A Conversation in an Artist's Studio

Minneapolis artist James Wrayge talks about the adventure of painting

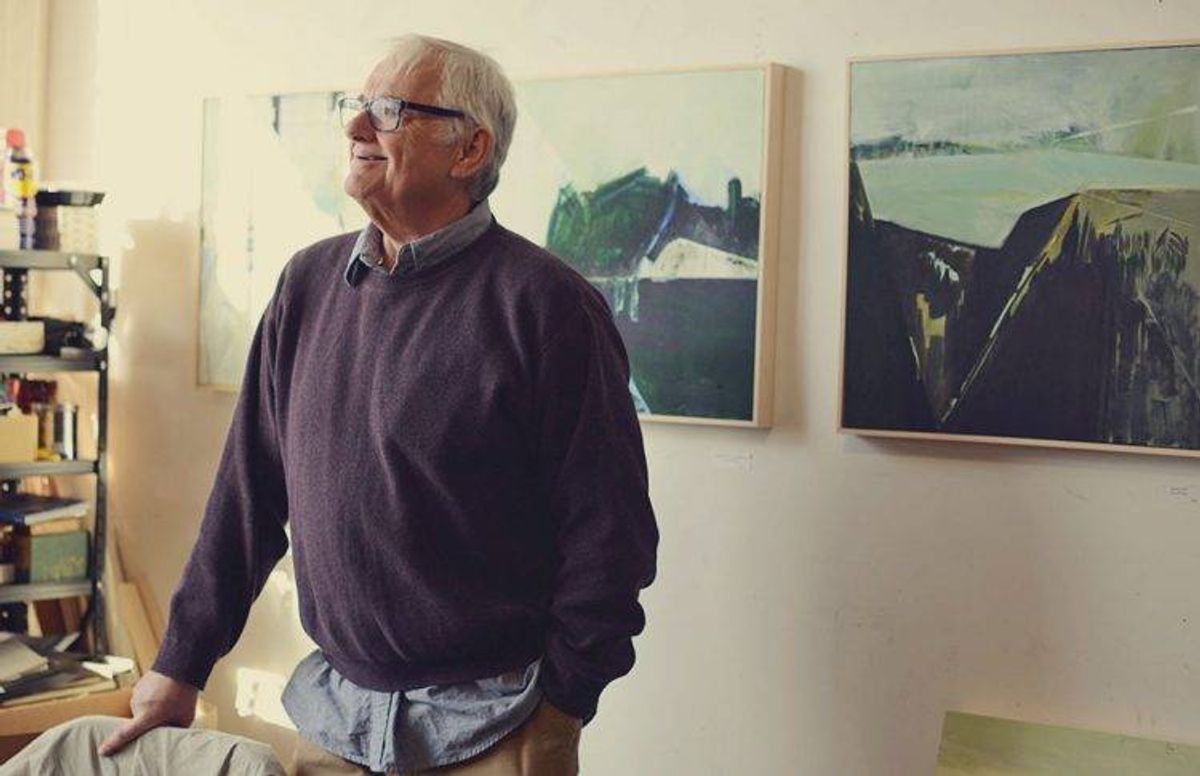

In James Wrayge’s quiet studio on an early winter afternoon, there is a tangible sense of purpose. Wrayge’s paintings line the walls along the portion of the space he shares with another artist at the Northrup King Building in Minneapolis. There are also some paintings on the floor propped up against the same walls. And there is one — in progress — set on an easel in the corner.

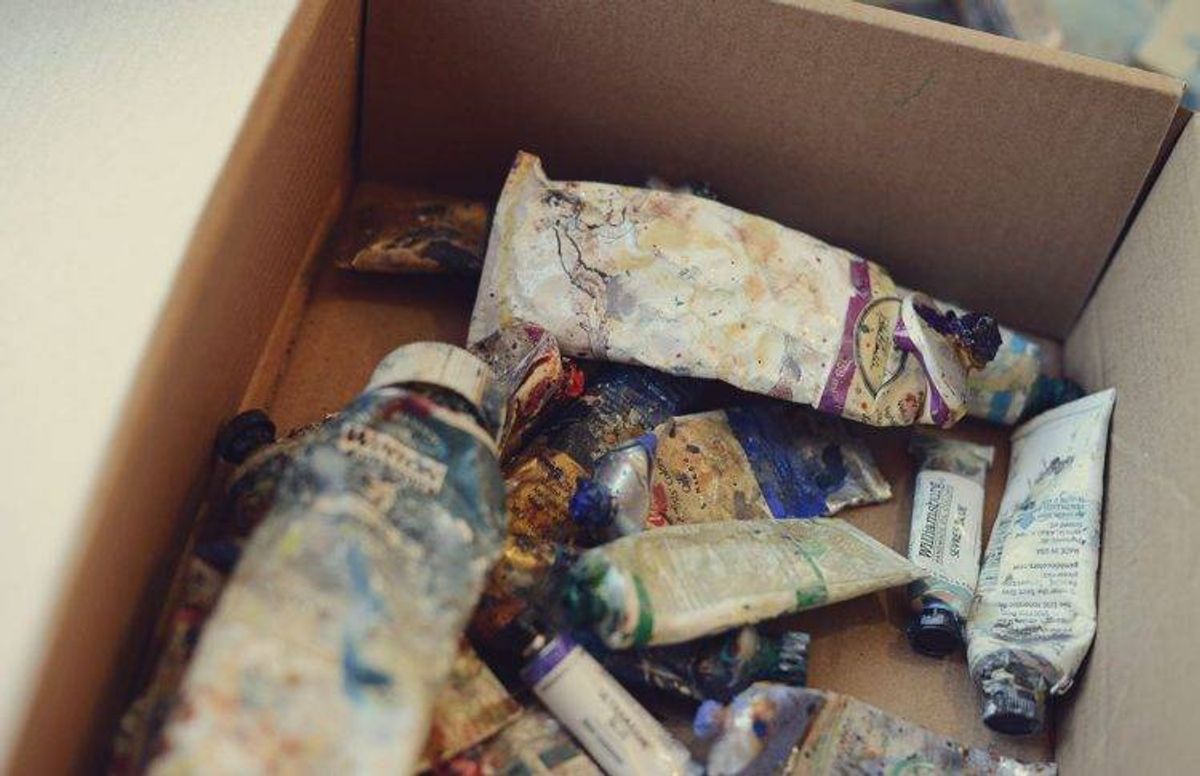

Adjacent to the easel is a large set of windows, a little dusty with age, but still filling the expansive, high-ceilinged room with natural light. A table next to the window bank is loaded with metal cans containing well-used brushes and a variety of paint tubes — primarily oil, many of which Wrayge orders from Belgium, since suppliers there have the types of paints and colors he wants.

“I don’t believe in cheap paint,” he says.

On the table, there’s also a hand mirror, which Wrayge considers one of the most important tools of his trade. “You can look at things backwards, or look at just one half of a painting. It can help bring everything into focus,” he explains.

‘The Imagery Collects in My Psyche’

At this point in his career, Wrayge, 72, focuses on what’s important to him. He knows how much time he wants to spend painting in the studio and how much time he wants to spend in an even more peaceful place, northern Minnesota, where he ventures frequently with his wife, Erica.

“When I’m up north, especially in the winter, the imagery around me collects in my psyche. I don’t paint there, but I always have my camera with me,” he says.

"What I prefer to say [about my paintings] is that they are a visual manifestation of my values."

What else is important to Wrayge is the ongoing relationship between the paint, the canvas and his mind’s eye. But don’t ask him how his work has evolved since he started painting in 1972.

“I don’t like the word ‘evolve,’” he says. “Art means the same thing today as it always has. Styles change, but art doesn’t.”

With that said, Wrayge admits that developing as an artist “is always a growth process” and over the years, he’s become more aware of what he likes and what he doesn’t.

‘Painting Is My Adventure’

Born and raised in Minneapolis, Wrayge attended the University of Minnesota, originally intending to study photojournalism. However, an Introduction to Studio Arts class changed his mind, and his career path. Wrayge juggled his life as an artist with a bartending job for 36 years, finally turning to art full-time in 2002.

Since he was originally drawn to photography, it might seem natural that Wrayge began to paint solely in black and white.

“I still go back to that when my colors aren’t working, or sometimes after winter ends when black and white is still subliminally on my mind,” he says.

Hesitant to put too defining a label on his work, Wrayge claims his paintings have “a landscape feel.” He doesn’t consider them to be abstract. “That’s a word invented by the press, not by painters,” he says. “What I prefer to say [about my paintings] is that they are a visual manifestation of my values."

In front of the easel, Wrayge says he will paint a bit and stop to contemplate what his work means in that moment. “Why do I like that line? Why do I like that color? Each of those questions begs ten more questions,” he explains. “Painting is my adventure.”

Waiting for What Works

Typically, Wrayge arrives at his studio at Northrup King, a collective where more than 350 artists work, at 10:30 or 11 in the morning. He believes the best light is found “around one or two" in the afternoon.

He thinks he tends to be more productive when he’s feeling “a little bit of tiredness,” adding, “when I’m too awake, something just doesn’t work.” The pot of coffee he used to brew in his studio is no more; now he just allows himself one cup before he arrives.

Wrapping up his work for the day, Wrayge generally leaves the studio by 4 p.m. Sometimes that work has involved just looking at the canvas as the day has passed, and all that time, it's possible, as he says, that "I didn’t touch a brush.”

The reason, Wrayge explains, is that while he has the visual elements for what he is trying to capture available in his mind’s eye, sometimes knowing what will work and what won’t takes time.

“You have to wait to arrive there. And sometimes, I’m impatient,” he says, with a slight smile.

Sometimes his patience wears thin. “There was a painting I was working on for a year and a half, almost every day,” he says. “It almost drove me over the edge. But the individual parts of a painting are never important unless the whole thing works.” Finally, that one did.

Wrayge has abandoned some paintings over the years. “I can tell if it’s not going anywhere. And when that happens, it’s not a loss for me,” he says. “Everything I put my name on is an A+ painting, and when I can see it won’t be, I stop.”

During his career, there have been times where Wrayge has completed 40 or 50 paintings in a year; last year, he thinks the number was around 18 or 19.

‘I Want to Spend My Time Painting’

Wrayge has done many commissioned paintings (including a piece for Neiman-Marcus) over the years and laments a distressing trend in the fine-art business.

“Art has become more commodified. People want something quick and fast. And the audience for serious work has shrunk,” he says.

He misses the passionate and knowledgeable art dealers he used to work with frequently. “Now, art is something to sell, like a tire. And you don’t have to know about racing cars to sell a tire.”

For many years, Wrayge sold his work in galleries, but he is less likely to do that now. He’s sold paintings across the world — Australia, China and Europe — and all over the United States. He has a website which features his work, but admits he’s not aggressive enough when it comes to social media and marketing his art online.

“When I get here to the studio, I want to spend my time painting,” Wrayge says.

‘The Thrill of the Last Few Minutes’

As a word enthusiast, I was interested in finding out how Wrayge selects the short and descriptive titles for his paintings (such as "Ask Kafka" and "Frank’s Tango" and "Wolf"). The choices aren’t as complicated or inspired as one might think.

“The title of a painting is really for cataloging purposes; it’s more for a reference. It’s not a definition. Sometimes, the titles make no sense except to me,” he says.

Overall, Wrayge’s role as an artist truly matters only to him, and is not dependent on the whims of the outside world. “As a painter, my needs are simple,” he says, adding that while he’s slowing his output a bit, he’s secure with his identity as an artist and still “not afraid to fail.”

He glances toward the ceiling as he describes “the thrill of the last few minutes” spent with a painting as it nears completion.

“It’s unexplainable, really. It’s a personal and private thing. It’s spiritual and it’s physical,” Wrayge says. “Then there is a big smile on your face and a flutter in your heart when you know you’ve gotten it right.”