Selling Your Childhood Home: Does a House Make a Family?

Considering how much a house matters when it comes to family bonds

(This story originally ran on Next Tribe.)

Mom was sad about the daffodils. That’s why I started thinking about the sale of my childhood home.

My father died in October, and the daffodils he’d always nurtured started blooming a few weeks ago. It made my 88-year-old mother blue that he wasn’t here to see them, and, in a text group my five siblings and I created soon after our father’s death, my younger brother wrote, “She was worried that if she has to leave the house for a retirement home that she would lose the flowers.” In losing the flowers, she would lose a connection to my dad.

These are the words in this sentence that made me freeze: “leave the house for a retirement home.” Leave. The. House.

My Childhood Home: A Mocha-Brown Split Level

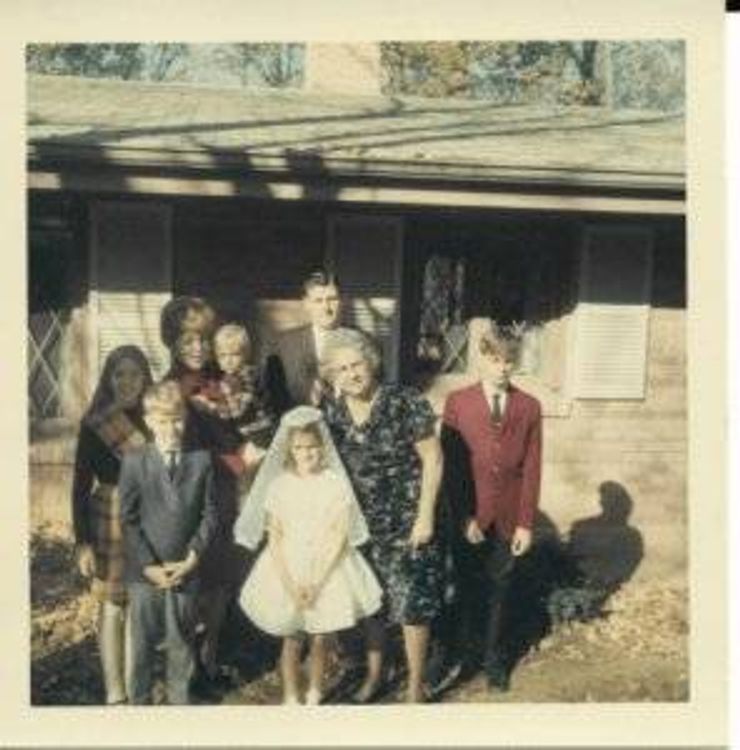

The House is a mocha-brown split level on a large wooded lot in East Tennessee. Four bedrooms, two-and-a-half baths. With a large kitchen where we spent most of our time, a formal living room where we kids rarely ventured and a recreation room downstairs where we lounged around watching a black-and-white television and raced each other up two support poles like little monkeys. Eight of us somehow managed to fit into The House, but there were always fights with six kids trying to use one bathroom in the mornings, especially when one of us (me) liked to pose in the bathroom mirror, trying out expressions and smiles in a way that young people do now, I guess, when taking selfies.

Since I left The House, it has lived in my mind as a gauzy symbol of all that was good about childhood. When I return to it once or twice a year, it is always with great reverence. Each room, each surface, contains memories: the large marble slab entryway is where Daddy and I always danced, the top of the stairway was where we all waited on Christmas morning for Dad to get his movie camera ready so he could capture us running to the tree in the living room. The House has loomed so large in my mind that, inevitably, when I visit as an adult, I marvel at how small things like kitchen counter heights feel in comparison to memory.

Now we had begun talk of letting it go, and it was the salt in the fresh wound of my Dad's death. I had a fitful night's sleep following the daffodil discussion. Without being able to visit The House, would all the memories it sparked leave me? I would no longer be able to sit at the kitchen table and see all of us gathered around it, eating my mom's pizza or arguing about whose turn it was to pick the TV show after dinner, when all of us were so much younger and starting our journeys. Now that we're on the other side of journeys and we're missing half our leadership team, The House seemed more important than ever, for keeping alive the innocence and beauty we took for granted at the time.

Remembering My Own Moves

But at some point in the night, I calmed down. I reminded myself that I'd done this thing many times before. I'm married to a restless man; we've moved six times over our 26 years together. The hardest move was leaving a two-story stone barn we had renovated into a glorious home in rural Texas. I had been the point person on the construction while my husband traveled, so I knew every nail, every floor joist and plumbing joint. It was where we'd brought our sons home after their birth.

When they were 7 and 5, my husband started talking about living somewhere else. Maybe out of the country. Since both of us were freelancers, we had a lot of freedom, but in this case it wasn't a welcome quality. I had thought we'd stay in that house for a lifetime — just as my parents had remained in my childhood home. In my mind, that was the natural order of things. But after 10 years in the house, my husband became serious. And so did I.

I put my foot down and refused to sell. In the arguments that followed, the word "divorce" came up several times.

But then, not long after my mother said I could always come home to Tennessee with the kids if I got divorced, I had a moment of rational thought. If we did split, I would lose the house anyway, so where would that get me?

I remember touching the stone walls of that house and telling myself that the house was just a thing — just sticks and rocks and concrete. It's the people, the memories that make a home. As long as we're together as a family, that's what's really important. Yeah, it's a cliché, but it didn't feel like one when I discovered it for myself at a critical, gut-wrenching moment.

That epiphany allowed me to sell the stone barn — I still had a massive nose-dripping cry when we left — and move on to new homes. A couple of them in Mexico, where we moved for four years after leaving the stone barn. More back in Texas. Whenever we sold a house, people would ask if I was upset and I would always give the same answer: I'm not allowing myself to get attached to a house again. It's just a thing.

But What About My Parents' Place?

Now, with the sale of my childhood home on the table, can my cool attachment hold? Can I see it as just a material entity? I mean, we're talking about the home from which all sense of home, for me, has sprung.

I heard something recently that gave me hope. One of my childhood friends in our neighborhood bought her parents' house after they died and a few years later — when she was done raising her own kids — moved into it with her husband.

But that's just a fantasy, that one of us would ever buy the house. Our house will be sold one day and I will have to accept that. And I have to accept my mother's right to decide what her next move is going to be.

Soon after the daffodils exchange, I asked my siblings via text how they would feel when The House was sold. A lot of anguish and sentimentality poured out in little bubbles on my phone. For the potential loss of The House, but also for the homes where they'd raised their own kids. "I have a lot of emotional attachment to places," my older brother wrote.

I'm the only one of the six who moved often. The other five are still in homes where their toddlers once roamed. I saw that maybe all my practice leaving homes I've loved could prepare me for the inevitable day of selling the big one.

Unlike when I left the barn with my husband and kids, I won't be able to console myself by saying what's important is that we're together as a family. The six of us siblings live all over the country, so we're not together physically. But then I thought of our text group. How one of my older brothers will just check in randomly; "How's everyone today?" Or how we'll share photos we came across of Daddy. Or observations on Mom's mood. Or reports on vacations. Or songs from our childhood.

I know it's fashionable to rail against technology, but I'm starting to think that when we don't have the mocha-brown split-level in East Tennessee, our flat glowing screens will be one place where we keep the home fires burning, stoking them with memories of those long-ago moments in The House where we all became who we are.