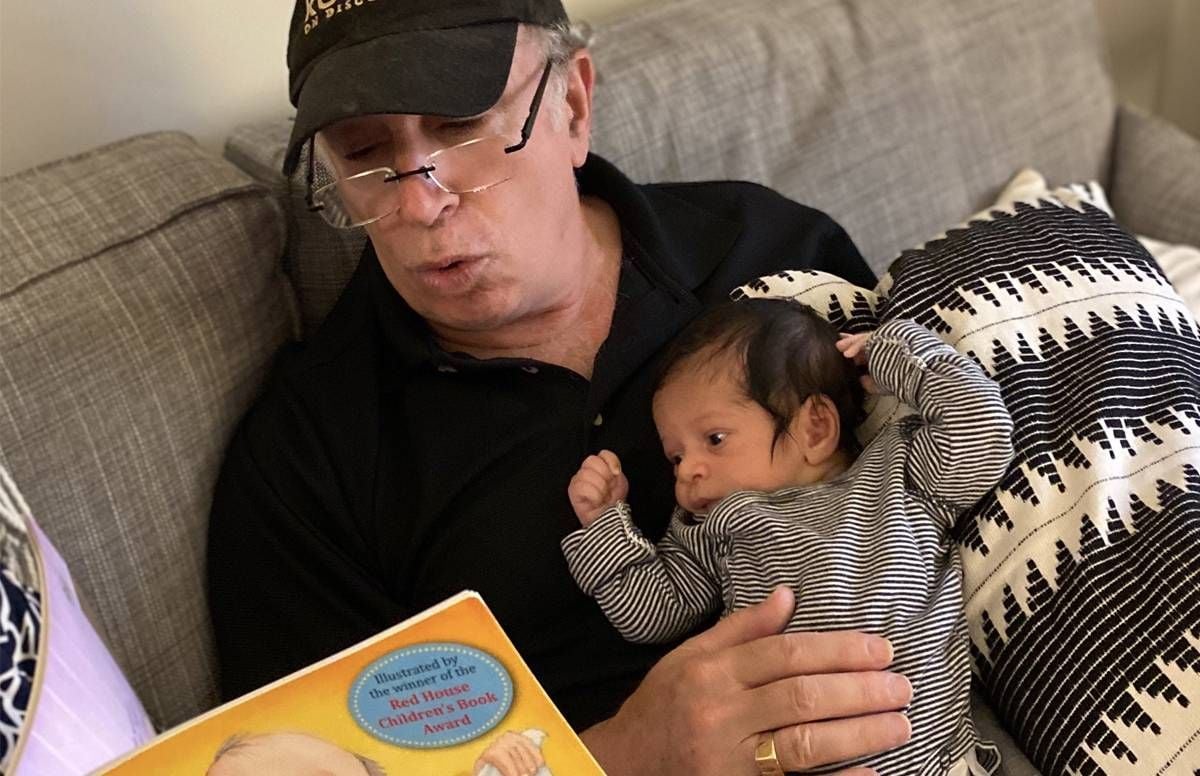

A Letter to My New Grandson

A grandfather reflects on the world his grandson entered in June 2020

Dear Miles,

Since you were born a month ago today, it may be quite a while before you read this.

Your parents have promised to share this note with you at the appropriate time. Think of it as a time capsule: what life was like in June 2020, the month when you were born. Years from now, when you read this letter, I hope you will know what utter joy you brought our family during a tumultuous time for our country and for the world.

You are our first grandchild, so you sit on a special new branch of our family tree. Your arrival came less than two months after we lost my uncle (your great-grandmother’s brother) to a virus called COVID-19, a devastating illness that has so far killed more than a half-million people worldwide, nearly a quarter of them Americans. Your birth serves as a reminder that new life, especially in the midst of a global pandemic, is a blessing.

Your grandmother and I were so excited to meet you that we drove 17 hours from Maryland to Minnesota, arriving in Minneapolis just 36 hours before your birth. When we met you at the hospital entrance the day after you were born, we wore face masks and kept our distance because the virus was very contagious. In that moment, it took everything in our power not to kiss you and hug your parents.

Your birth serves as a reminder that new life, especially in the midst of a global pandemic, is a blessing.

Miles, you entered the world at a pivotal moment in a beautiful city — Minneapolis — but a city that was making headlines around the world for all the wrong reasons. Exactly two weeks before you were born, a Minneapolis police officer killed an unarmed African American man named George Floyd.

Born Into a City During a Difficult Time

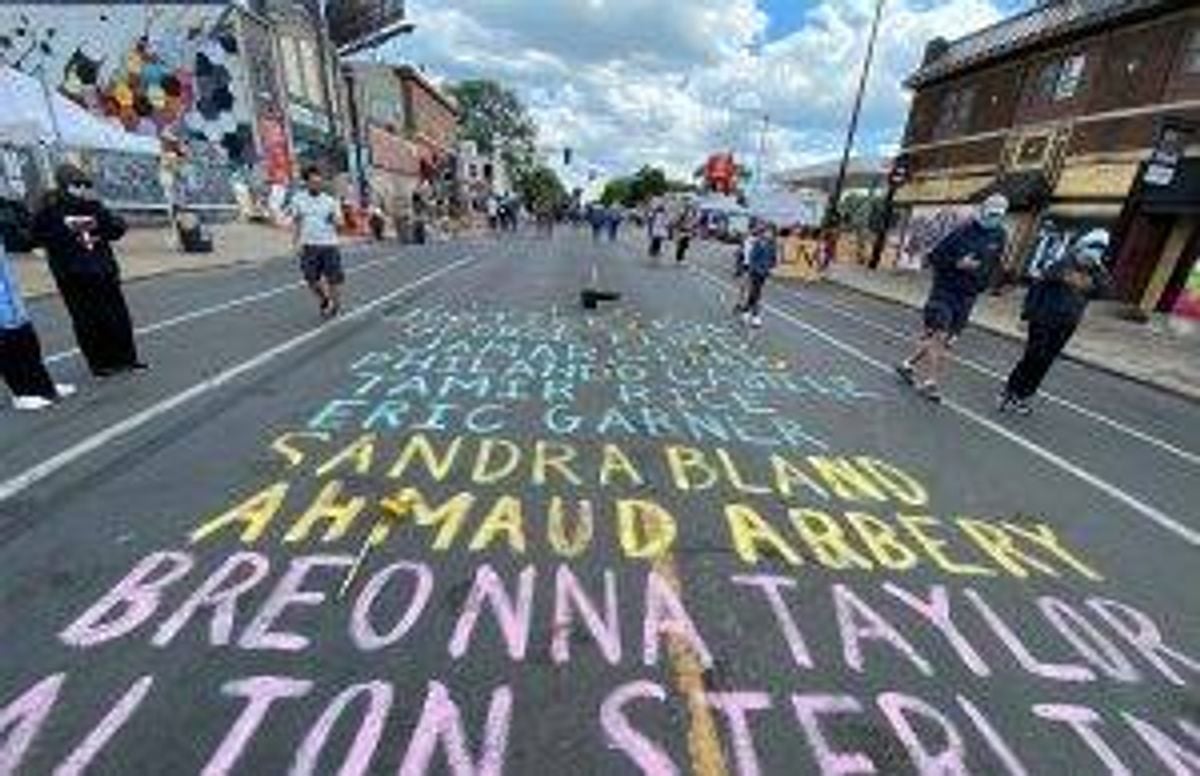

A few days after you were born, your grandmother and I visited the Chicago Avenue intersection where Mr. Floyd was killed. It was still covered by thousands of flowers, left by people who wanted to pay their respects. What really stopped us cold was a block-long list of more than four dozen names painted on the street — memorializing other African Americans who had been killed by police. This week, almost a month later, the list grew to 131 names of people who suffered a similar fate.

As we drove around Minneapolis and walked through different neighborhoods, we were struck by the number of Black Lives Matter lawn and window signs, graffiti and street murals that dotted the city, all honoring the memory of George Floyd.

And there was something different, almost encouraging, about the reaction to that awful moment. The city of Minneapolis woke up, then the country woke up from its slumber. People of all ages, races and backgrounds took to the street. And as of this moment, Black Lives Matter is the largest protest movement in the history of the United States.

By the time you read this, I hope enough progress has been made so you can say you were born at a turning point in race relations. In early July 2020, at least, it feels that way.

During the month you were born, statues honoring Civil War generals who fought on the Confederate side to preserve slavery were taken down in cities across the country. In Minneapolis, the City Council pledged to dismantle its police department, and police reforms were announced in other cities.

Sometimes out of tragedy, Miles, comes lasting positive change. This may be such a time. Our last President, Barack Obama, was the first Black president. Like you, he is biracial and like your parents, his mother was a white American and his father was a Black African. When President Obama was elected, some people spoke about a post-racial society. We clearly don’t have one yet, but perhaps this current moment is ushering in that era.

The Story of Your Family

As a white man who grew up in an all-white Boston suburb, my first meaningful interactions with African Americans came in high school when my town was part of a program that bused African American students from the inner city to our school and then back home at the end of each day. For me, nearly 50 years later, the lasting legacy of that program is the friendship I still have with some of those Black students from the high school track team and the classroom.

As a lifelong journalist, I have had the privilege of telling other people’s stories. During my career at NPR and at ABC News NIGHTLINE, racial divisions in our country and around the world were always part of the human experience we covered. One particular news event may be especially responsible for starting the chain of events that resulted in your parents meeting each other while working in Liberia in West Africa, following that country’s civil war.

In February 1990, when your mom was six years old, she was in a hotel room in Chicago getting ready for her uncle’s wedding. As the story goes, she was watching a special report on TV because I was in Cape Town, South Africa preparing to produce an interview with Nelson Mandela, the famous Black revolutionary who fought against the white South African government’s racial separation known as apartheid. He had been jailed for 27 years. So when Mandela appeared on the TV screen a free man, your mom started jumping up and down, saying “NELSON MANDELA IS FREE! NELSON MANDELA IS FREE!" Four years later, Mandela became President of South Africa.

One particular news event may be especially responsible for starting the chain of events that resulted in your parents meeting each other while working in Liberia in West Africa, following that country's civil war.

I’ve always wondered whether your mom’s interest in Africa sprung from that moment because years later, she spent her junior semester abroad at the University of Cape Town, was part of the Princeton in Africa program and eventually worked in a number of African countries throughout her 20s that led her to Liberia.

Your dad grew up in Nigeria, but spent 11 years in American universities and graduate programs that also led him to Liberia.

Both were doing public health work. They met during their first month in the capital, Monrovia.

Two years ago, months before your mom and dad were married in the United States, our family traveled to your dad’s home country, Nigeria. There, we met your other grandparents and your dad’s siblings and attended an engagement ceremony at the local palace, where your uncle is Chief of the Gbagyi ethnic group.

During our 10 days in Nigeria, we saw so few other white people that I could count them on one hand. Even more amazing, when we visited Kuzhipi, the rural village where your Nigerian grandmother grew up, among those who came to greet our bus load of Americans from Washington, D.C. were young people who had never met a white person. For us, it was a small glimpse into what it’s like to be a minority.

My Hope for You

Miles, by the time you read this, I’m convinced many things will have changed for the better in the United States.

You should know that you were born the week of the 53rd anniversary of the Loving vs. Virginia decision in which the U.S. Supreme Court legalized interracial marriage in our country. Your parents’ wedding celebration took place in Leesburg, Va. and members of your dad’s family traveled from Nigeria to the United States to be part of the festivities, just months after we visited them in Nigeria.

The sharing of cultures is a far better alternative to the racial strife that has plagued this country for much of its history. And as you grow up, my hope is that much of the racial inequities and tensions between the races will be relegated to the history books and not be part of your life experience.

May you and your generation experience the kind of progress in race relations our generation and those before us couldn't accomplish.

By the time you’re old enough to drive, I pray your parents won’t have to sit you down and give you “the talk,” about how a Black person should behave if ever stopped by a police officer or how taxi or Uber drivers won’t pick you up because your skin is a shade too dark. I hope all of that is in the rear view mirror.

More than anything Miles, don’t let yourself be defined by the color of your skin. You can be anything you want to be. You came into this world the product of two cultures. Don’t feel burdened by the events of June 2020. Feel emboldened to keep changing the world for the better. May you and your generation experience the kind of progress in race relations that our generation and those before us couldn’t accomplish.

One last thing, Miles: Soon after you came home from the hospital to start your life, a rare double rainbow appeared outside your window. Your mom lifted you up to witness the beauty of that moment — and now you know that in our family, you will always be the gold at the end of the rainbow.

Love,

Papa