Adapting to Climate Change as the Nation Ages

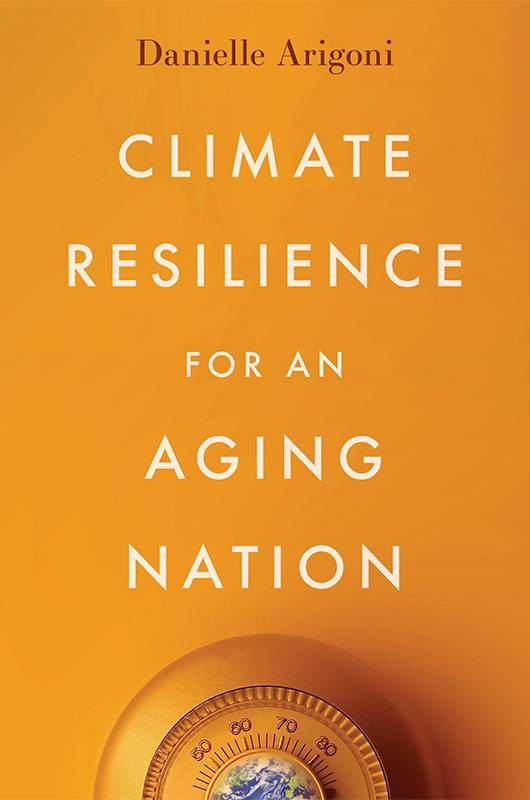

A new book urges policymakers and ordinary citizens to prepare for the effects that a hotter planet may have on the growing number of older adults

It's time for your annual physical. After the usual measurement of weight and blood pressure, the doctor asks what you plan to do if the upcoming summer brings severe heat. She explains how that may affect your chronic diseases.

She then asks what you'll do if a storm cuts off your electricity. How will you power your supplemental oxygen, cool your home, evacuate from your sixth-floor apartment?

Without mentioning the words "climate change" your doctor is taking the warming world into account, and making sure you are planning for its consequences.

Physicians should lead their patients through regular discussions of how their health is affected by the current climate reality. That's one of many calls to action in "Climate Resilience for an Aging Nation," a new book by Danielle Arigoni, managing director for policy and solutions at the National Housing Trust.

Older Adults at Most Risk

The need for such a book is clear. Recent headlines tell the story: "As The Maui Fires Raged, Senior Victims Had to Fend for Themselves." "Millions of Older Californians Live Where Wildfire Threatens." The same message has been repeated from Hurricane Katrina, through deadly heat waves in the Northwest and fatal cold snaps in Texas.

How will you power your supplemental oxygen, cool your home, evacuate from your sixth-floor apartment?

All of these climate-connected disasters have taken the lives of older adults in significantly greater numbers than any other age group. Half of Katrina victims were 75 or older, for example.

Arigoni's new book summarizes the dire news, but offers a clear way forward. To provide comprehensive solutions to the problems of our warming and graying world, she mines her experience at the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Housing and Urban Development.

At HUD, she helped lead a program distributing $1 billion to communities planning for resilience in the face of what the United Nations has deemed a climate emergency. She also cites lessons learned while working on the Livable Communities team at AARP, and her current job at the National Housing Trust.

As Society Ages, Danger Grows

The book starts by spotlighting the demographic shift underway in the United States. As Arigoni told me recently, "We're about 10 years away from a point where there will be more older adults, people over 65, than people under 18, for the first time ever." And, for the purposes of her book, Arigoni says, it's important to note that "older adults are located disproportionately in states of higher climate risk, like California, Texas, Florida and New York."

Other data points to consider? "About one in six, or 15% [of older adults] live at or below the poverty line," Arigoni says, "and only about 4% live in nursing homes or independent living facilities." A large majority live in the community and about one-third of those older adults live alone.

Given those facts, and the continuing climate-change challenges we face, how can we adapt our world so that older Americans no longer bear the brunt of both a hotter planet and more-destructive disasters?

Here's where Arigoni's experience comes into play. In her work at AARP, she led an initiative that encouraged governments, from small towns to states, to view solutions to problems of daily life through an "age-friendly" lens.

Building on work at the World Health Organization, this approach proposes that what leads to a better life for those past the ages of 60 or 65 is good for everyone — in realms like transportation, housing and the built environment, emergency services, work, communications, civic engagement and health services.

Red Flags in Lahaina

For example, when broadcasting instructions for safe evacuation during a disaster, planners often fail to reach older populations. Even when they try, she says, "they often use a very simplistic notion of what older adults are in terms of 'let's think about the folks in nursing homes, check the box, we're done.'"

When broadcasting instructions for safe evacuation during a disaster, planners often fail to reach older populations.

In fact, many more requirements need to be addressed. "The great thing is that when you do that," Arigoni adds, "you're solving for needs that are not just experienced by older adults, but by low-income households that don't own a car, people with disabilities who don't drive, or immigrants who may have limited English."

This brings to mind the situation in Maui, where a "red flag" alert was broadcast to cell phones and the media the day before the deadly fires, warning that conditions were ripe for fast-moving blazes. But that warning wasn't helpful to those who didn't receive or understand it.

Adaptation vs. Mitigation

What the community missed as wildfires swept through Lahaina on August 8 were loud sirens or alarms. And even those would not have helped someone unable to hear them. Arigoni draws the lesson that communication in natural disasters will always benefit from a redundant, "all of the above" approach.

"That means some people were not eating or getting a prescription [because] they're trying to keep their home warm or cool."

In her book, Arigoni focuses on "adaptation" rather than "mitigation," although she's passionate about both. Most of the book's recommendations are about seeking safety for our aging population, and benefits for all, in a world that continues to warm (adaptation), and less about alleviating or reversing human-caused climate change (mitigation).

Luckily, adaptation and mitigation often converge, such as in the necessity for taking a new look at how utilities are delivered and regulated.

In 2018, she tells me, "AARP reported that 17% of low-income older adults went without basic necessities in order to pay their utility bills. That means some people were not eating or getting a prescription [because] they're trying to keep their home warm or cool."

Higher Utility Bills Coming

As weather becomes more extreme, she continues, "those utility costs will keep going up, and will take a significant and disproportionate share of low-income people's [resources]."

Beginning to solve that problem, "whether that means replacing systems with more energy-efficient [options], whether that is weatherizing homes, whether that means integrating renewable energy into homes, all of those things are really important investments in a resilient future, so that people don't have to make those trade-offs between 'will I be able to eat this month or can I keep my apartment cool to survive?'"

The heart of Arigoni's book is her chapter on "Strategies for Age-Friendly Resilience." These range from "Providing Adequate, Affordable, Secure Housing" to "Expanding Transportation and Mobility Options" and "Making Emergency Management More Effective."

If you understand that each of these strategies also stands on its own to create more resilient and equitable communities beyond the focus on aging or climate, you're beginning to see how she approaches the subject, and where solutions will be found.

Ideas Gaining Traction

In her work for both the government and nonprofit sectors, Arigoni's north star has been engaging community members to contribute to their own well-being while enhancing their connectedness.

She said she believes that coalitions of involved government and nonprofit agencies must bring expertise to the table to forge problem-solving partnerships. A recent trip to New York state convinced her that the book's advocacy of these strategies is already finding a receptive audience.

"I was in [Tompkins County] New York recently doing a community meeting and was very, very encouraged to see the exact conversation that I had hoped would occur with this book take place in front of my eyes," Arigoni tells me.

'Let's Get to Work'

"There was the Office of Aging for the county, talking to the Department of Emergency Management, talking to a different organization that runs the sustainability programs to get electrification and energy efficiency rebates into people's homes, sitting next to the person who was from the planning department, sitting next to the person who's the home health care provider.

"And all of them were realizing that they had this connection point among them, that they hadn't fully utilized. And that was, hopefully, the beginning of their being able to serve the residents of this rural county in upstate New York."

Arigoni ends her book with a simple appeal: "Let's get to work." I asked her what she envisioned.

"I guess a couple things. One, examine your own personal risk. Then have a clear idea about what are the risks of living in a place where you're going to continue to confront climate challenges and take stock of whether that's a feasible path forward. . . ."

Get Involved

Active citizens also can "get involved in decision making at a local level," Arigoni says. "If they're not hearing local officials talk about climate change, ask them why not? If they're not hearing their local officials connect the dots between housing policy and social connectedness and climate risk, challenge them on that.

"If they're not getting the kind of support they need to make their own homes more resilient, even if that means just some assistance and some information about how I can reduce my own vulnerability here in my home, ask for those kinds of services. . . .

"When we're pressing on our local officials," Arigoni concludes, "when we're pressing on our community-based organizations, to think more broadly and to think about the connections between all of these elements, we're not just serving ourselves as individuals, but as members of a wider community."