When Sports Writers Ruled TV

How a squad of wisecracking old-school newspapermen shaped today’s sports media landscape

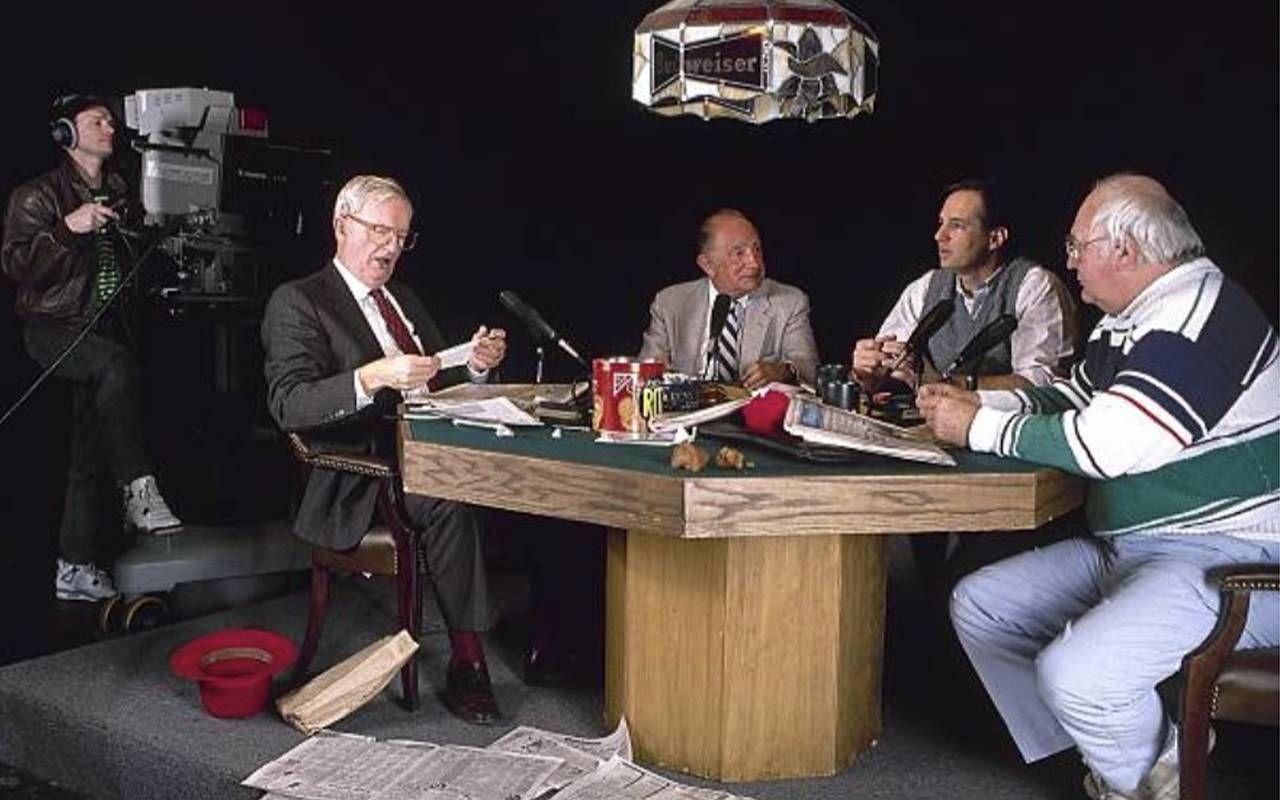

"The Sportswriters on TV" may have been the unlikeliest hit of early cable television. The program consisted of four men — three sportswriters and a boxing ring announcer — sitting around a poker table littered with newspapers and ashtrays, talking for an hour.

Chicagoans to the core, they spoke with a joyous parochialism about topics local and national in nasal and gnarly local accents. Three regulars on the program were well into middle age, including a guy born during the Wilson Administration (Ben Bentley, the ring announcer), one born when Harding was president (Bill Gleason, a Chicago Sun-Times columnist), and a Hoover baby (Bill Jauss of The Chicago Tribune). The youngster on the panel, Sun-Times columnist and Sports Illustrated feature writer Rick Telander, was in his mid-thirties.

Heirs to Ring Lardner

None of them wore makeup or knew how to use hairspray. Jauss sometimes wore a sweatshirt from a local bar. Bentley and Gleason smoked cigars from start to finish. The three wisecracking colleagues acted as if "Young Telander from Peoria" was a naïve adolescent who rolled into town on a farm truck.

The program aired in Chicago beginning in 1985. Two years later, SportsChannel, a longtime ESPN competitor, started carrying it nationally.

Amid the flashiness of the 1980s, "The Sportswriters on TV" became a cable staple. It never seemed to be on when scheduled, preempted time and again by live sporting events. At the same time, it seemed ever present on rainy afternoons or quiet evenings when viewers flipped through the dozens of new cable channels looking for something worth watching.

By decade's end, the program was available in more than 10 million homes. Within a few years, viewers in all 50 states could watch the "Sportswriters" panel's candid, opinionated and informed discussions.

Filling Time with Talk

The program spawned several imitators before it went off the air in 1998, when SportsChannel merged with Fox Sports. Now, the show's talking-head descendants fill the schedules of every form of sports broadcast media. Twenty-four-hour sports coverage on cable television and sports talk radio feature a cacophony of debate programs.

While "Sportswriters" was built around the rhythm of conversation and longstanding rapport, its imitators on cable networks today often truck in calculatedly provocative comments called "hot takes," split screens and prefabricated talking points.

Online, the freeform, hyper-specific world of podcasting is a direct successor to "Sportswriters" — a television program that was like a barroom conversation among familiar, opiniated friends who were all blessed with interesting life experiences and supreme skills as storytellers.

The world that "Sportswriters on TV" hath wrought began on the radio. In 1975, Chicago Sun-Times sportswriter Bill Gleason created a Sunday afternoon program called "The Sportswriters Show" on WGN, one of the city's top radio stations.

"Gleason saw around the corner. He knew that people would be happy to listen to the kind of conversation they had themselves about sports."

Gleason brought along Tribune colleague Bill Jauss and the Tribune's sports editor George Langford. To host the show, he hired Bentley, a former middleweight fighter who was for decades a press agent, boxing promoter and ring announcer in the city.

"There was not a lot of sports discussion in the world of broadcast," longtime Sports Illustrated writer Lester Munson said of "The Sportswriters Show." Munson is a Chicago-based lawyer turned sportswriter who appeared frequently on the television program's later seasons. "Gleason saw around the corner. He knew that people would be happy to listen to the kind of conversation they had themselves about sports."

Enter John Roach. A Madison, Wisconsin-based television producer, he came across "Sportswriters" on the radio while commuting into Chicago. It reminded him of the talk at his father's poker table, where a group of buddies that included Big Ten football and basketball officials traded in behind-the-scenes scuttlebutt while occasionally making it through a hand of five-card draw.

Working closely with Gleason, Roach created "The Sportswriters on TV," which debuted on Chicago's WFLD TV in December 1985. Almost immediately, the show found an audience among people who, like Roach, thought they were listening in on a conversation that had been going on for decades.

"There was no showboating for TV, there was no playing to the camera. . . . No fake opinions, nothing taken up just to be controversial."

"It was the first show of its kind. We were authentic," Telander said. "There was no showboating for TV, there was no playing to the camera. It was just pure honesty. No fake opinions, nothing taken up just to be controversial."

When the cable show started, Jauss was 54, Gleason was 63 and Bentley was 65. Roach joked that he added Telander to the show "because they needed somebody without a prostate problem," Telander said. The dynamic worked well from the outset.

"Sportswriters" looked and sounded like nothing else on television. Despite the demographics of the program's panelists, it was the substance of the show, not merely its aesthetics, that won it a sizeable viewership.

Substance over Style

"I never felt like we felt old or that our audience was old," Munson said. "We felt like we were doing lively stuff with some energy and vitality. I used to be glad that I wasn't the oldest person in the room with Jauss and Gleason. On ESPN, I'd be the oldest guy in the room all the time."

Chicagoans have a long history of finding the universal in the particulars of their hometown. From James T. Farrell and Richard Wright to Studs Terkel and Mike Royko to Oprah Winfrey and Barack Obama, something about creative people from Chicago makes them capable of reaching a national (and certainly now international) audience by telling stories rooted deeply in the City by the Lake.

"The personalities, in particular of Gleason and Bill Jauss, were made for broadcast and caught hold right away," Munson said. "People liked the cigars, they liked Gleason and his hats, they liked Jauss with his indignation over various things."

"What happened in Chicago was always important. You think about the great athletes and the great teams we had during that era."

Focusing on the Windy City was an asset, not a liability, Telander said. "It was hyperlocal," he acknowledged, "but what happened in Chicago was always important. You think about the great athletes and the great teams we had during that era."

The duration of the show corresponded with a uniquely vibrant period in Chicago sports. It first aired during the Super Bowl run of the Mike Ditka–Walter Payton Bears. It thrived through the basketball dynasty of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls. Its final season corresponded with Chicago Cubs slugger Sammy Sosa's pursuit of baseball's single-season home run record.

Add to this the fact that everyone involved with the show was a genuine character.

"Gleason had that voice and that sense of humor and that wonderful cynical attitude on life."

Gleason, a South Sider, began his 60-year career in journalism as sports editor for the Southtown Economist at age 19. During his time on "Sportswriters," the proud Irish-American and White Sox fan worked primarily for the South Bend Tribune. He donned a ballcap or a fedora almost every week and punctuated his sentences with his cigar while he spoke.

"Gleason had that voice and that sense of humor and that wonderful cynical attitude on life," said Munson. "He was the real thing. The television program was Gleason and Roach's baby. The feisty pair had it out on plenty of occasions but in the end always hashed it out for the good of the show."

Jauss spent most of his 50-year career with the Chicago Tribune. He displayed a particular passion for day-to-day coverage of high school and college sports.

"One of the sweetest men in the world with one of the most passionate voices and concerns about things," Telander said of Jauss. "This wasn't a mean guy but if he believed in something, oh my God, look out."

"Jauss was such an original character," Munson said.

"He absolutely did not care about the trappings of luxury and comfort," Telander recalled.

Representing the Everyman

"Jaussy" did not know what make or model of car he drove, only that it was probably blue. He looked the part of the everyman and spoke on his behalf, all the while teaching journalism at Northwestern University, his alma mater.

Bentley, on the other hand, dressed in tailored suits and worked with the likes of Sonny Liston, Sugar Ray Robinson and Rocky Marciano during his decades in the fight business. He had a booming voice steeped in a Chicago accent that elongated every vowel that reverberated from his voice box. A PR man, not a sportswriter, Bentley was a masterful storyteller and jokester. His charm set the tone for the program. Each episode opened in mid-conversation before Bentley brought the table to order.

"I loved Ben," Telander said. "He was, underneath that fog-horn voice and the cigars, one of the nicest men that I've ever met."

Birth of a Sportswriter

Telander was the youngster they needed to set straight. Despite being a young whippersnapper, he had known the other three for decades before joining the show. He met Bentley early in his career as a freelance writer. Bentley, then a public relations man for Chicago's Park Department, got Telander and his buddies ringside passes for boxing matches at municipally managed venues.

A few years earlier, Telander, then a standout defensive back at Northwestern, ran into Jauss and Gleason as reporters covering Wildcats football. Gleason had once interviewed him extensively for a feature story on Northwestern's defensive backfield, peppering him with off-the-wall questions that Telander answered just as provocatively.

"At one point," Telander recalled years later, "he [Gleason] stops and kind of puts his hat back and says 'Telander, you want to be a writer, don't you?' He was the first guy to ever suggest it. The first guy to ever notice it." Gleason's offhand comment was life-changing encouragement for Telander, who had quietly harbored notions of becoming a writer but had never shared the idea with others.

A Winning Formula

Telander excelled at bringing topics to the show, particularly subjects of national interest. The program's format consisted of seven seven-minute-long segments, allowing the foursome to cover much terrain each week.

"Roach is very smart, very clever," Telander said. "He was the final arbiter of everything. He has to produce everything. . . . The show never would have happened without him and it never would have continued without him."

Bringing Telander on board proved to be one of many great decisions by Roach, the architect of the television program. "Telander could get ready on things and dazzle you with his language and his reporting," Munson said. "He always had excellent ideas on what we should talk about."

The panelists prepared for each show by talking by phone during the week and then meeting to finalize the list of topics right before the show was taped.

Rehearsed but Spontaneous

"We would gather in the studio an hour or hour-and-a-half before we started to tape," Munson said. "Led by Roach and Gleason, we would talk about what are the issues for today. We were always conscious of hitting on the important national stories while keeping it a Chicago kind of thing. Roach was the scorekeeper and would make sure that we were balanced."

Gleason also focused on keeping the show's sense of spontaneity by imploring his colleagues to "save it for the show" by not laying out all of their points in rehearsal.

Recurring health problems forced Bentley to retire during the mid-1990s. A series of regular contributors joined the panel, including veteran Chicago writers Lester Munson, Joe Mooshil and Mike Mulligan. At the time, Munson wrote for Sports Illustrated but remained deeply rooted in Chicago.

"I had been a huge fan of the show," Munson said. "I used to go out of my way to listen to them when they were on the radio. I watched them every chance I got on television. It never occurred to me in a hundred years that I would end up on that show. I viewed it as one of the great opportunities of a lifetime."

A Respite from Coastal Dominance

"Lester is a great guy and I really had a great time with him," Telander said. Though the show's tone was always a bit different without Bentley as the raconteur/traffic cop, contributors like Munson helped the show maintain its unique feel.

"The fact that the four of us were so connected to Chicago and had been for so long, it had a sincerity and an integrity," Munson said. For the duration of its run, "Sportswriters" was a respite from the East Coast–West Coast dominated sports news cycle.

"We opened the door for a lot of different things."

After 13 years, "The Sportswriters" came to an end, just as it seemed that all other sports channels had filled their schedules with similar commentary-driven programs. Turn on the television right now to see the legion of imitators. It started with the sedate Sunday morning "Sports Reporters" on ESPN, a forerunner to the network's afternoon stalwart, "Pardon the Interruption," which begat a dozen other cable television imitators and hundreds of daily sports talk radio programs. Unlike the genuine conversations on "Sportswriters," most such programs have taken on the tropes of either game shows or shrill political debate shows.

"I don't blame anybody for imitating it but there was one original and that was it," Telander said. "It was authentic. It was real. It was difficult for other shows to duplicate it, this brotherhood that we had."

"We opened the door for a lot of different things. We dug deeper, we were more nuanced, we were more detailed in our conversations. The sports talk that I see now is not really done at that same level. [Tony] Kornheiser and [Michael] Wilbon on PTI (Pardon the Interruption) are the closest thing to what we were doing. I love listening to the two of them," Munson said.

Final Innings

Three of the four original cast members have died: Bentley in 2001, Gleason in 2010, and Jauss in 2012. Telander, now in his seventies, is the last survivor among the original four.

"I really miss all those guys. It hurts," Telander said.

Lester Munson, now in his eighties, shares that pain.

"I was very sad to see the program come to an end," Munson said. "I looked forward to doing it every week. I loved the challenge of getting ready and keeping up with Gleason, Jauss and Telander. I miss it even now."

In the early 2010s, Roach repackaged some old "Sportswriters" episodes with "Pop-Up Video"-style factoids appearing on the screen, but this funky take on reruns didn't last long.

At this point, "The Sportswriters on TV" has not been broadcast for nearly a quarter-century. At the same time, its descendants can be seen everywhere you watch sports, but with little of the original's charm.