Old Friends: The Story of a Guitar and a 50-Year Relationship

When is a guitar more than a wooden box with strings, when does it contain a soul, stories and secrets? A partial biography of a guitar and those who played it.

After playing with toy guitars (yes, I had a Mousegetar) and a cheap mahogany uke from Sears (which had the lovely aroma of wood), by 15 I had a real guitar and began to play fingerstyle using a songbook by Peter, Paul and Mary. My family had moved to a Minnesota city from the small Iowa town where I was born, and my teen angst was amplified by loneliness — having a guitar to play in my room was medicine.

A couple of years later, I took a summer job as a "deckhand" at a North Dakota camp next to the Canadian border. My parents put me (and my Martin D-18) on the long train ride from St. Paul to Minot, and I traveled alone for the first time.

My job was a mixed bag of maintenance and support for the day-to-day operations of the camp. I quickly fell in love with the place and the rest of the staff. My favorite part of the job was playing guitar for the numerous daily singalongs, providing me with a kind of musical training, increasing my skills with chords, keys, rhythm and strumming styles.

One of my best new friends was John Ydstie, who came from a tiny prairie town nearby. Over the course of the next four or five summers I spent in North Dakota, high school turned to college, and we grew from boys to young men while falling in love with girls and struggling with the morality of the Vietnam War and anxious about our draft status.

The Gibson J-45

We became real guitarists during those years. The hours spent playing "If I Had A Hammer" at hootenannies or sitting on the tailgate of a red 1951 International Harvester pickup playing Doc Watson's "Victory Rag" for the young campers were enhanced by late nights in a cabin working on Paul Simon tunes and new picking styles.

We looked at it through the window for a minute and then went inside to see it up close. It was very playable, sounded great and the price tag read $100.

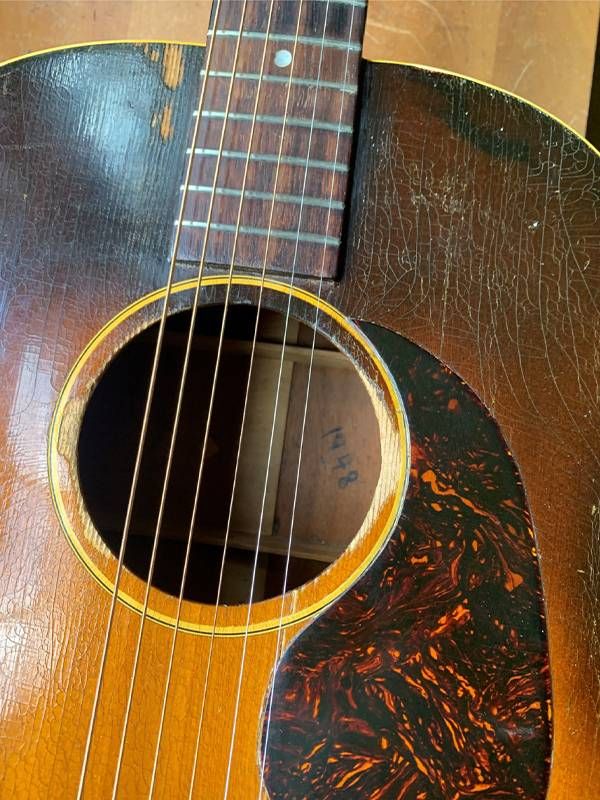

One day in July of 1972, John and I were walking down a street in Minot when we saw a guitar in the window of a music store. It was a well-used Gibson J-45, the finish worn through in places and with an odd repair on the body near the strap button that appeared to be plastic wood. But even with its cracks and superficial flaws, it had a patina that was rich and irresistible, as though it had secrets. Someone had inscribed "1948" inside the sound hole with a blue pen. We looked at it through the window for a minute and then went inside to see it up close. It was very playable, sounded great and the price tag read $100.

Neither of us had much money, but we decided not to pass up the opportunity to own this intriguing guitar, so we pooled our funds and agreed to share the instrument. We would be back in college in the fall, John in Moorhead, Minnesota and I in Decorah, Iowa — close enough for trips to connect and hand off the guitar a couple of times a year.

The late 1940s Gibson J-45 (J for "jumbo") was, in Gibson's own words, the "workhorse" of American country, folk and blues music. It was a populist guitar — if a Martin guitar was a Mercedes, the J-45 was a Ford truck. Woody Guthrie may have written "This Land is Your Land" on one, and Doc Watson, Bob Dylan, and Emmylou Harris, among many others, played it. Jeff Tweedy of Wilco has said "If there is one tool the singer-songwriter should have, it would be the J-45".

For seven years, John and I passed the guitar back and forth, until 1979, when he and his wife moved to Washington, DC, and John began working for National Public Radio.

While I was preoccupied with my life decisions at the time, I fell in love with the Gibson. I still played the D-18 (the main competitor of the J-45). But during my periods of stewardship of the Gibson, I played it the most, loving its deep, powerful tone and rich bass.

I also could not separate the guitar I was holding from my memories of nights spent with John playing music and wondering who had owned the guitar before us. Could it have been Woody? Hank Williams? Who came on such hard times that they had to sell the instrument to a Minot music store? This guitar had stories that it could not reveal.

For seven years, John and I passed the guitar back and forth, until 1979, when he and his wife moved to Washington, DC, and John began working for National Public Radio. When they pulled away in their rental van, the guitar was in my house. We promised to continue to share it and to make it the thread that would hold our friendship together over time and distance.

Over the next twenty years, we started families, continued our educations and began our careers. The distractions of adulthood made our visits increasingly rare and even letters became very occasional. For two decades, the Gibson remained in my possession. I still played it often and spent many nights sitting on the floor next to my young son's bed, playing while he fell asleep.

The Value of Our Guitar

By 1999, I began thinking that we should get back to exchanging the guitar, or perhaps I should buy John out. My first thought was "I'll give him his $50 back." But we were both aware (and had been even in 1972) that this guitar was worth more than we'd paid for it.

"Its story is part of our story now; a love triangle of the best kind!"

Before I raised the idea of a possible buyout, I thought it would be a good idea to find out how much the guitar was now worth. I took it to our local St. Paul vintage guitar shop (Willie's American Guitars) and had owner and guitar expert Nate Westgor look at it. His conclusion was that our old $100 Gibson was worth over $2,000. Why? It is the wood … and the country's need for music and joy after the end of World War II.

"Your guitar is made from mahogany that was likely cured for decades before seeing a kiln. We believe that the guitars of this era sounded fantastic when new … but they get better and louder with age" said Westgor recently. "Gibson only made professional level instruments at this time … After World War II, the world was ready to relax and dance halls became popular."

The J-45 addressed the need for louder acoustics. He said, "The electric guitar was invented out of need to reach these huge audiences — and changes made in acoustic design to add volume made the value of lighter braced acoustic guitars go up - values increased in the 1950s and continue to increase historically at over 10% per year."

I called John with the news that our guitar was gaining value, and, after a moment's pause, he told me that his share was not for sale and that it was his turn to play it — admittedly, a completely fair reaction.

The Story of Our Guitar

We decided that the guitar, an enduring symbol of our relationship and an object that represented so many memories, had more than monetary value. We renewed our agreement to pass it back and forth and made plans to meet in musically important cities to make the handoff. Soon we were in Memphis for a weekend where I passed it back to him again.

In 2000, John wrote and produced a 9-minute story for radio about the guitar, which aired on NPR's Weekend Edition Saturday. It was a lovely piece, with John and I chatting while he played. The story received a lot of reaction from listeners who'd paused during their Saturday morning pancake making, dog tending and other chores to listen to radio done so well. John shared the comments with me, and it felt like the old guitar had again become something more than a musical instrument, that is was a symbol of the importance of maintaining connections.

As John says: "Its life with us has been a sweet blessing. First, of course, for the wonderful sound that emanates from its wood, its soul … always ringing pure and pitch perfect. Maybe most important for me is that it's been a force, a third being, that's helped keep our friendship alive and growing, despite the physical distance between us. Its story is part of our story now; a love triangle of the best kind!"

Westgor has assessed the guitar two more times — in 2010, he told me it was worth over $8,000 and that I needed to get a "better case." Just this summer, he looked at it again and said "$15,000, and you need to insure it." Our $100 investment has increased 14,900%.

But more importantly, this is a guitar with a life story, a story that only comes out when it is played. It has given pleasure to players and listeners, and not only is it older than us, it is going to outlive us. It reminds me of one of the central principles of Buddhism — that nothing lasts forever, that everything is ephemeral and that we must cope with the pain that results from our love of impermanent things (beauty, flowers, dogs, parents). But in this case, John and I have a love for something that is more permanent than we are. Something with secrets and soul.

Now when I play Paul Simon's "Old Friends," it is with a different perspective, and it is with gratitude for lifelong friendships. At 20, the lines "can you imagine us years from today/sharing a park bench quietly" might have gone over my head but now they are full of meaning and love and music.