The Parable of a Book Collector

Preferring to call himself ‘booklover’ rather than ‘book addict,’ this New York City resident has a collection of 70,000 books. His wife is resigned to its impact on their life.

For Sandra Núñez, living with her husband means finding packages labeled with strange return addresses outside of their apartment door, and a man returning home with illicit bundles tucked under his tan trench coat. It's been like this for 42 years.

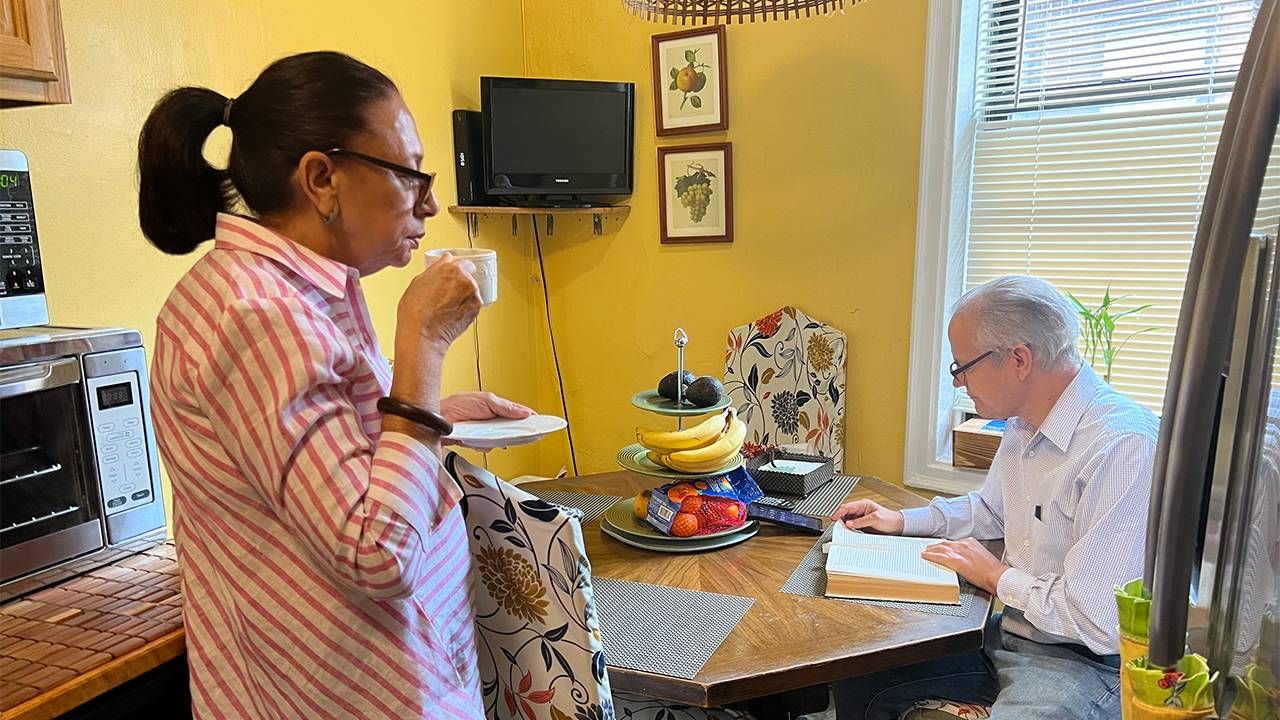

"He's not accepting that he has a problem, that he has an addiction," she said.

She exhaled. "He's addicted to — books."

Julio César Núñez suffers from bibliophilia.

"Some would call me a book addict," he said. "I prefer to call myself a book lover. I get that package. I open it. I don't care about food. I put everything aside. So there is a sort of ecstatic reaction that's almost physical."

Julio Núñez owns 70,000 books, more than three uptown branches of the New York Public Library combined.

Ramona Hernández, Director of the City College of New York's Dominican Studies Institute, noted, "70,000 is definitely a lot of books. We don't have many people like that."

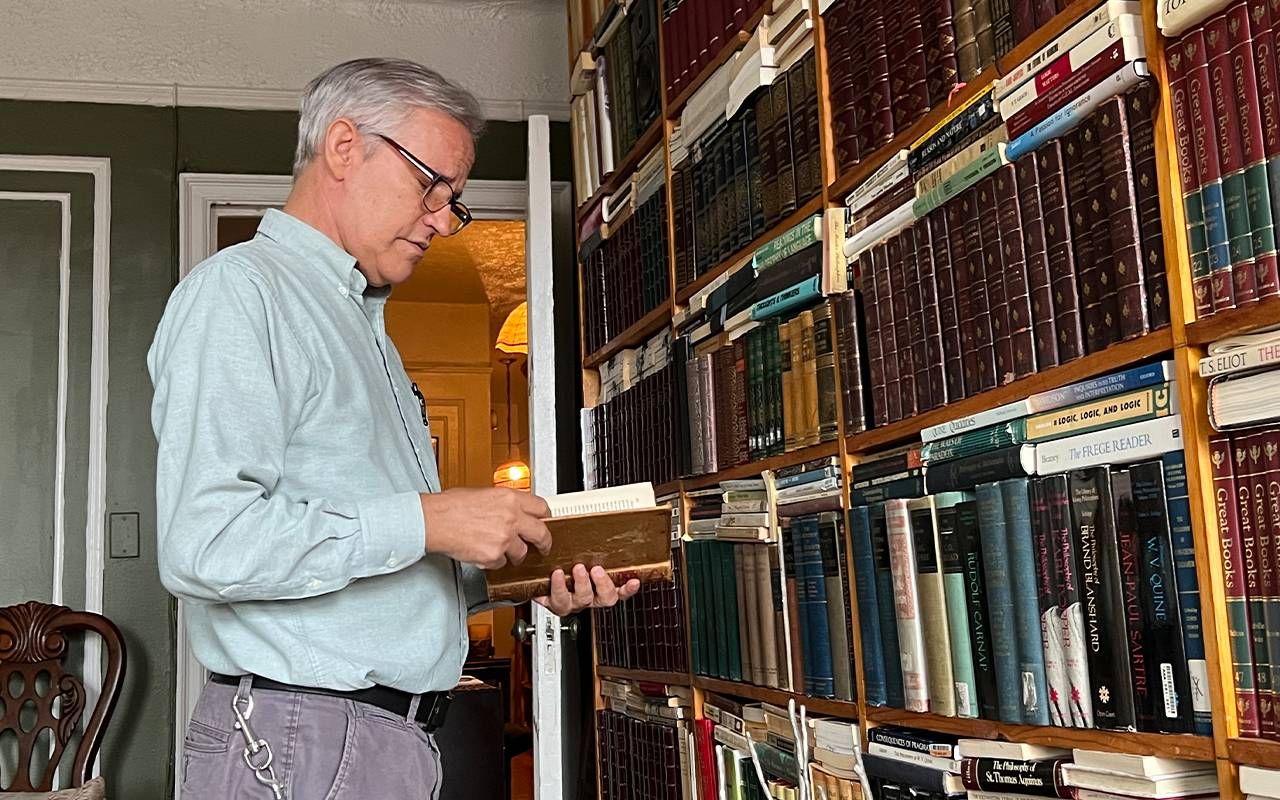

A slight man who moves and speaks with the darting quickness of a featherweight boxer, Julio Núñez tends toward button down shirts and slacks in subdued beige, blending in with the living room couch and that of the off-white paper of his books.

"I am the kind of reader that first, I ask why. I want to know what the world is all about."

He reads. Everywhere. Lying across his couch, traveling on the subway, resting in the local park, eating at the kitchen table. Walking. But mostly, on the couch.

And with one bathroom in their apartment, he avoids what many consider a coveted sanctuary.

"I'd spend an hour reading," he said, "But I have to be respectful of the space or my family would kill me."

Julio Núñez's trove of books are spread among three locations: about 20,000 on bookshelves two layers deep along with a fire extinguisher recommended by a fearful neighbor, 45,000 packed in boxes in his hometown of Martín García in the Dominican Republic and 5,000 stored in his brother's Harlem home.

Books Devour the Núñez Apartment

Volumes of written works fill wooden bookshelves from floor to ceiling. Visitors perform a semi-twist in the hallway to launch themselves inside. But you will not find pulp fiction. Or a cat.

Julio Núñez can easily pluck "Don Quixote" in English and in Spanish, a first edition of "Principia Mathematica" by Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead, the complete works of the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges in Spanish that he paid $700 for ("Sandra doesn't know that!") and the writings of Shakespeare, Tolstoy and Plato from his library.

"I consider books a very efficient means of conveying information and knowledge and I respect the knowledge that I gather from those who came before me, especially those who are much greater than I am," he said. "I am the kind of reader that first, I ask why. I want to know what the world is all about."

Sandra Núñez, with a softer rhythm compared with her husband's percussion-like bursts, eyed a pile of books in the corner. She raised her eyebrows to indicate that they were reaching a dangerous level.

A Man Rich With Ideas

The Núñezes were seven years old when they were first introduced in Martín García, and again when both were 26 and living in New York City. Their courtship began with a miniscule 100 books.

Julio Núñez's future father-in-law recognized a man rich with ideas. "If you're looking to live in a great house," he told his daughter, "Don't wait on it."

"My father's books are the fifth member of our nuclear family. My mother, brother and I have all gone through stages of cherishing them to wishing them all away."

"He was young," Sandra Núñez said of her soon-to-be husband. "I thought he was going to change."

Julio Núñez, generous to booksellers in bookstores, on the Internet, and those who peddle from tables and blankets, became a man filled with knowledge but with a wallet empty and a family second to hardcovers and paperbacks.

The Núñezes daughter learned to navigate walking routes so that her father's internal compass would not lead him to disappear into bestsellers.

"My father's books are the fifth member of our nuclear family. My mother, brother and I have all gone through stages of cherishing them to wishing them all away," said Rocío Núñez-Shea in an email. She is 39 with a doctorate in communication from the University of Pennsylvania. "My brother hates what they represent."

After Núñez-Shea, married to a writer and editor and with two young children, was born, her crib was ringed by a mere 4,000 volumes. "I haven't known a life without books," she said.

"The past 40 years," her mother said, straightening a small pyramid of magazines. "Not too good, not too bad because of his obsession. I feel that he can do more for our marriage, for our children, for himself because his life is — books only."

The Story of a Reader

As he adjusts his wire rimmed eyeglasses and reaches for "Principia Mathematica," Julio Núñez points out their value. "I see books as sort of signposts. I spend most of my free time reading and to not be able to read would just reduce or diminish the quality of life for me."

Julio Núñez's preface to reading began when his father, a factory worker with a sixth-grade education who served as mayor of Martín García, studied "Listín Diario" (Daily News), a newspaper brought home from ships docked in Santo Domingo. "He educated himself," his son said. "My mother hated books. She hated cleaning around them."

Julio Núñez was 11 when he and his family emigrated to New York in 1969. "It took me a year or two to be able to read in English. Once I did, I was the library's best customer," he said.

"Work has always gotten in the way of my reading."

The first book he owned was a children's edition of "Don Quixote," a novel published in 1605 that depicts the adventures of a man who pursued his passions and dreamed the impossible. "There is something magical about words being printed," he said.

With books under his arm and a bachelor's degree in philosophy from Colgate University, Julio Núñez's initial introduction to the workplace was as an information assistant for the New York Public Library. He moved on to directing communications for a local elected official, editing and publishing the Dominican Times and sparring with guests as the host of a Spanish language talk show. A magnet with his credo "Born to read forced to work" followed him to every job.

"Work has always gotten in the way of my reading," he complained.

Although they have lived in the same two bedroom rent stabilized apartment for 25 years, neighbors in the Núñez's six story building know little about them. The public-school teacher, postal worker and astrologer can't quite pin down what he does for a living or predict what's inside of those packages left outside of his door.

Julio Núñez retired in 2022 as an interpreter for the New York State court system. Sandra Núñez, licensed to practice medicine in the Dominican Republic, retired two years ago as a medical assistant. Both are 65.

Born in a country and living in a neighborhood where baseball has no equal and the music of merengue and bachata are as common as a cup of coffee, Julio Núñez is his own compelling character.

"I am not your typical Dominican," he said, lying across his sand-colored couch, The New Yorker magazine in hand. "Music to me is not a major thing. So going out to a ballgame or going to a discotheque or restaurant and stuff like that, I'm not into that."

Reading and Talking About Books

He has written one book and has no plans to write another. He's too busy reading. Julio Núñez self-published "Utopía Dominicana" ("Dominican Utopia") in 2010, a novel with a plot involving a Dominican patriot who rids the country of corruption and mediocrity and then rules for 50 years before disappearing. Most of the 5,000 paperbacks were distributed for free.

Julio Núñez fits into an intellectual world of men and women who debate books, politics and history and occasionally, baseball, served up with many cups of Dominican coffee in cafés and bookstores across Santo Domingo. He travels to the Dominican Republic several times a year and would hire a driver for the almost four-hour journey from Martín García to Letragráfica (Graphic Letter) bookstore and back again. But when the men and their opinions outgrew the bookstore, they moved to Zoom calls.

For three hours while his wife sleeps, Julio Núñez debates literature, politics and the state of the world with Peña Sabatína (Saturday Group): chatty ambassadors, judges, attorney generals and invited guests. The youngest is 60, the oldest 93.

After the call ends, his wife boils water for her Bustelo coffee to begin her day. She reads the work of Gabriel García Márquez and Paulo Coelho but prefers the company of family and friends. On Sundays, while her husband reads, she walks to church, bowing her head in prayer waiting for her appeal of "no more books" to be answered. With no room in the apartment for her to collect anything, Sandra Núñez has resigned herself to a life surrounded by words.

"I've gotten used to them," she said of her husband's books. "They are a part of me. I miss them when I am away."

Pondering His Final Chapter

To support his obsession and to pay off the 1,200 acres of land he recently purchased in Martín García, Julio Núñez continues his work as a court interpreter on a per diem basis. His hometown, 40 minutes from the Haitian border with just over 1,200 residents but no library, offers Núñez plenty of space to read undisturbed.

"I was thinking last night about what I want in my coffin. I would love a book."

Julio Núñez's dream, perhaps not an impossible one, includes building a library to house his collection of poetry and prose for booklovers like himself.

An architect cousin designed a seven-story cylindrical tower very much like a lighthouse but with a balcony encircling the top as a beacon for readers. A spiral staircase flanked by bookshelves, chairs and small tables is intended for floors dedicated to reference, art, science, history, literature, philosophy and theology.

Julio Núñez plans to sit and read when he and Sandra retire to Martín García in 2025. He also plans on building an ecological center to revive the local bird population which disappeared when pesticides were sprayed on the land, and a ecumenical center to bring people together.

Julio Núñez has already skipped ahead to his final chapter.

"I was thinking last night about what I want in my coffin," he said. "I would love a book. That book would be Homer's "The Iliad and the Odyssey." I love the greatness of these two magnificent works in the sense of the language, and the mastery of drama in the beauty of the language that Homer uses. I want to convey, as my last message, that life is like a journey."

The mail carrier knocked loudly at the Núñez door.

"I've been waiting for this book!" said Julio Núñez of science fiction writer Isaac Asimov's memoir in Spanish. "Sandra is going to kill me."

"He doesn't change," Sandra Núñez said. "Nothing changes."