These Retirees Are Pushing to Save Their Pensions

Will their efforts preserve their promised retirement benefits?

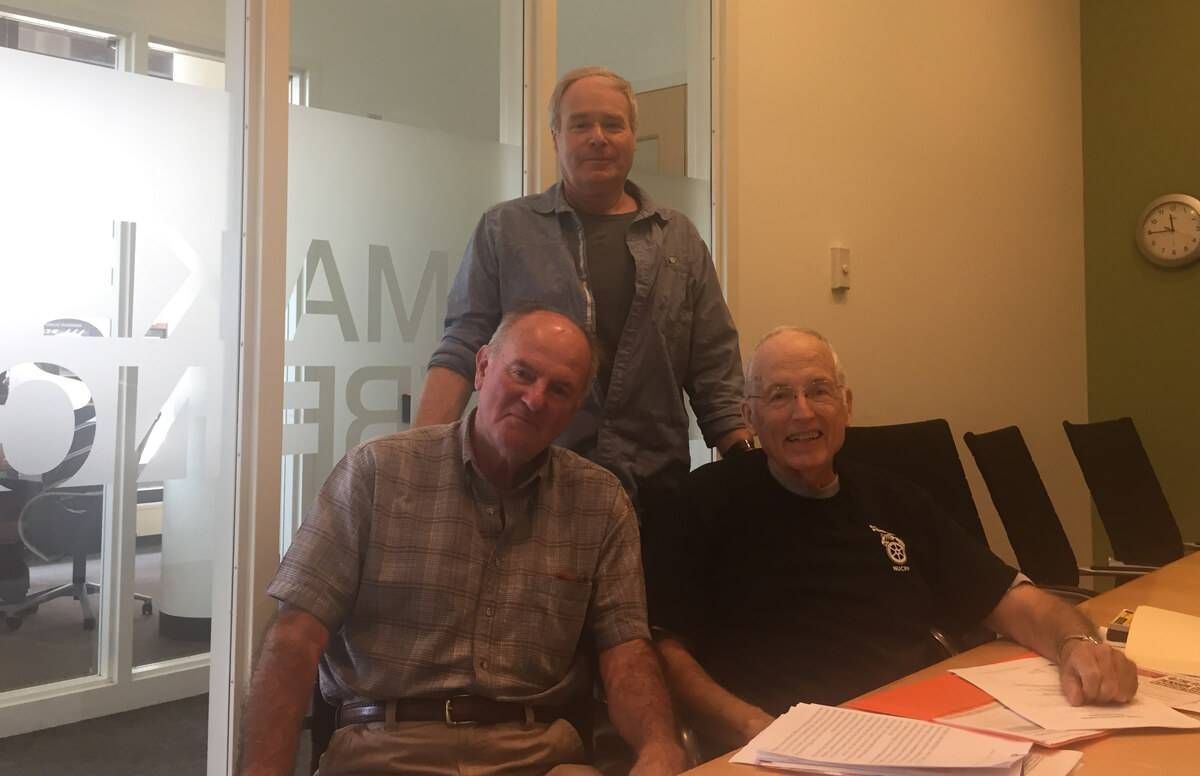

Let me tell you about three long-time truck drivers and Teamsters who I met recently. They have a sad and interesting tale I think you’ll want to know if you’ll be retiring soon or are already retired.

Bob McNattin, now 80, lost his job and his house during the Great Recession. So at 73, he headed to North Dakota to drive a truck, working 80 hours a week. At 78, he moved back to the Twin Cities and now delivers motor homes. Ex-trucker Jeff Brooks, 67, currently has a part-time gig. And Steve Baribeau, also 67, retired due to a disability, but figures he’ll need to get a job soon, since his wife is retiring and losing her employer-sponsored health insurance.

McNattin, Brooks and Baribeau — and some 400,000 other Teamsters — could end up collecting a small fraction of their pensions without federal help. The three road warriors are working together furiously to stave off threatened cuts in their retirement income due to shaky promises made by the financially troubled Central States, Southeast and Southwest Areas Pension Fund, predicted to run out money in 2025. “We had to do something,” says Brooks.

(Financial shortfalls seem endemic in many parts of America’s frayed retirement savings system as PBS FRONTLINE recently showed in its excellent documentary about underfunded public pensions, The Pension Gamble.)

Defend Our Pensions-Minnesota

The trio first got together, along with several other Teamsters, in a coffee shop in St. Paul, Minn. in 2014. They each put $20 into the kitty and started a grassroots effort called Defend Our Pensions-Minnesota. The organization works with similar groups in other states, including mine workers and iron workers also worried about losing their promised pensions. They’ve held rallies in Minnesota and joined demonstrations in Ohio and elsewhere.

In July 2017, they were part of a 30-member delegation that met with U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin to make the case for the government to step in and protect troubled pensions. (They never heard from Mnuchin again.)

The most recent meeting of Defend Our Pensions-Minnesota had more than 1,000 retirees attending. The efforts of McNattin and Brooks to maintain retiree financial security were recently recognized by AARP Minnesota and the nonprofit organization Pollen in their 2018 "50 Over 50" list, recognizing 50 Minnesotans over 50 who are making a difference.

“I never thought at this stage of life I’d be doing something this consequential and being with so many wonderful people,” says McNattin.

How This Pension Problem Happened

Here’s the background: The mostly unionized truck drivers, miners, iron workers, carpenters and other skilled laborers that built the economy after WWII moved from job to job plying their trade with different employers, often small-to medium-sized companies. The workers never stayed long enough with one firm to qualify for a traditional, defined benefit pension plan, the kind that pays a lifetime monthly income in retirement. So a single union (think Teamsters and United Mine Workers) would negotiate with multiple employers and establish a multiemployer pension plan funded by employers and union members. There are over 1,200 multiemployer pensions covering about 10 million workers.

The rub? More than 100 of these plans, covering over one million participants, lack sufficient funds to meet promised benefits in full. Central States pension, set up in 1955, is the largest of them. The Society of Actuaries examined 115 underfunded multiemployer plans, concluding that even with “extraordinarily optimistic investment returns,” 68 of them would be insolvent within 20 years. (By contrast, concerns about single-employer pensions are mostly concentrated among bankrupt companies like Sears Holding Corp. )

When a pension fund runs out of money, retiree benefits are cut. And the actuaries say the benefit cuts for those 68 pension funds could range from less than 20 percent to more than 90 percent.

Central States’ shortfall dates to the brutal price war triggered by trucking industry deregulation in the early 1980s. Thousands of unionized companies failed. New companies rushed into the business, but their workers usually didn’t belong to a union. The cumulative effect of failing employers and falling union membership was disastrous.

Will the Federal Government Come to the Rescue?

Compounding the Teamsters’ worry are predictions that the federal government’s Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) multiemployer insurance program — a backstop against bankruptcies — won’t have any money on hand by the end of fiscal year 2025. The PBGC guarantees a minimum payout to beneficiaries if a plan it insures fails.

Here’s an exchange last May between Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) and Thomas Reeder, executive director of the PBGC, during a hearing to come up with solutions for financially strained multiemployer pensions:

Brown: “The minimum guaranteed benefit the PBGC pays to retirees if a plan fails is already much lower than the retirement these workers earned, that they bargained for and gave up pay raises for — that they budgeted for when taking out mortgages, and that they count on to pay their bills. Absent Congressional action, would the PBGC even be able pay that minimum guarantee?”

Reeder: “No. We would be cut to about 1/8th about what the minimum benefit is –“

Brown: “Talk more about that, so the minimum benefit which would be markedly less than what they were promised, what they negotiated, what they were getting, what they thought they were getting. That minimum benefit is already small, relatively, you’d be force to cut the average benefit how much?”

Reeder: “If they’re making $8,000 in guaranteed benefits today, they’d get less than $1,000. I’m talking about an annual number.”

Brown: “So it would be cut to 1/8th perhaps.”

Reeder: “Or less.”

Imagine working 30 or 40 years only to learn that your promised pension payout will plummet just when you need the money. “This has been our careers,” says McNattin.

A New Law and a Proposal

To deal with these pensions’ woes, The Multiemployer Pension Reform Act of 2014 allowed multiemployer plans to propose cuts to accrued benefits. Central States leadership then designed a plan to reduce benefits by 34 percent, on average. The prospect galvanized opposition among Teamster retirees, and in 2016, the U.S. Treasury rejected the proposal. In essence, the cuts were deemed insufficient to the problem and too poorly communicated to the average participant.

So now, Defend Our Pensions-Minnesota and other organizations are pushing for a new legislative solution. Their favored approach is for Congress to embrace the Butch Lewis Act. (Lewis was a Teamster, truck driver and leader in the pension protection movement who died in 2015.)

Under this bill, plans like Central States would receive low-interest, long-term loans from the U.S. Treasury to close the underfunding gap and maintain retiree benefits. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the Act would cost some $34 billion over the 2019 to 2028 period.

Not that many years ago, Washington leaders would have stepped forward and negotiated a bipartisan resolution to the multiemployer pension problem. They would’ve agreed that it wasn’t right for older workers to suffer in retirement due to no fault of their own. But those days are well past. Conservative opposition in Washington has stymied any action on the Butch Lewis Act or anything like it.

“Our future is in Congress’ hands,” says Baribeau.

How to Help Blue-Collar Workers

In the run-up to the mid-term elections, political candidates profess their love of blue-collar workers. Elite media commentators and Silicon Valley plutocrats proudly announce trips out of their exclusive enclaves to visit and listen to “real” Americans. But if people really want to improve the lives of America’s laborers — especially older retirees — how about fighting to preserve the pensions they earned over careers mining coal, driving freight trucks and pounding nails?

They earned the benefit. They should know their retirement income is secure. As McNattin says: “I want to spend more time with my grandchildren.”

Will he be able to?

Several Other Major Multiemployer Pension Plans in Trouble

- Automotive Industries: Due to a decline in automotive industry businesses in the San Francisco Bay Area and economic recessions

- Bricklayers Local 7: Experiencing increased member attrition to nearby unions, which maintain plans that are better funded

- Ironworkers Local 16: Due to economic decline, a loss of qualified workers because of fewer opportunities and stagnant wages, and a dramatic drop in employers

- United Furniture Workers: Rapid increase in U.S. furniture imports since the 1970s put increasing pressure on U.S. furniture manufacturers and the pension plan

Source: Testimony of Todd Goldman, Academy of Actuaries, Joint Select Committee on Solvency of Multiemployer Pension Plans Hearing, April 18, 2018