How the Pandemic Is Making the Retirement Crisis Worse — and What to Do About It

Experts explain the troubling ripple effects as well as reforms to deal with them

The coronavirus crisis has torn the Band-Aid off the financial fragility of many Americans. With an unemployment rate between 15% and 20%, bank accounts draining, and the Dow down 23% in the first quarter, things are dreadful for millions of people. But Americans in their 50s and 60s nearing retirement may be among the most endangered.

Many already weren’t on track for retirement, with little or no savings. Now, the COVID-19 downturn threatens to further undermine America’s vulnerable public and private retirement systems. Long story short: the pandemic is making the retirement crisis worse.

Without strong public policy initiatives, experts say, the already too numerous ranks of the financially insecure will swell even further. But, they add, a few smart and urgent reforms could bolster Americans’ financial security later in life.

“Even prior to the pandemic, things weren’t rosy.”

“The building blocks are there. They are available. The rules we use, and the access to them, are messed up,” says Kurt Winkelmann, senior fellow at the Heller-Hurwitz Institute at the University of Minnesota and co-founder of the investment research firm Navega Strategies.

Our Commitment to Covering the Coronavirus

We are committed to reliable reporting on the risks of the coronavirus and steps you can take to benefit you, your loved ones and others in your community. Read Next Avenue's Coronavirus Coverage.

The Fragile Retirement House

Think of America’s retirement system as a poorly constructed house that has deteriorated with time. Social Security is the financial foundation of retirement, but its trust fund is being rapidly depleted. State and local government pensions were underfunded by $1.2 trillion before the pandemic, according to researchers at the Pew Charitable Trust. About half of private-sector workers lack access to a 401(k) or other employer-sponsored retirement plan.

“Even prior to the pandemic, things weren’t rosy,” says Olivia Mitchell, executive director of the Pension Research Council at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Pre-COVID-19, Mitchell’s retirement mantra for the public was: Work longer, save more, expect less. “But I say it now with a vengeance,” she notes.

One reason why: the disturbing calculation from Michelle Seitz, chairman and CEO of Russell Investments. a global money manager.

Roughly 75% of heads of households ages 55 to 65 had almost no chance of being able to fund their retirement needs out of savings before the pandemic, Seitz noted during a recent Milken Institute webinar. But in the past few months, their finances have been deteriorating, with savings ravaged by market volatility, strapped workers tapping their 401(k)s to pay bills and near-retirees losing their jobs.

The Pandemic's Blow to Retirement Accounts

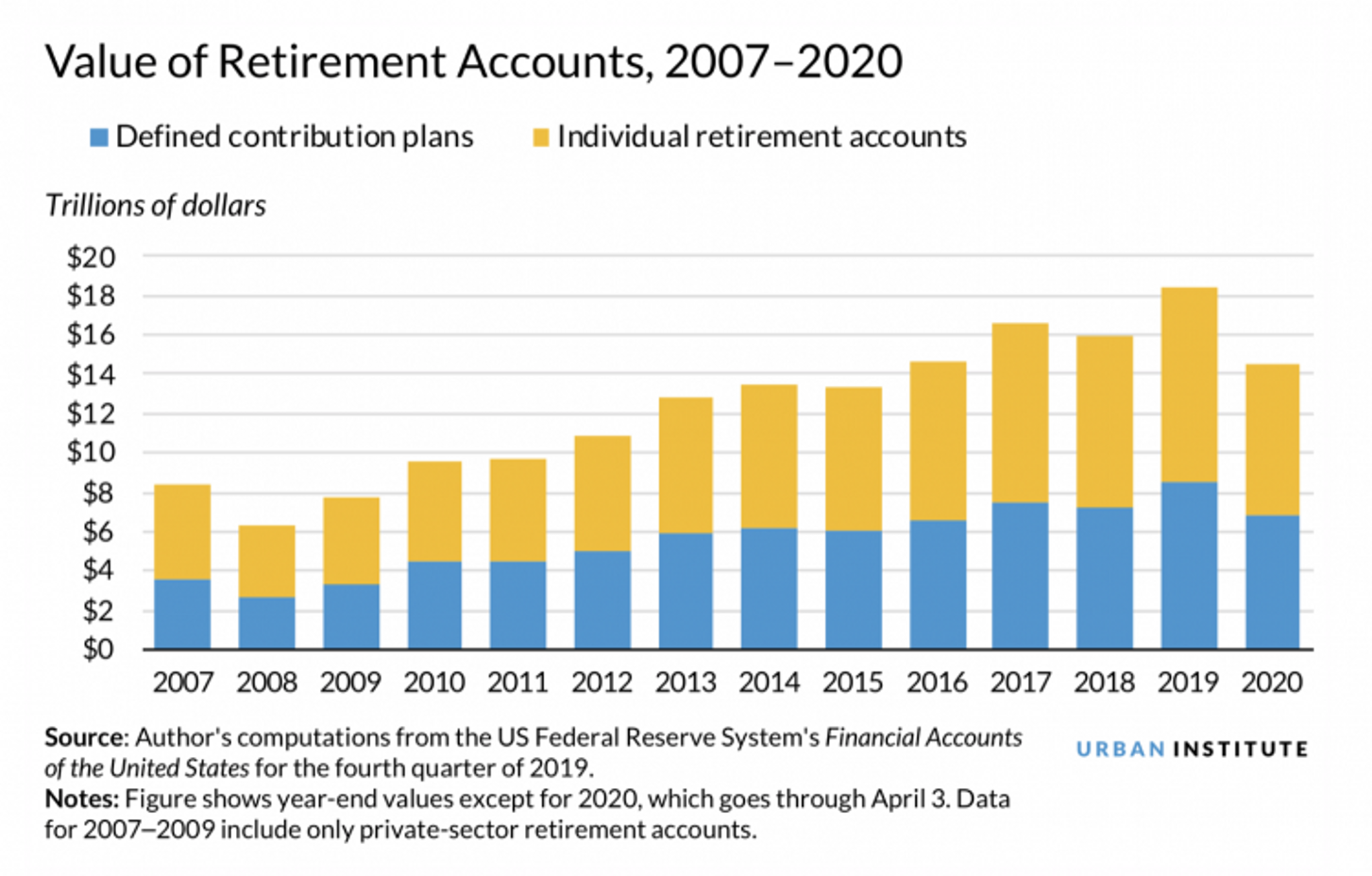

Richard Johnson, an Urban Institute think tank analyst, computes that the value of Americans’ retirement accounts has shrunk from over $18 trillion in 2019 to roughly $14 trillion now.

Fidelity Investments says the market downturn of 2020 has caused average 401(k) balances to fall 19% from the fourth quarter of 2019 and average Individual Retirement Account balances to drop 14%.

On top of that, some major employers with more than 300,000 participants in their 401(k) plans have started suspending the matches they make to employees’ contributions in them. This effectively lowers their rate of return and the potential growth of their accounts. Among the suspenders, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College and the U.S. Department of Labor: Best Buy, Choice Hotels, Lands’ End, Sabre and Tenet Health.

These researchers peg the potential date of the Social Security Trust Fund’s depletion at 2029.

The unprecedented speed of the job-market collapse could push more older workers to file early for Social Security, despite a steep financial penalty for doing so. Social Security benefits are more than 75% higher if you wait until 70 to start claiming rather than 62, the first year you can.

Sure enough, a new paper by three economists (“Labor Markets During the COVID-19 Crisis: A Preliminary View”) found a sharp increase in the number of surveyed unemployed people saying they’re retired — from 53% in the pre-COVID economy to 60% now.

What Can Be Done

To head off the growing risk that the pandemic will condemn the next generation of retirees to financial insecurity, experts say, the first step is reforming Social Security.

At a minimum, that means shoring up the Social Security Trust Fund’s finances to prevent insolvency. Beyond that, it could mean expanding benefit payouts for the neediest.

The 2020 Social Security Trustees Report, prepared before the pandemic, predicts that the Social Security Trust Fund will be depleted in 2035. At that point, according to projections, payroll taxes would only cover about three quarters of promised benefits.

That may be a rosy scenario.

A new study from the nonpartisan Bipartisan Policy Center think tank maintains that the brutal pincers of slow wage growth and extended unemployment brought on by the pandemic will put additional strain on the system’s finances. These researchers peg the potential date of the Social Security Trust Fund’s depletion at 2029 — a mere nine years away.

Allowing the Social Security Trust Fund to run out “would be catastrophic,” said Marcie Frost, CEO of CalPERS, the giant California public sector retirement system, at the Milken Institute webinar. “This is a solvable problem and has been for decades.”

One step that Congress and President Trump have taken to help Americans with money emergencies from the pandemic could actually enlarge the public’s retirement-savings shortfall. The $2.2 trillion CARES Act has made it easier for workers with 401(k) retirement plans to gain access to that money before they retire. It eliminated tax penalties for early withdrawal, raised the amount that could be withdrawn and allowed several years to pay taxes on withdrawals or to put the money back into the plan.

Deborah Lucas, professor of finance at MIT’s Sloan School of Management and the Director of the MIT Golub Center for Finance and Policy, thinks the relaxed rules are a good thing. “It has bothered me that retirement funds are put into the category that you can only get at them in an emergency,” she says.

But how will people tapping their 401(k)s early fare when they are actually in retirement and some of their savings has dissipated?

Helping Americans Handle Financial Emergencies

A better idea, some say, is for Congress to make it easier for employers to offer workplace-sponsored emergency savings plans that could be tapped at any time for any reason. This way, retirement accounts would be viewed as…retirement accounts.

“Maybe [now], employers will help with emergency savings. People will see more merit to that than before.” says Neil Lloyd, partner and head of U.S. Defined Contribution & Financial Wellness Research at Mercer, a human-resources consulting firm.

With only half of American workers even allowed to put money into a 401(k) or similar retirement plan at work, and employees of small businesses especially left out in the cold, the pandemic has shown the urgent need to bring more private-sector workers into the retirement savings system.

But efforts at the federal level to offer some kind of universal IRA or 401(k) have gone nowhere. Several states, however, have stepped into the breech with their own state-sponsored IRAs.

“There is a big chunk of people who don’t have access to retirement plans,” says Bruce Wolfe, head of Individual Retirement Strategy at Insight Investments, a global asset manager. “We need to focus on expanding access to more people.”

Here’s the thing: Reforms like these have been repeatedly called for over the years. Alarms have been sounded well before COVID-19 that the financial prospects of future generations of retirees have been dismal. The pandemic, however, has upped the odds that too many older workers will face hardscrabble times late in life.