Problems of Aging Your Mother Didn’t Tell You About

How one woman's understanding about aging is tangled in other emotions

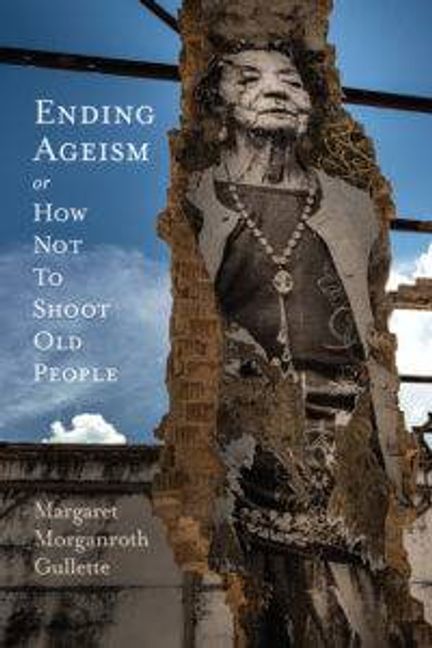

Editor's Note: This essay has been adapted from the author's book, Ending Ageism, or How Not to Shoot Old People, released by Rutgers University Press in August.

My mother didn’t tell me about “aging” because it just wasn’t done. (She lived long enough to be expected to know: She died at 96, and in 2010.) A good mother lives humorously with whatever comes up and shares tips about the tastiest cracker brands and sends a daughter the designer clothes that don't suit her anymore.

Anyway, I knew her life as it unfolded because we talked on the phone. She walked a mile a day in her 80s and lived off and on with a lover who had panic attacks and left the apartment with almost no warning, suitcase in hand. She had cataract operations. She broke a hip running to catch a plane. She ran a beneficent nonprofit that arranged to take people to the theater and concerts rather than complaining that South Florida was a cultural wasteland. And what is old age but just more living?

On her birthday, when I congratulated her perhaps too heartily, she once said, “A year older. One year less.” Which, think about it, is the statement of someone who likes her life.

My mother would not have believed that the news could be full of commentary about “aging:” How to prevent it, how to avoid it, how to do it gracefully or positively or whatever the gerontological term of art happens to be. Aging has been made mysterious and separate, as if it were a secret Kingdom that someone somewhere must have the precious Key to. As an age critic and a human being, I resist that.

Here I am, her daughter, always (in her later years) happily following in her footsteps, nevertheless ready in the 21st century to trot out a few perceptions of this most mysterious stage of life. The main mistake advice-givers make is to claim that every experience of aging-toward-old age is the same for one person as another. That can’t be true.

But neither is any event unique. So here is one brief, first-hand interim report from one woman who lives in our era of nonstop focus on “aging,” about one neglected aspect of life. This caught my attention: Recklessness.

Goodbye to Recklessness

If you think that recklessness is that teen thing, or, for those who missed it then out of caution, a 30s thing, or a midlife-crisis thing, think again. Forms of recklessness differ: Some people ride motorcycles, smoke, sleep with their best friend’s husband. Whatever it is you do against your will and common sense, it is unlikely to change as you age. You have a character, and this you will — in the main (depending on your degree of pig-headedness or some say strength of character) — live up to, to the very end. Some will go on repeating this pattern just to deny that they are “aging.”

But better counsels may ultimately prevail. And this it seems is happening to me.

The first phase: In my character, summer ladder-climbing was entrenched like cold lemonade or painting my toenails before July Fourth. When we planted a capitata yew hedge along the property line in 1974, I promised the neighbors on the south side that I would prune it. I even wrote it into the contract we signed, unasked. And I did it faithfully, for decades. I have a ladder with arms that sinks itself into the hedge, I wear proper sneakers, I have sharp shears.

What I had ignored was that the yew got taller every year — not much, because the point of pruning them was to keep them lower than they wanted to be. Still, natural growth can’t be stopped, and the capitate aims for 50 feet and maturity. They are certainly trying to be mature. This is when recklessness came into it. I persisted. I enjoyed the climb up each tree, the muscular strength that squeezing the shears gave to my upper arms, the sweat tears in my eyes, the embrace of the tree-everything!

Loss of Interest and Increase of Fear (or Am I Aging?)

The second phase: Losing interest. At the same time as the hedge was getting bigger naturally, I was also progressively losing interest in pruning it. Didn’t I enjoy the climb up each tree — eight, 10, 12 feet off the ground, and beyond? At a certain point, I said, “I’ll do only one a day.” And later, “Only in the late afternoon.” Later yet, more grimly, “No more sweat.” Every year I put it off ‘til later in the summer. It was irksome, facing south, to have the midsummer sun in my eyes. My muscles were up to it. It just was not fun. Was that no-longer-fun feeling aging? Is it obligatory to call it aging?

Over the same period, the ladder became, as of course it had always been, a fearful object. It had to be moved from tree to tree, carefully, so as not to crush flowering plants or tip sideways. Its arms no longer had much to embrace at the spindly tops of the yew trees. If I bent out with my shears too far to the side, the ladder wavered. Fear and loss of interest seemed to coincide. Was this the aging part?

That is the core question. Can we refuse to ascribe change unilaterally to weakness and decline? In other words, when unusual things happen, can they not be set down to “aging?” Can they partly be ascribed to fatigue or boredom? Could the whole conversation be more interesting, for heaven sake?

It seemed wise to be more fearful of falling. You don’t have to read the public-health surveys of older people who fall to know that being laid up with a broken limb is an unpleasant interruption of life, even at 40. But I hadn’t yet taken this view seriously. This is the moment when I broke with my own recklessness.

Is this, then the wisdom of aging, to learn what you have long known but recked not?

The third phase: For the first time in your life, if you personally give up something that must still get done, you discover you now have to find good help when you need it.