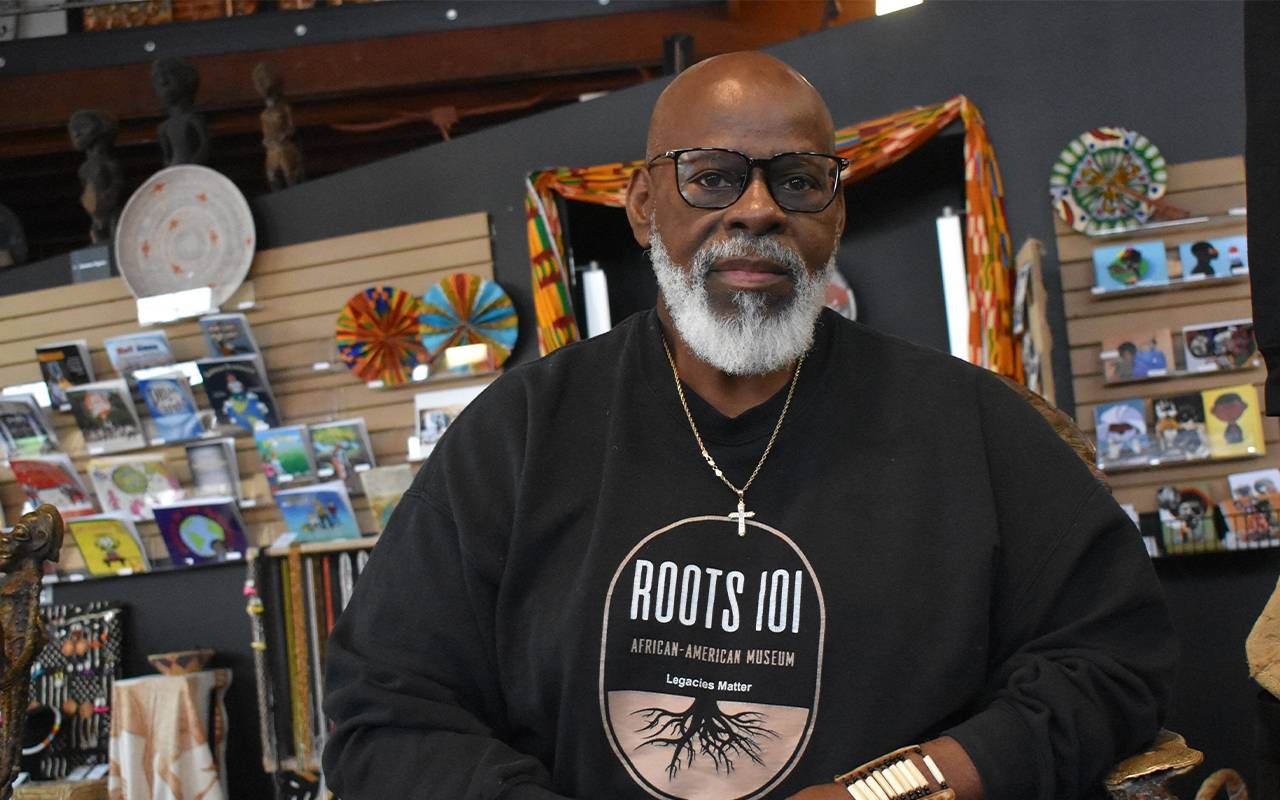

A Kentucky Collector Finds Purpose in His Passion

Lamont Collins' Louisville museum, Roots 101 African American Museum, is a testament to the past and a source of inspiration for the future

When Lamont Collins' family moved to a mostly white Louisville, Kentucky neighborhood in the 1960s, he felt like he'd been dropped behind enemy lines (although he was never physically harmed). He survived and thrived in large part because of his athletic ability, which later earned him a spot on the University of Louisville football team. "I was always the best athlete, so kids would always put me on their team," he says.

"In higher education the first class you take is 101. At the museum, it's an educational journey from Africa to America."

Like sports fans of every age, Collins and his teammates loved to argue about who the best professional athletes were — Sandy Koufax vs. Bob Gibson in baseball, Bob Cousy vs. Bill Russell in basketball, hometown legend Paul Hornung vs. Jim Brown in football. Collins tended to take the side of the Black players like Russell in these arguments, and his white friends would sometimes come back days later and say things like, "I talked to my dad, and he said Bill Russell's pretty good."

"So I found out, like at nine or ten, how important it was to tell our story," Collins says.

Telling Black stories is just what Collins, now 63, is doing as founder and CEO of Roots 101 African American Museum in downtown Louisville. "The reason I call it Roots 101 is because in higher education the first class you take is 101," he says. "At the museum, it's an educational journey from Africa to America."

A Journey of Discovery

The first thing visitors see as they enter the museum is a group of centuries-old sculptures from the Kingdom of Benin, many depicting royal figures, interspersed with paintings of African royalty by local artist Sandra Charles. The placement is intentional — and not just because the sculptures are the museum's oldest artifacts.

"I tell young people that we're descendants of kings and queens that were enslaved in America," Collins says. "And that's a game changer for a Black man like me, because when I was a kid, all we ever heard was that we were slaves and only slaves. But what I tell young people is that we were bulldozers before bulldozers, jackhammers before jackhammers, and engineers before engineering degrees; we built this place."

"That's a game changer for a Black man like me ... when I was a kid, all we ever heard was that we were slaves and only slaves."

From the Benin bronzes, visitors move on to more recent and far less inspirational artifacts: a "Colored Waiting Room" sign atop a Confederate flag, a statuette that's a racial caricature of a jockey, a package of tobacco whose name includes a racial slur. (The curly tobacco evokes images of natural Black hair.) "You see these images of Black people going from looking human to looking like monkeys and apes," Collins says. "That was designed to put in that mindset that we were less than human."

Another gallery, dubbed Big Momma's House, shows how Black families have long countered stereotypes and hateful narratives. A replica of a midcentury living room, it's filled with photos of family members who served in the military, went to college, or entered the ministry. "That's how we learned our history; that was our affirmation because it wasn't put in books," he explains.

Other galleries depict Black contributions to the arts and athletics. "The Great Equalizer room is about Black sports; it's about Black men who were first looked on as men when they started playing sports."

But even those galleries remind visitors of racism and racial violence. In a display evoking Billie Holliday's anti-lynching song "Strange Fruit" a hangman's noose dangles in front of a mirror, challenging visitors to imagine themselves in the story.

Protest to Progress

While you could look at Roots 101 as a history museum, Collins is as interested in the present and future as he is in the past. That becomes clear in the Protest to Progress gallery. At one end of the room are stools from a lunch counter where local teens staged a sit-in in 1968. At the other end is a coffin built by a group of Black and white teens in Louisville after the Breonna Taylor shooting in 2020. The coffin is covered with the names of victims of violence, ranging from Emmett Till to Taylor herself.

"When they gave it to me, they said, 'Mr. Lamont, what are you gonna do with it?'" Collins recalls. "I put a mirror in the casket. And the reason I put the mirror in the casket is I want you to see yourself. I want young people and older people to see themselves in history."

In fact, challenging visitors is what Roots 101 is all about. Collins' goal is to help people become better ancestors. "If we all become better ancestors, we'll be in a better place and a better country."

Turning Artifacts Into Action

Despite his clear vision, Collins never really planned to start a museum. For decades, he was just a collector — albeit a collector with an impressive set of artifacts.

The first item in that collection came courtesy of his mother, who worked at the local Armed Forces examination bureau. When young Cassius Clay — the future Muhammad Ali — showed up at the office, she got an autograph for her son. "That was my first one," Collins says. "And I was hooked ever since."

He first got the idea for a museum in 2018, when he heard an NPR podcast about a California collector, Oran Z, who was looking for a home for some 14 or 15 railroad cars full of Black history from his own museum. Collins quickly called the man, who inspired him to start Roots 101. "Even though he never sent anything, he really energized me because I knew I had at least five railroad cars of history," he says.

In 2021, Roots 101 was named one of the 10 winners of the USA Today Readers' Choice Award for Best New Attraction. It also received plenty of attention that summer when folk singer James Taylor praised the museum during a concert at the nearby KFC Yum! Center. (He had visited before his performance.)

While Collins has enjoyed that notoriety, he's more interested in connecting with young visitors. In fact, the last gallery, dubbed Black to the Future, features photos many of them have submitted. "You see pictures of kids dressed up like doctors and lawyers, aspiring to be whatever they want to be," he says.

"There's an African proverb that says, 'The greatest king plants shade trees knowing he'll never sit up under them,'" he says. "I'm planting trees: trees of knowledge, trees of unity, trees of love, trees of prosperity. I won't live to see the shadows. But I'll plant the trees big enough to cast the shadows."