Remembering Woodstock 50 Years Later

As a young reporter, author Sara Davidson soaked in the vibe of the 'New Dawn'

“There we were all in one place/A generation lost in space ...” Don McLean, “American Pie”

“Judy Blue Eyes,” “Somebody to Love,” “With a Little Help from my Friends"— I’ve been singing these and other late-1960s songs over and over, to memorize the harmonies for a concert our vocal group is giving to celebrate the 50 anniversary of Woodstock. (Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation will premiere on PBS on Tuesday, August 6 at 9 pm/8 pm CT.)

I’m the only one in the group who was actually there. In 1969, I was a young reporter living in New York, covering the city for The Boston Globe. My husband was a disc jockey on the primo FM rock station in the city. They’d been running ads for a three-day August festival of peace and music in Bethel, N.Y., 43 miles from Woodstock, the town where Bob Dylan, The Band and lots of musicians were living.

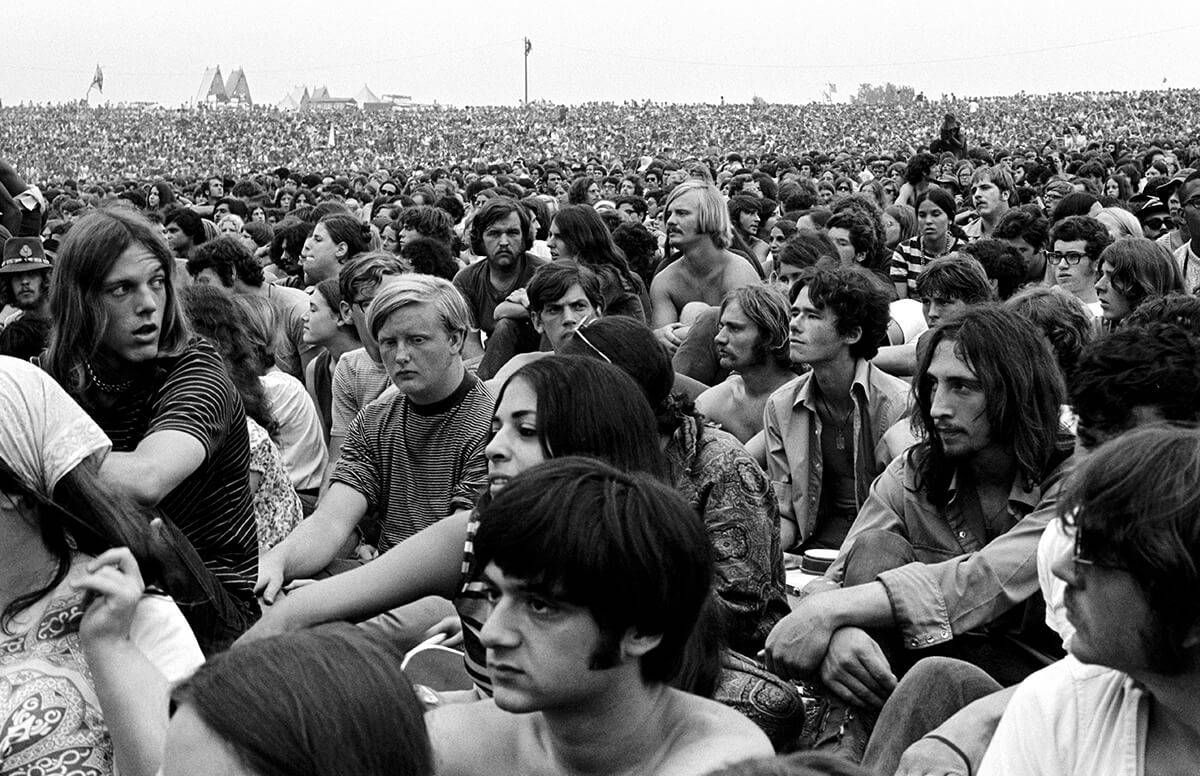

The largest football stadiums in America hold about 100,000. Woodstock had five times that many [people].

There had already been other music festivals that year. The Atlantic City Pop Festival, two weeks before Woodstock, featured many of the same musicians and drew about 70,000 people. Other festivals took place in Georgia, Wisconsin, Denver and Seattle. But unlike the others, Woodstock would have no assigned seats, no lodging. People would “camp out on the land.”

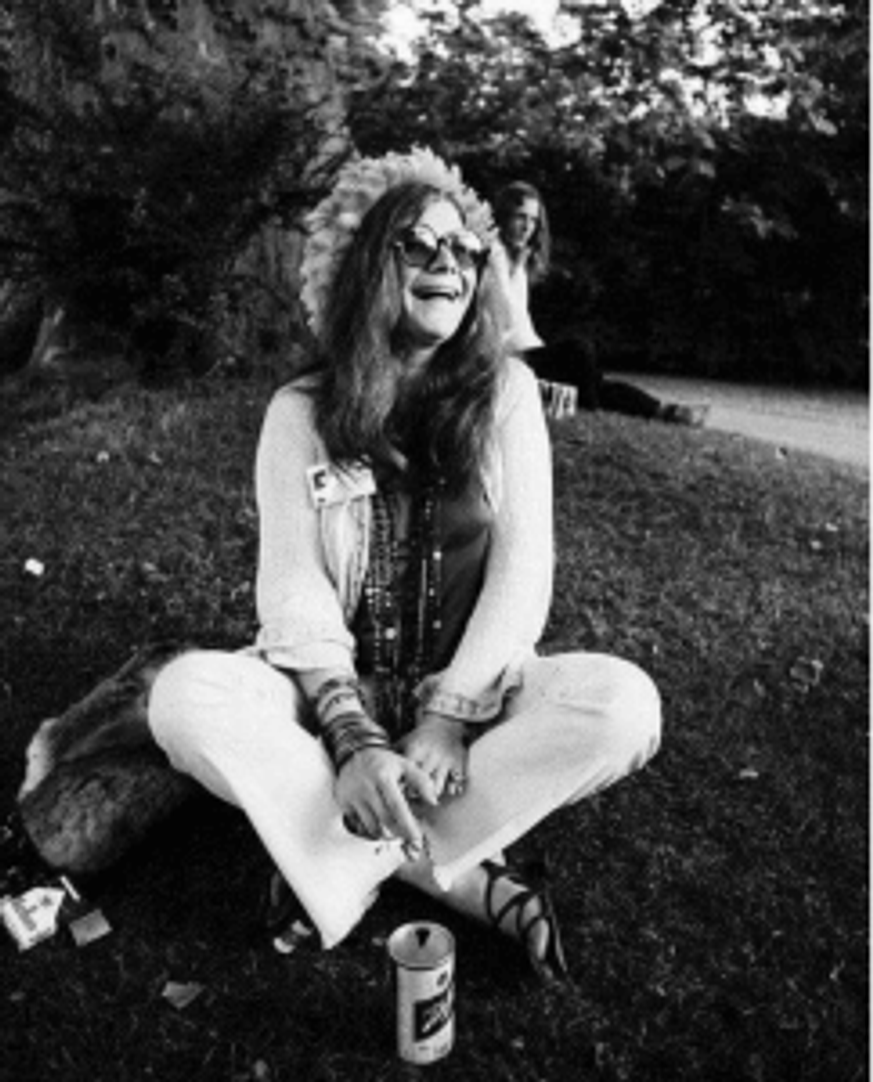

Janis, Grace and The Grateful Dead

No one expected this festival would be a big deal. Then, things changed.

The Friday that Woodstock began, we were hosting a dinner party, and at 9 p.m., I got a call from Myra Friedman, who did publicity for Janis Joplin and The Band, and was at Woodstock with them.

“You’ve got to get up here!” she shouted. “It’s fantastic. There’s half a million kids here! Never seen anything like it.”

How could I get there? We’d heard that all the roads leading to the festival were blocked, with kids abandoning their cars to hike 10 or 15 miles to the site, carrying sleeping bags, guitars and food.

Myra said, “You can drive to Liberty — that road is clear. Come to the Holiday Inn, where all the performers are staying, and we’ll get you over to the festival.”

At 8 the next morning, I jumped in my black VW Beetle, picked up my friend, Kathy Wenning, and drove up the expressway to the Holiday Inn in Liberty. So far, so good. In the bar, I saw Janis Joplin, wearing a purple shirt and black satin pants, drinking Southern Comfort and yelling “Hiya honey" to everyone.

In the café, Grace Slick was having breakfast at 2 p.m. with The Grateful Dead. Joe Cocker was wandering around in a tie-dyed shirt and wild hair.

Nothing was happening on schedule.

Traveling by Caravan

The motel was 20 miles from the festival site, a grassy crater on Max Yasgur’s dairy farm. The organizers had hired limos to shuttle performers to the site, but the limos couldn’t get there. All roads in the area were jammed with cars parked helter-skelter, as if they’d been dropped from the sky by a salt shaker.

The organizers brought in a helicopter, but it could only carry five people at a time. By Saturday, though, they’d devised a system: several times a day, they’d form a caravan of limos with police escorts and break trails to get through to the site.

When the next caravan formed, Myra jumped in my Beetle and we cut into the middle of the limo line. If anyone waved or shouted at us to get away, Myra yelled back at them.

We took off with sirens blaring and red lights flashing. It was comical: police car, limo, limo, small black Beetle, limo, limo. We drove across fields, over dirt roads and private driveways, and then we had to drive through the masses of people crushed together in the open crater. The crowds parted like The Red Sea, but I was terrified I’d hit someone.

'We Must Be in Heaven, Man!'

We arrived backstage — a roped-off area behind the speakers — that was an oasis. There were picnic tables, cooks preparing meals and a dozen canvas teepees with futons and pillows inside.

I sat down not far from Joan Baez, who, to my shock, had cut her trademark long black hair to just below the ears. Her husband David Harris was in jail for refusing the draft, and she was six months pregnant.

Because I was writing a story on the festival, I left Kathy backstage to go out among the crowd.

It’s hard to really grasp the size of it. The largest football stadiums in America hold about 100,000. Woodstock had five times that many [people].

Kids had started arriving the week before, and by Friday, they’d trampled down the cyclone fences, so it became a free event.

Close to the stage, they were packed so tightly you had to push hard to make your way through human walls. As you moved farther back from the stage, the crowd began to thin, and at the very back, there were campsites, tents and psychedelic buses. The Hog Farm Commune from New Mexico had set up a soup kitchen where they offered free food. The peace activist and Woodstock emcee Wavy Gravy, head of The Hog Farm, said, “We’re all feeding each other. We must be in heaven, man!”

The crater had turned into a city made up entirely of youths. Swarms of 15-year-olds had hitchhiked there, and young couples with babies formed their own little neighborhood.

No one was in charge; it was an outlaw gulch. They could smoke or ingest anything they wanted, take off their clothes, swim naked and… whatever.

A Collective High

Shortly after dark on Friday, a volunteer took the stage and said, “The organizers didn’t plan for this many people! We have shortages of food, water and latrines. So it’s up to us. Look around — the people around you are your brothers and sisters. Treat every person here like they really are your brothers and sisters. Share, take care of each other. That’s the way we’ll get through this.”

A medical tent was set up with volunteer doctors. Kids freaking out on acid would come in yelling, “I’ve been poisoned!” and other kids would talk them down. When they recovered, they were asked to stay and do the same for the next ones freaking out.

Dr. William Abruzzi, the medical director, said at the end of the festival that his staff did not treat “one single knife wound or black eye or laceration that was inflicted by another human being.” No one saw a single fight.

Nature, however, did not cooperate. There was lightning that threatened the electrical equipment and two torrential rainstorms, which turned the crater into a sea of mud. But most of the people rolled with it. They took off their wet clothes and washed themselves off in the lake.

I suspect that one of the reasons for the collective high — the shared sense of joy and generosity — was that the drug of choice was marijuana, not alcohol. A local farmer said, “If marijuana makes people this gentle, it should be distributed free by the government.”

There was no tension with police. Arlo Guthrie said he’d enjoyed “rappin’ with the fuzz,” and the county sheriff, Louis Ratner, said, “I never met a nicer bunch of kids in my life. When our cars got stuck in the mud, they helped push us out. I think a lot of police here are looking at their attitudes.”

'This Is the New Dawn'

On the stage Saturday night, a stellar lineup of heavy bands followed one another: Canned Heat, Santana, The Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Sly and the Family Stone, The Who, Jefferson Airplane.

But the performance that’s fixed in my mind, 50 years on and still vivid, is Janis Joplin, at three in the morning, singing, “Ball and Chain.” It was as if she was wringing her soul inside out, whispering, yelling, whipping her hair from side to side, climbing up and down the scales, crying, shaking as if having convulsions. She gave everything she had until she was spent. (It’s about 30 minutes into the Woodstock YouTube video.)

I crawled into one of the teepees and collapsed. When I awoke, the sun was up and Grace Slick, dressed all in white with fringes from her shoulders to her toes, was greeting the crowd, saying, “This is maniac morning music. Believe me: This is the New Dawn!”

(Part 2 of this essay, “The Children of Mainstream America,” can be found at Sara Davidson’s website on her blog.)