What Twiggy Taught Me About Body Image

The British 'influencer' from the 1960s was an anti-role model for teens struggling with weight

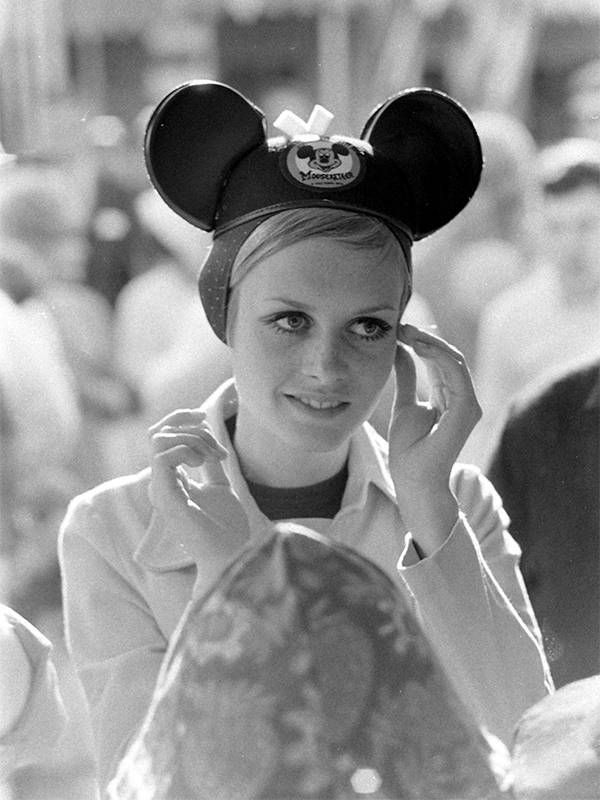

We hate Twiggy. We're teens, not feeling great about our bodies to begin with, when along she comes, skinny, leggy, with her short-short haircut that shows her face — a face we don't like. She doesn't hide it behind long hair like we do.

It's the "Swinging Sixties," and Twiggy is mod, she's Carnaby Street (a shopping district in Soho, London), everything we Beatlemaniac lovers of the British Invasion adore.

All you want is to feel attractive and now you're told curves à la Marilyn Monroe (your only role model) are no longer sexy, but straight and angular and rakishly thin is.

But she's skinny. So, we despise her.

It's 1967. You're 16 and Twiggy is just two years older and already a household name. She's 112 pounds to your 130; 31-23-32 to your 35-28-36. She looks androgynous, even though you won't learn that word for another 12 years. You want to look like a woman, desirable. But Twiggy has no breasts. She looks like a boy. And she's popular.

She stands there in all her skinniness, posing with legs akimbo, knobby kneed in her gawkiness, making skinny look weirdly appealing, while you contend with bulges and curves and feel pudgy, a curse befitting teenage girls everywhere.

All you want is to feel attractive and now you're told curves à la Marilyn Monroe (your only role model) are no longer sexy, but straight and angular and rakishly thin is. Years later people will refer to Monroe as fat.

Twiggy mocks you in her pose, making skinny look somehow cool with that pouty face that says, "I can't help it if I'm a waif, but don't you wish you were me?"

Diets and Dangerous Diet Pills

It's a Friday night and your best friend, Lynn, is sleeping over. You're stuffing your faces with Oreos, ice cream and potato chips, vowing you'll start your diets tomorrow. You truly believe you will as you lie to each other and to yourselves.

As a teen, you try the Atkins Diet, the Stillman Diet, the Exchange Diet, the Grapefruit Diet, and diet shakes.

Lynn's mother tells yours about a diet doctor and Mom takes you to see him. Maybe she feels guilty that your oldest sister was an overweight child and wants to make sure you don't go through that.

Dr. Lieberman's waiting room is packed; it's first come, first served. He gives you a shot and on your way out, his "nurse" gives you rainbow diet pills (which at the time were given directly to doctors to hand out, bypassing prescriptions) in a tiny plastic box as you pay cash. They look like candy.

The pills make you jittery, nervous and mess with your period, but you lose 20 pounds and can fit into a size 12.

A few months later, the good doctor is busted.

How Women Feel About Their Bodies

You keep the 20 pounds off and head to college. It's 1969 and free love (read: guys seducing hippie chicks) is rampant. You're 17 and getting attention. You get used, but damn, you look good.

You begin to suspect diets are a fabrication of the food and weight-loss industry and unscrupulous entrepreneurial doctors. Still, you want to look good, and that means owning a body that's average weight, at most.

You wonder what you could possibly have in common with slim people. You resent them and Twiggy reinforces the resentment. After college, you marry your boyfriend and gain a few pounds. He doesn't like it. Years later, you realize you weren't really fat, but he made you feel that way. He even uses it as an excuse for his affair. ("You'd let yourself go.")

Later you learn that even average-weight women and those considered beautiful feel badly about their bodies and, that in fact, most American women feel badly about their bodies. It's practically patriotic.

Where did this fat-shaming come from? A culture that pushes food and overeating as breezily as it pushes weight loss? Businesses that trigger binge eating and create wants, then do an about-face at New Year's and hawk weight-loss schemes fueling our resolution to lose weight?

In 1970 at the age of 21, Twiggy left fashion for show business. She says her modeling success still baffles her. "I was this funny, skinny little thing with eyelashes and long legs," she said in an interview when she turned 60, "who had grown up hating how I looked."

Wait, what? Twiggy hated the way she looked?

Fast forward 53 years. Instead of supermodels who appear only on television or in magazines, today's role models appear on social media, 24/7, where their every moves are broadcast to impressionable teens.

Today's Pervasive Social Media Impacts Teens

When I was a teenager, TV signed off at midnight, long after I was in bed. It was hard enough to figure out who I was and feel good about my body without being bombarded with perfect bodies day and night on social media.

"For today's teenagers, 'Who am I?'" has been replaced with, 'What should I look like and who should I act like?'" explains Ann Kearney-Cooke, a psychologist in Montgomery, Ohio who specializes in the treatment of eating disorders. While identity has always been hard for teens, she says, "It's to the point that some teens want to buy the same clothes and even drink the same coffee as their influencers."

Wait, what? Twiggy hated the way she looked?

Not only do teens who follow social media want to be like their role models, they truly believe they can be like them.

"Influencers seem like regular people that we might be friends with if we just did the same things they do," says Chrissy Cammarata, clinical director of Clinical Child and Community Psychology at Nemours Children's Hospital in Wilmington, Del.

To make matters worse, there are ways to enhance photos and videos to make social media influencers appear perfect. Photographs on Instagram are often manipulated, making it hard to measure up, Kearney-Cooke explains, saying, "the images teens are seeing and comparing themselves to are digitally altered. They're not photos of what real people look like."

Many teenage girls are trying to emulate unrealistic body image ideals and standards. "But, it's impossible to attain these standards, leaving most [of them] feeling let down," Cammarata says. "Most of our body shapes are determined by genetics rather than behaviors. We live in a world where thin bodies, dieting, and food restriction is equated with moral superiority, yet in reality, these concepts often lead to anxiety and discontent."

So, it looks like teenage girls feel — even more than in the past — that they're not good enough. My friends and I didn't want to be Twiggy; we wanted to hate her. She was our anti-role model. What we needed (and what today's teens need) was a role model who made us feel good about being ourselves.