The Secret of Aging and How to Slow It Down

'The Telomere Effect' authors say the key is changing how we live and handle stress

What makes some people age more quickly than others? What exactly is aging? And can we do anything about the speed at which we grow old? Authors Elizabeth Blackburn, a molecular biologist, and Elissa Epel, a health psychologist, offer answers in a fascinating book, The Telomere Effect: A Revolutionary Approach to Living Younger, Healthier, Longer.

In 2009, Blackburn was one of three scientists awarded the Nobel Prize for their research on telomeres (protective DNA at the ends of chromosomes) and how they protect chromosomes. Epel, one of the 2016 Next Avenue Influencers in Aging, studies how chronic stress accelerates aging, with a focus on telomeres. Both authors work at the University of California, San Francisco.

The following is excerpted from The Telomere Effect by Elizabeth Blackburn, Ph.D. and Elissa Epel, Ph.D. Copyright (c) 2017 by Elizabeth Blackburn and Elissa Epel. Used by permission of Grand Central Publishing. All rights reserved.

It is a chilly Saturday morning in San Francisco. Two women sit at an outdoor café, sipping hot coffee. For these two friends, this is their time away from home, family, work, and to-do lists that never seem to get any shorter.

Kara is talking about how tired she is. How tired she always is. It doesn’t help that she catches every cold that goes around the office, nor that those colds inevitably turn into miserable sinus infections. Or that her ex-husband keeps “forgetting” when it’s his turn to pick up the children. Or that her bad-tempered boss at the investment firm scolds her — right in front of her staff. And sometimes, as she lies down in bed at night, Kara’s heart gallops out of control. The sensation lasts for just a few seconds, but Kara stays awake long after it passes, worrying. Maybe it’s just the stress, she tells herself. I’m too young to have a heart problem. Aren’t I?

“It’s not fair,” she sighs to Lisa. “We’re the same age, but I look older.”

Two Faces of Age

She’s right. In the morning light, Kara looks haggard. When she reaches for her coffee cup, she moves gingerly, as if her neck and shoulders hurt.

But Lisa looks vibrant. Her eyes and skin are bright; this is a woman with more than enough energy for the day’s activities. She feels good, too. Actually, Lisa doesn’t think very much about her age, except to be thankful that she’s wiser about life than she used to be.

Looking at Kara and Lisa side by side, you would think that Lisa really is younger than her friend. If you could peer under their skin, you’d see that in some ways, this gap is even wider than it seems. Chronologically, the two women are the same age. Biologically, Kara is decades older.

Does Lisa have a secret — expensive facial creams? Laser treatments at the dermatologist’s office? Good genes? A life that has been free of the difficulties her friend seems to face year after year?

Not even close. Lisa has more than enough stresses of her own. She lost her husband two years ago in a car accident; now, like Kara, she is a single mother. Money is tight, and the tech start-up company she works for always seems to be one quarterly report away from running out of capital.

What’s going on? Why are these two women aging in such different ways?

The answer is simple, and it has to do with the activity inside each woman’s cells. Kara’s cells are prematurely aging. She looks older than she is, and she is on a headlong path toward age-related diseases and disorders. Lisa’s cells are renewing themselves. She is living younger.

Why Do People Age Differently?

Why do people age at different rates? Why are some people whip smart and energetic into old age, while other people seem much younger and are sick, exhausted, and foggy? You can think of the difference visually:

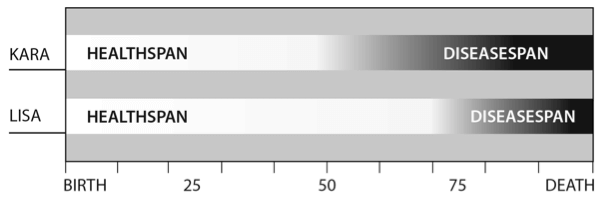

Our healthspan is the number of years of our healthy life. Our diseasespan is the years we live with noticeable disease that interferes with our quality of living. Lisa and Kara may both live to 100, but each has a dramatically different quality of life in the second half of her life.

Look at the first white bar above. It shows Kara’s healthspan, the time of her life when she’s healthy and free of disease. But in her early 50s, the white goes gray, and at 70, black. She enters a different phase: the diseasespan.

What Is the Diseasespan?

These are years marked by the diseases of aging: cardiovascular disease, arthritis, a weakened immune system, diabetes, cancer, lung disease and more. Skin and hair become older looking, too. Worse, it’s not as if you get just one disease of aging and then stop there. In a phenomenon with the gloomy name multi-morbidity, these diseases tend to come in clusters. So Kara doesn’t just have a rundown immune system; she also has joint pain and early signs of heart disease. For some people, the diseases of aging hasten the end of life. For others, life goes on, but it’s a life with less spark, less zip. The years are increasingly marred by sickness, fatigue and discomfort.

At 50, Kara should be brimming with good health. But the graph shows that at this young age, she is creeping into the diseasespan. Kara might put it more bluntly: she is getting old.

Lengthening the Healthspan

Lisa is another story.

At age 50, Lisa is still enjoying excellent health. She gets older as the years pass, but she luxuriates in the healthspan for a nice, long time. It isn’t until she’s well into her 80s — roughly the age that gerontologists call “old old” — that it gets significantly harder for her to keep up with life as she’s always known it. Lisa has a diseasespan, but it’s compressed into just a few years toward the end of a long, productive life. Lisa and Kara aren’t real people — we’ve made them up to demonstrate a point — but their stories highlight questions that are genuine.

How can one person bask in the sunshine of good health, while the other suffers in the shadow of the diseasespan? Can you choose which experience happens to you?

The terms healthspan and diseasespan are new, but the basic question is not. Why do people age differently? People have been asking this question for millennia, probably since we were first able to count the years and compare ourselves to our neighbors.

At one extreme, some people feel that the aging process is determined by nature. It’s out of our hands.

Today there are plenty of people who feel that nurture is more important than nature — that it’s not what you’re born with, it’s your health habits that really count.

The Significance of Telomeres on Aging

We’re going to show you a completely different way of thinking about your health. We are going to take your health down to the cellular level, to show you what premature cellular aging looks like and what kind of havoc it wreaks on your body — and we’ll also show you not only how to avoid it but also how to reverse it. We’ll dive deep into the genetic heart of the cell, into the chromosomes. This is where you’ll find telomeres.

Telomeres, which shorten with each cell division, help determine how fast your cells age and when they die, depending on how quickly they wear down. The extraordinary discovery from our research labs and other labs around the world is that the ends of our chromosomes can actually lengthen — and as a result, aging is a dynamic process that can be accelerated or slowed, and in some aspects even reversed. Aging need not be, as thought for so long, a one-way slippery slope toward infirmity and decay. We all will get older, but how we age is very much dependent on our cellular health.

We are a molecular biologist (Liz) and a health psychologist (Elissa). Liz has devoted her entire professional life to investigating telomeres, and her fundamental research has given birth to an entirely new field of scientific understanding. Elissa’s lifelong work has been on psychological stress. She has studied its harmful effects on behavior, physiology and health, and she has also studied how to reverse these effects. We joined forces in research 15 years ago, and the studies that we performed together have set in motion a whole new way of examining the relationship between the human mind and body.

To an extent that has surprised us and the rest of the scientific community, telomeres do not simply carry out the commands issued by your genetic code. Your telomeres, it turns out, are listening to you. They absorb the instructions you give them. The way you live can, in effect, tell your telomeres to speed up the process of cellular aging.

But it can also do the opposite. The foods you eat, your response to emotional challenges, the amount of exercise you get, whether you were exposed to childhood stress and even the level of trust and safety in your neighborhood — all of these factors and more appear to influence your telomeres and can prevent premature aging at the cellular level. In short, one of the keys to a long healthspan is simply doing your part to foster healthy cell renewal.

For Healthier Aging

Your cellular health is reflected in the well-being of your mind, body, and community. Here are the elements of telomere maintenance that we believe to be the most crucial for a healthier world:

- Evaluate sources of persistent, intense stress. What can you change?

- Transform a threat to a challenge appraisal.

- Become more self-compassionate and compassionate to others.

- Take up a restorative activity.

- Practice thought awareness and mindful attention. Awareness opens doors to well-being.

- Be active.

- Develop a sleep ritual for more restorative and longer sleep.

- Eat mindfully to reduce overeating and ride out cravings.

- Choose telomere-healthy foods like whole foods and omega-3s; skip the bacon.

- Make room for connection; disconnect from screens for part of the day.

- Cultivate a few good, close relationships.

- Provide children quality attention and the right amount of “good stress.”

- Cultivate your neighborhood social capital. Help strangers.

- Seek green. Spend time in nature.