Why You Should Write Letters to Your Kids

My family and I get joy from the memories I've put down

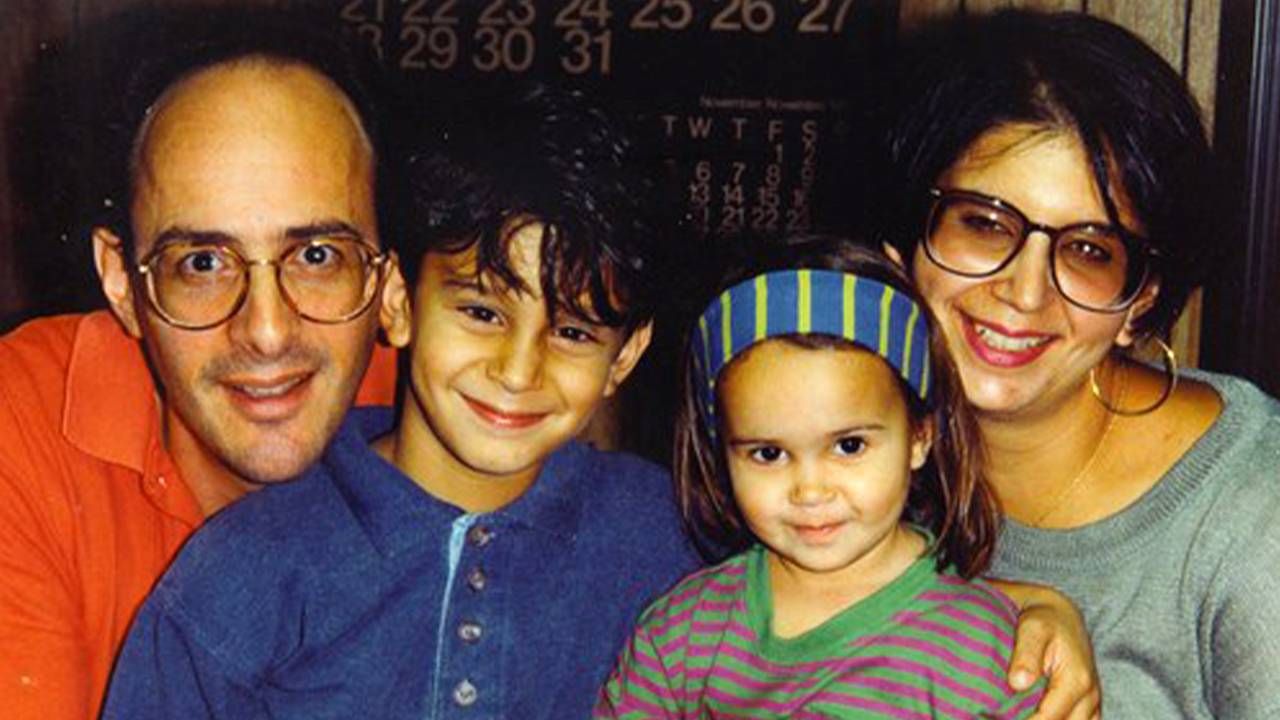

As I approached 50, I promised myself I would chronicle my personal family history exclusively for our children, Michael and Caroline. By then, both were already teenagers.

How hard could that be?, I asked myself. I'd long written for newspapers and magazines, even a book. But I'd never done so for the kids.

A year passed, and then another, without my getting around to it. Too many distractions — like earning a living. I always found excuses.

I documented my life as a boy, a young man, a newlywed and as a father.

But on January 1, 2008, when Michael was 24 and Caroline was 19, I finally buckled down. Every weekend, I set aside about an hour to jot down memories in a journal for each child. I cast the entries as "letters," addressing my son and daughter. My kids had no idea.

Why I Started Writing Letters to My Children

I pursued this project because I had discovered myself at last to be old enough to have a past and more inclined than ever to reflect on it. I recognized, too, that I now had something worth saying and might even know how to say it.

But I had other, deeper motives as well.

Neither my mother nor my father had ever written down anything about their family history for my sister and me. Both are now gone. It's too late to ask questions — like why they married each other or how they felt about becoming parents. And now, so much that happened is forever lost.

I vowed never to let that happen to our children.

In the journals, I documented my life as a boy, a young man, a newlywed and as a father. I recounted how the day Michael was born he took his time — 36 hours! — emerging from the womb. How Caroline, at 7, boldly climbed atop a boulder on a beach to sing a song from a Disney movie for us and our spellbound friends.

I captured my struggles being raised by, and attempting to communicate with, parents who happened to be profoundly deaf. I even confessed how poorly I behaved in school and performed academically until reaching college, and how a dumb, drunken remark late at night almost blew my first date with the woman who is now my wife of 42 years, Elvira.

As I wrote, I asked myself questions I imagine so many parents and grandparents might now be asking themselves amid the COVID-19 outbreak: What do our children need to know about me and our wider family and themselves? What should I report about the lives we've all lived?

After all, the journals would serve as a record, a keepsake, that could be read in decades to come.

By December 2008, I had completed 50 little essays, averaging about 500 words each. And on Christmas morning, I gave each child a journal as a surprise gift.

Later, after reading the journals, they told me how much they appreciated my effort and how much they had learned. So, in 2009, I repeated the deed, again without the kids knowing, again bestowing a Christmas surprise.

After stalling for years, I had finally delivered on my promise.

Taking the Letters Public

In 2010, I got the idea to take these private journals public. Maybe, I suspected, other people would benefit, perhaps even be inspired to follow suit.

But first, I asked Elvira, Michael and Caroline for permission. Eventually, after their initial reluctance, they gave me a thumbs up. So I started a blog called "Letters to My Kids."

If nobody documents personal family history, I knew, it will be doomed to disappear.

I started posting the first of some 100 letters on Father's Day. But I soon realized the blog should be about more than just me and my family. So I invited friends, relatives, colleagues and neighbors — all mothers, fathers and grandparents — to contribute guest columns.

More than 80 people around the world (average age: about 45) obliged. Their columns, from as far away as Saudi Arabia and Norway, turned out to be poignant, sometimes wrenching. One father told about raising his deaf son. A mother revealed how one day she tumbled from the top of her stairs holding her newborn baby in her arms, with both luckily surviving undamaged.

I also posted dispatches about letters from parents to children throughout history. As it turned out, most U.S. presidents, from Washington and Jefferson to Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and Barack Obama, had left similar legacies.

My blog sought to serve a higher purpose. I urged parents and grandparents to take a pledge. They, like me, would promise to do what I had done and preserve family history in writing for the benefit of future generations.

Keeping such intergenerational storytelling alive seemed important to me. Computers, smartphones and social media eat into time otherwise available for sharing personal family history. Posting family photos on Facebook and texting your child "I love you" is all well and good, but these tactics are only piecemeal and scattered. Casual conversation at the family dinner table, even during Thanksgiving or Easter, might be limited. Multiple generations seldom live under the same roof any longer, rendering reunions increasingly rare (even more so during the pandemic).

The Importance of Documenting Family History

If nobody documents personal family history, I knew, it will be doomed to disappear.

That's why I believe we should, in effect, invest in our pasts through such letters. Even the best intentioned oral storytelling often evaporates into the air without a trace, soon forgotten. But creating a record lends permanence, sending a message out into the future.

No one knows what will happen tomorrow, least of all now, with the coronavirus on the loose. The pandemic implicitly insists that we reckon with the lives we've lived. It compels us to ask what our lives have meant and whether and why they have mattered. It also, I believe, compels parents to pass along any lessons we've gleaned to our children and grandchildren.

More than ever, the prospect of leaving our children ignorant about our pasts haunts us. We should all feel an extra incentive, a newly heightened responsibility, to go on the record and act as witnesses to our own histories.

As our mortality stares us in the face, writing personal family history enables us, without blinking, to stare right back.

It's easy enough to send "letters" to your kids. For starters, promise yourself to see it through. Schedule time every week to put down some recollections. Tell your children what your life was like (in earlier days and currently) and how it felt. Detail your origins, your sufferings, your triumphs. Be spontaneous. Speak plainly. Keep it real.

In the process, you might manage to make sense of your life and come across new truths about yourself. It could be therapeutic, even revelatory. It's your chance to say: I was here, I lived, I mattered.

Today, more than a decade after my first letters, here's what my children say about them:

Caroline, who plans to follow my example for her 2 1/2 year old daughter Lucia Antonia someday, says: "My father remembered so much more about me as a baby than I ever expected."

"It was eye-opening," Michael says. "I learned a lot about your life, before you became a father, that I never knew."

So, parents, please take the cue from this once-in-a-century wake-up call. But do it for your children and grandchildren.

Do it because they will know once and for all what they most need and deserve to know. They'll see with absolute certainty that you paid attention all these years, that you remember even the small details, and that, above all, you love each one with all your heart and soul.

That legacy will prove more lasting than any heirloom or insurance policy.