Peaceful Visits With My Brother

Recalling quiet walks and shared meals with an older sibling who had dementia

"It's peaceful here, calm," he’d say. "I have my books. I read the newspaper and listen to the radio. Of course, the news is no good. People are devising bigger and better ways to kill each other every day." He’d sigh.

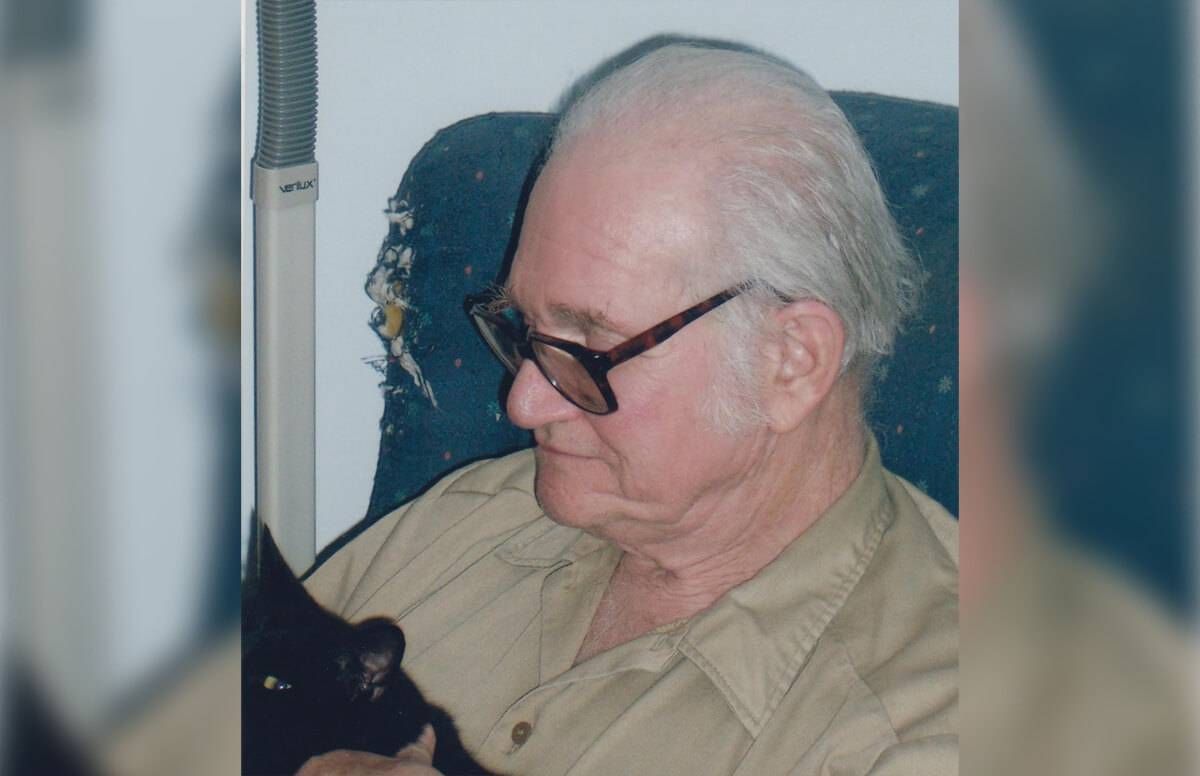

We would sit facing each other in his living room, at his home in Beverly, Mass., my older brother and I. His fingers would beat a steady and rhythmic tattoo on the cat-clawed, tattered arms of the easy chair. In a way, he was no different than he was the year before, or the year before that. Not much different, at least in my mind, than he had been most of his life — eccentric is all — just maybe more so.

My brother’s name is Doran. It’s a combination of our mother’s and father’s names — Isadore and Annette. It was an embarrassment to my brother. He had many bad experiences because of it. Maybe the worst was when he was a senior at the Bronx High School of Science. I guess the school got notifications of college admissions and announced them at the morning assembly.

“Will Miss Doran Koulack please stand up?” the woman said as a prelude to announcing that he had been admitted to Harvard. He told me later that he almost didn’t stand and how mortified he had been when the entire audience (including, of course, those who knew him) burst into laughter rather than applause for his accomplishment.

But some time ago his somewhat peculiar behavior — nothing to make a federal case about, just things like putting his soiled dishes in the cupboard or wearing hats one on top of another in the house — led to a round of visits to doctors and ultimately the diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

I looked it up. The frontal and temporal lobes of my brother’s brain were shrinking. They are the regions of the brain that are responsible for one’s personality. They serve a sort of executive function, directing one’s social behavior — make it one hat instead of several, or maybe none at all, at least in the house.

Out for a Walk

Often when I would visit my brother, I would try to get him to go out for a walk. “You need the exercise,” I would tell him.

“I get plenty of exercise,” he’d say.

I'd wait and then he'd add, “I make myself get up from the chair and I walk over there.” He’d point to the far corner of the room. “And back,” he. "Or sometimes I walk all the way to the kitchen and force myself to eat something.”

“Well, do it for me,” I’d say. “I need the exercise and I’d like your company.”

Then my brother would sigh and nod and struggle out of his chair. I’d help him down the front steps of the house and we would slowly walk along the street and through the gate of the nearby cemetery.

“You know, people are dying to get in here,” he’d tell me, a sly grin crossing his face.

We’d find a bench and sit in silence, gaze at the array of crosses and monuments, watch the seagulls circling overhead and observe the occasional mourners as they placed flowers on the gravesites of loved ones. I’d sense my brother stirring — impatient to resume our stroll.

“Should we walk some more?” I’d ask.

“No, let’s go home,” he’d say. “It must be supper time.”

We’d retrace our steps, walking in silence. Occasionally he’d stop to rest on a stoop of one of the houses along the way.

Listening to My Brother's Stories

Once back home, I would help him off with his jacket and ask him if he needed to wash his hands.

“No, I’m clean,” he’d tell me, “She gave me a shower.” The “she” being the caregiver who comes to bathe him and change his clothes a couple of times a week to help his wife, Jean, who was ill at the time. “Let’s go and eat.”

We'd sit down at the table, across from one another. “You know, I really have no appetite,” my brother would say, “I have to force myself to eat to keep my weight up to maintain my balance when I walk.”

But the truth was that he’d grown to be enormous. And at the dinner table, seated on his special cushions, he'd concentrates on his food and eat with gusto.

Occasionally he’d look up, pleased with a thought. “If you’re a schmoo, can you write a haiku?” he’d ask. And then it’s likely to be a stream of homonyms: “Yesterday I bawled because I’m bald. Is it possible for a baron to be barren? How many aunts does an ant have?” His eyes would twinkle and then he would smile before falling silent.

After supper, we'd return to our chairs in the living room, sit across from each other and I'd listen to my brother reminisce. He’d tell stories — of failure and regret mostly, but some of unexpected triumph. His voice would be flat, emotionless. Was that the disease, I’d wonder?

'It's Very Peaceful Here'

And then it would be time for me to go to bed, although my brother would be staying up into the wee hours of the morning. As I’d get up from my chair, he’d start organizing himself, getting ready for his vigil.

“Goodnight, honey,” he’d say. “It’s very peaceful here. I have the newspaper and my books and I can listen to the radio.”

And when he was in the hospital, in January, 2015, just before he died, he reassured me again as I sat beside his bed.

“It’s very peaceful here,” is what he told me.