The Last Gift

A final ritual for her father brings comfort

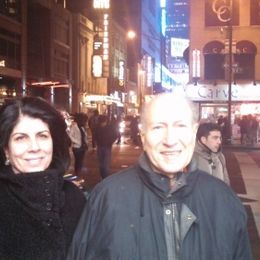

I had just finished my work for the day on a beautiful Tuesday in May when my stepmother Amal called to say my father had a heart attack. We had had false alarms before. My father was 87 and went to the gym three times a week.

As I slowly drove to New York on the New Jersey Turnpike, it got darker and darker. A doctor called about his condition at 8 p.m. from the CCU (Coronary Care Unit). I had been annoyed about another heartburn false alarm, but now I was terrified.

I was still racing on the turnpike at 9:30, when I felt and sensed a momentary black empty space superimposed on the black sky. I felt my father leave. There was an emptiness, an exhalation.

At 11 p.m., I met my exhausted family at the little hospital in Rockland County, N.Y. No one said anything about my father. I pretended to myself that he was alive and that I hadn't felt him leave earlier that night.

I felt my father leave. There was an emptiness, an exhalation.

In the CCU, he still had the endotracheal tube in. I touched his chest, which had faint burn marks from the defibrillator. He was still warm. I sat by his right side and took his hand. He had the familiar disfiguring scar between his thumb and first finger from a lab accident in his 30s. He had died at 9:30.

The next afternoon, we met at the funeral home in Sleepy Hollow, N.Y. My brothers Gamal and Tarek, and my sister Aubrey and I entered the lower level of the funeral home.

My father lay on his back, naked, with a towel over his lower abdomen for modesty. He looked like he was in the middle of a nap, except for the rigor mortis that had his arms bent at the elbow. His skin, at 87, was so beautiful and smooth. Aubrey was crying and left.

My brothers and I stood next to his body. An imam (one who leads prayers in a mosque) from New York City stood at my father's feet, which were over a sink.

The imam said, "She can't stay here," meaning me. Gamal said, "She's our sister, and she is staying."

The imam said, "It is haram (forbidden)."

Gamal repeated: "She's staying."

The imam shook his head, then shrugged. Then he began to pray and said, "I will teach you how to wash your father."

We washed him, soaping and rinsing, going in a proscribed order. It was soothing to soap up his smooth, strong chest and back and arms. I washed his beautiful face and his curly hair. Then we dried him with clean towels.

The imam showed us how to wrap him in white sheets. I kissed his forehead one more time. I folded the sheets over his face. We carried him to the coffin and laid him on his right side so he would face Mecca.

I did not expect this ritual washing to be comforting, but just something to endure. I felt it was an unexpected gift my father gave me.