An Insider's Guide to Art Festivals This Summer

What to know before you go, including how art festivals are adapting in a pandemic world

In our early thirties, my husband and I met a talented landscape painter in our hometown of Chattanooga who led a seemingly idyllic life: Eight weekends a year, he and his wife packed their van with his paintings and drove off to exotic locales (Miami, Chicago, Denver) to set up a booth and sell his wares. They always came home exhausted, but with a fistful of cash and plenty of time to rest before they had to go do it again.

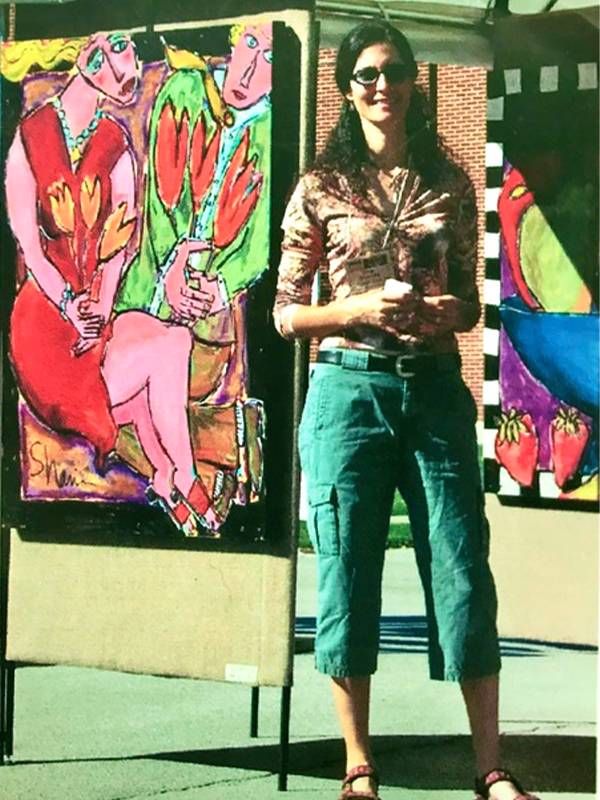

I looked at their lives and felt a deep sense of missing out. So, I decided to change my life. I enrolled in pottery classes at the local community college, and when I had enough pieces, drove to Dalton, Ga.— not exactly an exotic locale, but I had to start somewhere — and set up on the sidewalk beside 50 other artists.

Outdoor art festivals were cancelled last year due to COVID-19, but this year many are returning with safety precautions in place.

I received a merit award and made enough money to quit my job at the mental health center. For the next 20 years, I traveled the country selling my pottery, and later, paintings. A few years later, my husband Daryl Thetford quit his job and followed me onto the art festival circuit, where he sells his photo collage work.

How Art Festivals Are Adapting in a Pandemic World

I tell you all this because it might help entice you to visit an outdoor art festival this summer. Such festivals were cancelled last year due to COVID-19, but this year many are returning, with precautions in place.

"We are focused on ensuring the safety of our community," said Tara Brickell, executive director & CEO of CherryArts, which runs the highly rated Cherry Creek Art Festival in Denver.

To that end, it's moving to a different location in the city, so show administrators can control the flow of patrons. That's a commitment embraced by other shows as well.

Some, like the Park City Kimball Arts Festival in Utah, are cutting back on the number of exhibiting artists, to allow for more space between tents and better circulation. Others, like the Bayou City Art Festival in Houston, are moving their show to later in the year to allow more time for more festivalgoers and artists to get vaccinated.

And still others are doing all of the above. To see a particular show's safety protocols, log onto the festival website before you go.

Everything You've Always Wanted to Ask Festival Artists

With many people excited to look at and shop for art again, I thought it would be helpful to offer an insider's guide to festivals, to enhance festivalgoers' viewing experience and to give a look under the hood of this thriving economic vehicle that, at its heart, is powered by soul.

Read on for my answers to the questions artists get asked most frequently.

Do you just do this for fun?

Shows are, first and foremost, economic endeavors, both for the cities that host them and the artists who participate in them. Festivals generally pay to take over the recreational area, shopping center parking lot or town square where the show is held, or secure permission from the city to overtake city streets and curtail or redirect the flow of vehicle traffic.

While there are artists out there who feel the marriage of art and money to be an uncomfortable union, most of us don't have that luxury.

Very small shows may have as few as 50 artists and bring in only a few hundred patrons. But larger, more prestigious shows feature several hundred artists spread out over multiple city blocks and boast attendance in the hundreds of thousands over the course of two or three days.

Shows put money in the coffers of the cities that host them; bring people out to shop and eat; bring tourists to the city; are welcome social opportunities; bring affordable art to the public and often offer additional activities such as musical acts, educational opportunities for children and culinary demonstrations.

In answer to the question, do we just do shows for fun, the answer is, we hope not. Because while it can be fun to be an exhibiting artist, it can also be grueling. We often drive hundreds of miles to get to a show, set up our booth in every kind of weather and spend long hours on our feet talking to festivalgoers about our art. We are there, first and foremost, to make a living. Which brings me to…

Can you actually make a living doing this?

We're all familiar with the term "starving artist." It connotes a romantic image of the artist as a kind of martyr, pursuing art not for monetary gain but for the sole benefit of self-expression and enrichment of society. While there are artists out there who feel the marriage of money and art to be an uncomfortable union, most of us don't have that luxury. While we love to create art, we must sell it in order to pay our bills.

When I was a potter, I was elated to make $1,500 in a weekend. Figure in the weeks it took me to build up my inventory, the cost of my materials, my booth fee (what artists pay for the spot we are given to set up our 10'x10' show tent; anywhere from a few hundred to a few thousand dollars), gas to the festival, lodging and the cost of meals eaten on the road, and it's easy to see that it takes several $1,500 weekends to make a living doing shows.

Artists must therefore maximize profits. Sometimes, this means creating work in a medium that commands more money (oil instead of acrylic painting, for example, or large-scale work instead of small). Sometimes, it means seeking out the higher-end shows in neighborhoods where the clientele is more affluent or more well versed in the value of original art. And it means knowing the going rate for work in your medium, making sure your prices are on point.

Art festivals can be extremely lucrative: According to Tara Brickell, the 265 artists at the Cherry Creek Art Festival reported over 4.1 million in sales in 2019, or roughly $15,000 per artist. And while the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that in 2020, craft and fine artists made on average about $50,000 per year, I know artists who routinely make $50,000 (and up) per show.

Did all of these artists go to art school?

While some artists on the festival circuit have art degrees, many had non-art-related identities and careers prior to becoming artists.

Beverly Hayden, a Chattanooga-based mixed media artist, was a lawyer before she turned to art. Trés Taylor, a Selma, Ala.-based folk artist, was a biochemist. Greenville, S.C.-based artist Genna Grushovenko, who with his wife, Signe, paints nostalgic images of days gone by, was a trumpet player in the Ukrainian army.

In general, if you show genuine interest in the art and the process, artists will bend over backwards to answer your questions.

Other artists had first careers as graphic designers, therapists, engineers, medical professionals and almost every other field you can imagine. Some continue to work in them at the same time they're working the festivals.

How are artists selected for a festival?

Shows worth their salt are juried; depending on the size and prestige of a show, an artist can be competing for a spot against hundreds of others in their medium. Most shows use an online application system; artists pay an average of $50 (per show application) to upload four to five digital images of their work and one of their booth presentation.

Three to five jurors — usually a mix of gallery owners, professors, museum curators and other artists — view the slides over the course of one to two days and make their selections based on quality and originality of work, consistency, execution and booth presentation.

Because the jurying is done anonymously, artists with enviable resumés, who command large sums of money at shows or both have no advantage over anyone else on the circuit when it comes to being selected.

Is art bought on the street a good value?

There is an in-depth conversation to be had about what makes art of value — or what makes art art, for that matter. But that is outside the scope of this article.

To the question of whether art bought at a festival has value, however, the answer is twofold.

If the art has value to you, the buyer — if you like it, if it speaks to you, if you will enjoy living with it —then it has value. If you need credentials behind your art, many artists have impressive resumés they would be happy to discuss with you that list exhibits in prestigious galleries or museums; some can tell you about how their work is in the collections of important people.

Some festival artists will become highly successful, and their prices will go up. But even art by famous artists is subject to the whims of a fickle culture. And what is worth a lot during one zeitgeist can lose its value in another.

In general, buying art as an investment — that is, with an eye toward reselling it — is an extremely risky business for the layperson. Even if the art does escalate in value, you would need an art dealer to broker the sale for you, to whom you'll pay a hefty fee. Better to buy the art you like simply because you will enjoy it.

Should I haggle?

Whether or not to haggle is up to you. Some artists will take offense; others will work with you on a price. But an art festival is not a flea market, and artists understand the market value of their work and their time.

"Can I get two for the price of one?" suggests you might be uninformed about the value of art. But a friendly, "Is there any wiggle room on the price?" can open the way for a meaningful conversation about why the work is priced as it is, and possibly a slight reduction.

What question should you ask?

All artists welcome questions about their work. It's always fine to ask about their process, their inspiration, how long they've been doing art and whether the pieces you are looking at are one of a kind, limited edition or unlimited prints.

It's also fine to ask where else the artist shows their work, how it will hold up in various conditions and whether they allow refunds or exchanges (these are rare).

In general, if you show genuine interest in the art and the process, artists will bend over backward to answer your questions.

How to Buy Art

You've heard the adage, "Don't buy art to match the sofa." Most artists will tell you to buy what you love, not what you think you should buy or love. Your taste in art is uniquely your own, so honor it!

"Years ago, choosing a wine seemed a bit scary to those of us who felt we needed to have taken a class in order to buy and drink it," says artist Beverly Hayden. "Now, everyone is drinking wine. We're not intimidated anymore. Sure, there's a lot to learn about it if you desire, but it's also fine to buy a bottle in the grocery store because the label or name looks cool, and just drink it that evening."

Hayden continues, "I would encourage people to approach art the same way. Go to shows, walk around and see what strikes your fancy. Trust your instincts. If it's speaking to you, there's some element of it that will work with what you have. And as your collection grows, the eclectic nature of your pieces will actually work in your favor to create that unique tapestry of 'you-ness' throughout your space."

8 Top Art Festivals

Google "America's best art festivals" and you will get many lists with little overlap. This is because "best" is not a standardized concept.

Below, in alphabetical order, are eight artist-favorites — shows that are difficult to gain entry into, that consistently feature the country's best fine artists and fine crafts people and that bring out knowledgeable and eager art buyers:

Art in the Pearl, Portland, Ore.

Bayou City Art Festival, Houston

Cherry Creek Art Festival, Denver

Des Moines Arts Festival, Des Moines, Iowa

Kimball Arts Festival, Park City, Utah

Old Town Art Fair, Chicago

Plaza Art Fair, Kansas City, Mo.

St. Louis Art Fair, St. Louis

Read More