An Afternoon in a Cemetery

In this 'Near the Exit' excerpt, the author invites friends to talk about mortality

On an unseasonably hot day in June when the temperature was forecast to be in the 90s, I packed several bottles of water, snacks and a couple of books on death (conveniently, my shelves are full of them) and drove to Oakland Cemetery in a historic neighborhood of my hometown of Iowa City, Iowa. I would spend the day contemplating mortality.

I hoped to have some company, because the previous day I'd sent an email to a dozen friends with this in the subject line: "An Invitation to Talk About Mortality." I'll be in the cemetery from nine to five, I told them. Stop by if you want to talk about death.

It's an indication of the peculiar nature of my social circle that several people accepted my invitation. (Though another declined with the reply, "Are you kidding? It sounds like a foretaste of hell.") I found a gazebo in the corner of the cemetery where cremains of bodies donated to the local medical school are interred, set up my lawn chair, got comfortable and started thinking.

These sorts of conversations come naturally in this setting, I realized, as we begin to contemplate joining our comrades buried around us.

Despite the heat of the day, a breeze kept me relatively cool. Periodically, friends came by and we talked. But mainly I simply sat and observed the quiet rhythms of life. Occasionally a jogger ran past. A couple of teenagers whizzed by on skateboards. A pregnant woman walked slowly past me, her large stomach silhouetted against the gravestones behind her.

Late in the day, an elderly woman drove up and took out a watering can from her trunk. She filled it at a hydrant, then hauled it to a grave near her car and watered its flowers. She repeated the process three times, her methodical movements giving me the impression she'd done this many times.

Fruitful Places to Study History

Historian Loren Horton had told me that graveyards are fruitful places to study history — each part of them has something to teach us, he said, from the design of the entrance gate and style of landscaping to the shape and type of material used for markers.

For example, slate was common in eighteenth-century New England because it was often locally quarried and easy to carve. Farther west, limestone predominated. The Victorians favored marble, though bronze and iron were also popular.

Today, the most common material is granite, which withstands weathering better than marble and can be easily etched with machine or laser tools. Finely detailed portraits are now the fashion in many locales. Once only the very wealthy could preserve their image for eternity; now it's a middle-class option.

The Victorians used a wide variety of symbols that once conveyed a great deal of information to passersby, though we've largely lost the ability to read them. An intact column means that the deceased lived to a ripe age; a broken one indicates that the person died prematurely. Crosses come in many variations that indicate denomination and ethnic background, from the Greek cross of the Orthodox to St. Andrew's cross for those of Scottish descent. Lambs adorn many tombstones for children, while a dove carrying a rosebud in its beak means that an infant rests beneath the marker.

Meaningful Epitaphs

As I strolled through the cemetery that day, I explored my personal history as well as that of the community. I found the grave of the surgeon who'd repaired a hernia years ago ("my guts are still minding their p's and q's, thanks to you," I told her) and the grave marker of the ex-husband of a friend. I remembered the afternoon when we gathered to bury his ashes, recalling the low roar of his motorcycle-riding friends as they showed up to honor him and the feel of dirt in my hand as I threw a handful of soil onto the box containing his remains.

I saw the monument for a former landlord, surprised to see that next to it was the grave of his ten-year-old daughter. During the years I lived in his apartment, I didn't realize the sadness that he must have carried within him.

Even if I didn't have a connection to the deceased, I read the epitaphs with curiosity. Loren had said that in the colonial era, they often served as a warning to the living: "As I am now so shall you be; prepare for death and follow me" was a common cheery message, for example. Most of the ones I saw that day didn't bother to sermonize, but simply gave a few details about the person's life. When you're paying for chiseled words on marble, you don't want to get too chatty, and terse Mother, Father, Husband and Wife were most common.

But I spotted more unusual descriptors as well.

One woman was buried beneath a stone marked "Professor." Another couple wanted to make sure that passersby realized they weren't from around here: "Born in Germany," it said under the man's name, and "Born in Brooklyn, New York" under the wife's. No mention of where they died, but I guessed they were disappointed if they breathed their last in Iowa City.

Cemetery Conversations

Back in my lawn chair once again, driven into the shade by the growing heat of the day, I was happy to have a friend show up. For an hour, Wendy and I talked about growing older. Recently retired, she was struggling to find a new identity now that she was no longer employed. She spoke of how difficult it was to sort through the boxes of books and papers she had accumulated in her career and how she was debating where she would live in advanced old age. These sorts of conversations come naturally in this setting, I realized, as we begin to contemplate joining our comrades buried around us.

An hour later, William showed up and told me that during part of his childhood, his father was a mortician. They lived in a funeral home — a detail that I hadn't known despite being friends for years. It made him comfortable with death, William said, and contributed to his decision to become a physician.

Next came Jody, arriving by bike despite the heat. She shared the story of a letter she received from her mother a year after she died: it was in her mother's handwriting, she recalled, and had been mailed a few days before her death. She thinks it must have slipped into some nook or cranny in the nursing home and been mailed by a staff member once it was discovered. She described the moment it arrived and the sense of unreality as she received a message from the Great Beyond.

"In the letter she told me how much she loved me," Jody said, blinking back tears.

"Maybe it really did come from your mother after her death," I said.

We sat in silence as we pondered the mechanics of how the dead might communicate with the living — a natural thing to ponder, there in the cemetery.

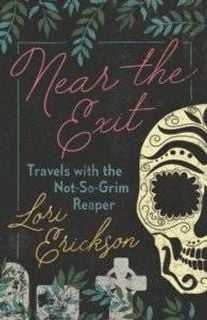

Excerpt from Near the Exit: Travels with the Not-So-Grim Reaper (Westminster John Knox Press)