learn

Georgia Dyson of St. Paul, Minn., died in March after suffering the gradual shrinkage of her world. Through it all, “she always relished her independence,” her daughter Christine Dyson Dahn said.

Over Dyson’s 84 years, her spine twisted in two directions from degenerative scoliosis. She had cataracts, high blood pressure and congestive heart failure. She endured a double bypass heart operation, a mitral valve repair, a pacemaker, two hip replacements, a catheter, a hearing aid, dentures and, as you can imagine, periodic depression.

Despite all of that — and despite some misgivings about Dyson’s safety — family members did whatever they could to support her, insisting at each crossroads that she be allowed to get back to her routines.

“We wanted to respect that fire in her, but we worried about her,” Dahn said. “What if she went out in her wheelchair and got hit by a car?”

Balancing risk and autonomy is one of the toughest things that caregivers do, whether they are professionals or family members. It’s especially difficult when the people they care for cannot advocate for themselves.

Quality of Care or Quality of Life?

Each time Dyson’s health faltered over the years, it whittled away at her autonomy. When she reluctantly moved into assisted living for the first time in 2004, she insisted on cooking her own meals. Eventually facility management put an end to that because she was spilling so much food on the carpet and they worried she would hurt herself.

Yet Dyson never gave up trying. When her family packed her belongings in 2010 for a move to a nursing home, they discovered a corncob in a coffee pot. She had tried to cook the corn that way after losing her kitchen privileges.

Saskia Sivananthan, a consultant with the World Health Organization’s Global Dementia Team, knows what it’s like to suffer the indignities of nursing home living. As a young researcher in 2014, she checked herself into two different nursing homes in Ontario, Canada, for her work on a doctoral thesis. Staff members had instructions to treat her as they would any other resident, following all the standard policies and procedures. What Sivananthan found is that there's a big difference between quality of care — the focus of many nursing homes — and quality of life.

The realization struck her at breakfast one day. She missed the scheduled mealtime and had to eat in the lounge as a staff member stood by monitoring her every bite lest she choke. The standard protocol made no sense in her case and she was uncomfortable being observed so closely.

“Most nursing homes [in North America] have lunch, dinner and breakfast at a certain time,” said Sivananthan. “You would never do that in your own home.”

Moving Toward Person-Centered Care

Nursing homes in the U.S. and in Canada, where Sivananthan lives, evolved from a medical model, she explained. They document their residents’ well-being with standard health measures. By contrast, she noted, quality of life measures are “notoriously difficult” to assess.

In the United Kingdom and some European nations like Denmark and the Netherlands, the focus is more on personal autonomy, Sivananthan said. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have been moving in that direction as well, stressing what the health care industry calls person-centered care. It boils down to assessing an individual’s needs and desires and incorporating them into a care plan. The receivers of care must be included whenever possible in decision making about their care, even into the stages of moderate dementia.

Difficult behaviors often are a form of communication, Sivananthan said, so caregivers need to assess what triggers the behaviors and then consider whether the environment can be managed, rather than restricting people from what they want to do. She recalled the case of a man who wandered, a common problem for people with dementia. The nursing home staff discovered he’d been a painter. So they set up a room where he could paint whenever he liked, and it satisfied his need for a place to go.

'There’s Nothing Wrong with Wanting to Be on the Floor'

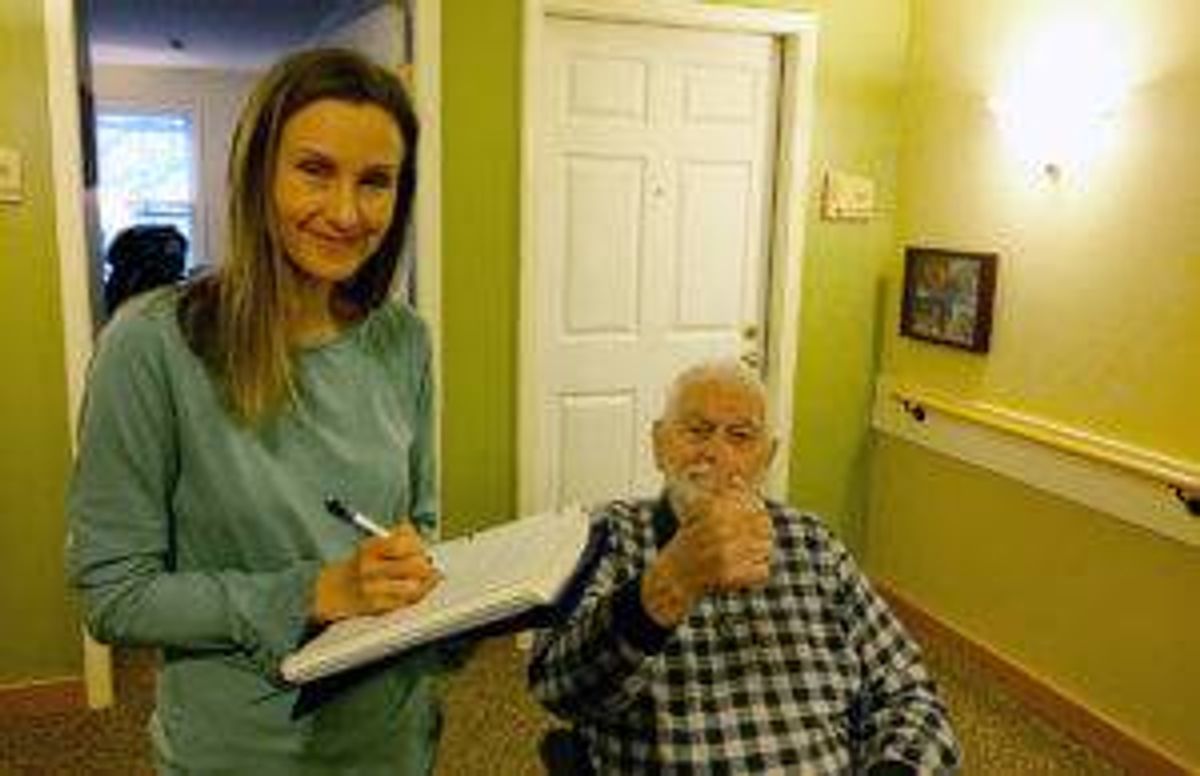

Linda Irgens of Maplewood, Minn., ran into a similar situation with her dad, Richard Irgens, recently. He's an 87-year-old former Marine, a retired commercial airline pilot and was an avid hunter and fisherman. But health problems including vascular dementia forced “Papa Dick’s” move to a nearby nursing home.

The staff there called Linda to say her father was refusing to leave the main floor of the nursing home and return to the locked memory-care unit. “He had his hat and coat and his keys, and he was determined to get out of there,” she said. He told her, “They won’t let me out of this place!’” She asked the staff to respect his needs and let him go out on the patio.

“He’s an outdoorsman and he’s always needed some access to fresh air and nature,” Linda said. “I told them I wanted him to have every risk possible, because that’s an indicator of quality of life.”

She added: “He’s been thrown out of planes. It’s OK, you don’t baby a lieutenant colonel, for God’s sake.”

Another time, the staff found her dad on the floor of his apartment. Assuming that he had fallen getting in or out of bed, they debated whether to remove the bed frame to lower the mattress. Linda balked. Her dad had told her that he just wanted to lie on the floor. “And there’s nothing wrong with wanting to be on the floor,” she said.

Can We Accept Risks?

Chris Perna, president and CEO of the Eden Alternative, an international nonprofit that provides training and advocacy to improve quality of life for people who need help with daily living skills, said professional caregivers have to assess each person individually in making care plans and “can’t just make unilateral decisions” for, or about, people. Perna’s New York–based organization teaches the principles of person-centered care.

He says good things can happen when older people are allowed to live more autonomous lives, “but it takes guts.” Often, it presents risks not only for care recipients, but for caregivers, who may be blamed when things go awry.

That fear can’t be allowed to take over, said Linda Crandall, executive director of the Pioneer Network, a nationwide coalition that also offers training and support to help elder-care communities shift from an institutional care model to a person-centered one. The New York–based Pioneer Network emphasizes autonomy for those receiving care. “Taking risks is a normal part of life,” Crandall said. “Care partners,” as she calls caregivers, must get to know the individual and understand how that person wants to live, realizing that it might change over time. The goal is to help someone be both happy and safe.

“The question is not, ‘What do I let her do?,’ but rather, ‘How do I support her?’” Crandall added.

Caregivers must use the least restrictive means possible when limiting someone’s activities. A review of the literature on caregiver liability indicates that a carefully constructed care plan can reduce liability if things do go awry. The plan should address the risk tolerance expressed by the person getting care, and by any of that person’s designated surrogates. The care plan won’t protect caregivers who are negligent, however, or professionals who provide substandard care. Wanton disregard for a vulnerable adult’s safety also could lead to prosecution under state elder abuse laws.

'It’s Their Life'

The right balance is not easy to find, said Rev. Katherine Engel of St. Paul, Minn. She cared for her mother, Frances Wachter, who died this year at age 81 after living with moderate cognitive impairment and other health issues. At her mother’s insistence, Engel moved Wachter out of assisted living and into an apartment of her own, despite the fact that she fell sometimes and broke things, including her pelvis once.

“There’s no dignity in falling and laying down on the sidewalk,” Engel said. And yet, “it’s their karma. It’s their life.”

Stacy Waskosky, of Maplewood, Minn., said her family tried for decades to care for her paternal grandmother, Annette Savage of Indianapolis, who had early-onset dementia. An increasing regimen of medications seemed to be making things worse. Savage grew angrier and kept running away from her assisted living facility, resulting in even more medications. She died in 2008 at age 92.

Reflecting back, Waskosky said that “everything was done in such small steps that you don’t realize until the very last minute that you’re limiting their freedoms.” The routines the facility set up for Savage were meant to be comforting and slow her decline.

“But when it’s not you that defines those rituals and routines, it’s devastating,” Waskosky said.