Writing a Eulogy for My Father

In this book excerpt, the author remembers her dad who is gone, but ever-present

(This is an excerpt from Starting with Goodbye: A Daughter’s Memoir of Love after Loss published by University of Nevada Press, May 2018.)

My favorite part of any funeral is the eulogy. Perhaps it’s strange to have a favorite part of a funeral. But I do.

The terrible and wonderful thing about a eulogy is that it is not a forgiving genre: One is a composer conducting without rehearsal and with one arm injured. There’s typically little time to mull, to think deeply; a eulogy is one of the early tasks in the business of grief, demanding we find perfectly nuanced space between sentiment and sentimentality without much chance to revise.

You normally only get one chance. I got two chances. I delivered my father’s first eulogy, which I thought of then as the only one, in Las Vegas, where my parents had retired 25 years before; a subdued service in a nondescript, nonsectarian funeral home near their house.

I delivered the second back in New Jersey at a memorial service for family and friends — where Dad was born, worked and lived for 55 years and where I was still living, where I live still — in a quietly elegant Catholic church.

A Eulogy as an Assignment

I got it mostly right, but also wrong both times, unsure even now if I was talking mostly to myself, to the gathered mourners or to my father.

I was 46 and had spent 40 years writing. On the airplane from my home in New Jersey to Las Vegas, I approached the eulogy at first as a job, turning around fast copy about an untimely death. I could draw on a few scraps of experience, all more than 20 years before, all connected to horses. Once, at a Santa Barbara horse show, about 10 feet in front of me, an Olympic-level horse named Hai Karate dropped dead mid-jump over a huge fence. Two horse-show judges perished in a fire. A trainer died in a horse-van accident.

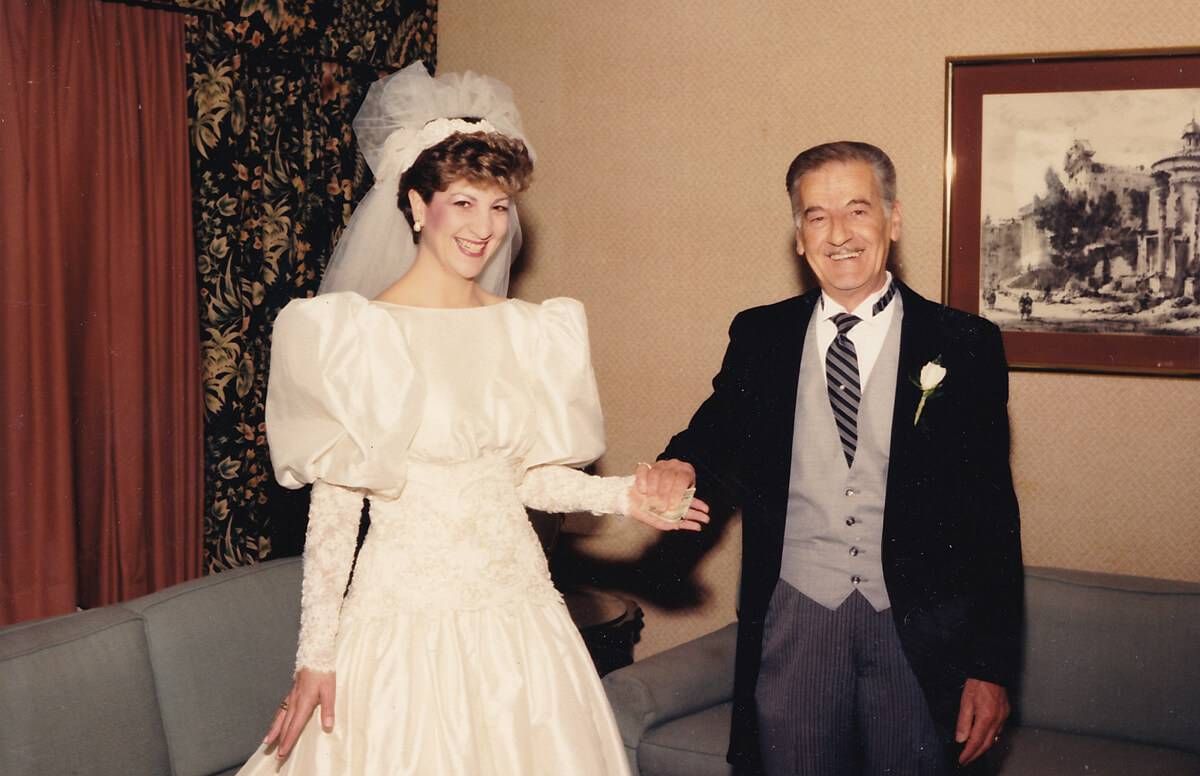

I’d written about these events in The Chronicle of the Horse, for which I’d been a contributing writer. The gig allowed me to stay on the horse show circuit, competing on two expensive horses, courtesy of my father’s polyester-factory money and my mother’s eager prodding about living a “flight of fancy.”

But I was rusty at the job, no longer that young reporter, committed to checking facts, getting everything exactly right, making sure my own narrow view was balanced by the bigger picture. It showed.

Writing About Someone I Didn't Know Well

Anyway, something else was going on.

With the first stroke of the pen, at 31,000 feet, above Indiana or Colorado, it occurred to me it was the first time I’d written more than a line or two about my father. What I was doing, I could never have done during his lifetime: write about a father I didn’t know well.

This man — who it would turn out, in death, I would keep returning to — was the same man I had kept turning away from while he was alive. It felt, from the start, like atonement.

I did what I could. There were moments when I could not bear to look down at the page. Many more when I could not look away. We write what we can at those moments, knowing there is no time to dither, to linger. Yet to linger is all we hunger for.

When I tried to write that first eulogy, I had no idea I would write a second, and not an inkling that so much more would transpire, that I’d get a second chance to know that unknowable father. But if anyone’s grief can have a theme, that was mine, or ours: a second chance. Heavens knows, we needed one.

In life, I’d mostly ignored him. In life, my father had not evoked strong emotion in me or I mistook what he did evoke as something else. I thought the bickering meant we didn’t like one another, but in fact it meant we were too alike. He knew I was like him in fundamental ways; I had always hoped he was wrong.

Having Conversations with My Father

In the days after my father’s death, I was struck by a yearning so powerful, to know him, to understand his story, to figure out our story. And so, we started talking.

We “talked” more after he died than before. He (his spirit? my conjuring? my grief mind?) dropped by for chats: in the doctor’s waiting room, at my kitchen counter dawdling over coffee, in my living room late at night when I was reading, on the patio while I was carrying groceries to the back door. We talked, and we were quiet with one another, too. I got used to this, and came to think of the quiet spaces in those visits as part of our “conversations” too.

In our second relationship, we seemed to interact without the strain of his always needing to be right and my always needing to prove he wasn’t. But can a relationship really continue, and even get better, when one of the two is gone?

At the time, the woman I was — frugal, pragmatic, a lapsed believer, writing a eulogy she thinks of as work — would not have thought so. I was wrong.

Maybe the eulogy is never finished. Because the relationship is never finished.