Revisiting My Caretaking Diary

What surprised me in reading my day-to-day account of my wife's cancer ordeal was just how truly awful it really was

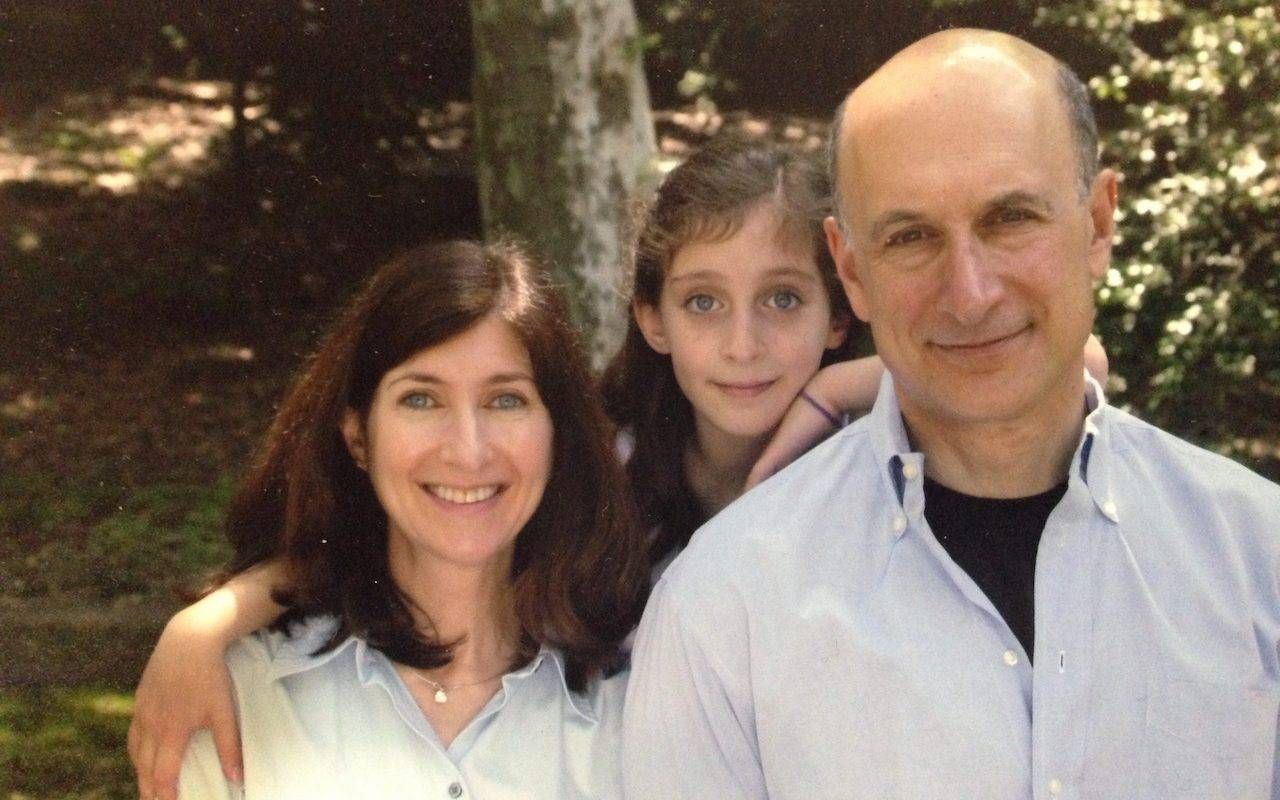

Shortly after my wife Lisa passed away, I ran into a neighbor who lost her husband ten years earlier. Although we were both widowed, the circumstances were very different. My wife died after a very difficult and long (4 year) bout with cancer. Her husband died instantly from a heart attack.

We asked each other the obvious question: Is it better to lose someone quickly, so they don't have to go through prolonged suffering … or is it better to have the opportunity to be with them longer, prepare for the inevitable and say the things one needs to say, even though we must watch them in pain? After weighing the pros and cons, we came to the conclusion that they both stink.

I realized I was just trying to get through each day. There wasn't an ounce of extra strength to think about the present, the future or anything else.

I didn't really think about that question for five years after my wife's death because I blocked out the memory of those long days and nights of sickness. It took me five years to go back to my diary and remember what that time was like.

The Moments I Remember

What surprised me in reading my day-to-day account of the ordeal was just how truly awful it really was. Between the long hospital stays, the endless talks with doctors, the nurses, the constant tests, my wife's physical discomfort and mental strain and at the same time, taking care of our daughter and handling my job, I realized I was just trying to get through each day. There wasn't an ounce of extra strength to think about the present, the future or anything else.

Here are the moments I remember: Long days that went into nights, sitting beside her in her hospital room. When I finally left at around ten or eleven, I noticed the nurses at the desk staring at me with a look of concern. I have no idea what my own face conveyed. One of the nurses would often ask how I was and reminded me to get something to eat. I always answered with a "thank you" and a forced smile.

But when I left the hospital and walked out the front entrance, I distinctly remember the great relief of breathing in the outside air – taking it in with large gulps. In winter or fall, summer or spring, it didn't matter (and it happened through all the seasons). I left the stale air and the beeping machines of the hospital room and just reveled in the fresh, outside air. And with that, came the guilt that I could escape this prison for a few hours, but my wife was stuck there. There was also the question: why was she the sick one and why was I absolutely fine?

There were days I was frustrated and angry and tried hard not to let it show, but I don't think I always succeeded.

There were days when she was discharged for brief periods, and I took care of her at home. I would try to have food in the house that might tempt her, but I never seemed to succeed. When I finally sat down to just read something or close my eyes, inevitably she would need something. Sometimes I would have to run to take care of our daughter who was still in high school. But, for the most part, this 16-year-old was overlooked during this time.

I was lucky to have the world's kindest and most considerate boss, who let me work remotely so I could be with my wife. I realized even then how fortunate I was. If I still worked for the large corporation where I began my career, I would have lost my job and with it, our medical insurance. Or I would not have been with her for the last three years of her life.

There were days I was frustrated and angry and tried hard not to let it show, but I don't think I always succeeded. There were times I resented my friends who seemed to be swimming through life without a worry. I could be short tempered — even more than usual.

One night, I came home and opened a can of beer. Then another … and another. Even in college, I rarely had more than two beers, never more than three. The next morning, I counted almost 12 empty cans strewn around the kitchen.

But for the most part, I knew that every moment with her was precious and there would be a time when she would no longer be with me — something I could not fathom. Some days, I imagined I would be a caregiver for the rest of my life.

When you are with someone who is dying, you worry, you try to offer comfort, but you don't really understand where all of this is heading.

Looking at a future without her reminded me of trying to grasp the concept of infinity as a child. I could just go so far and then I stopped because I didn't have the bandwidth. When you are with someone who is dying, you worry, you try to offer comfort, but you don't really understand where all of this is heading. It's just one big mystery.

We Had a Little More Time

A brilliant rabbi once told me something that has always stayed with me. "We are mortals," he said. "We are not supposed to understand what happens or where we go. Perhaps somewhere down the road we will, but not in this lifetime."

That actually gives me comfort.

In the end, as difficult as that time was – and it was so difficult – I am surprised to admit that I now miss those long days and nights. As hard as they were, she was still here with me. I could still be with her and converse with her. Now, there is nothing but a great big void. Yes, I now have all the time in the world to do whatever I please, but her absence makes that time less compelling.

So, if I had that conversation now with my neighbor who lost her husband so suddenly, I would tell her that I consider myself the lucky one. I … we … had the most precious gift in spite of everything that happened.

We had a little more time.