Breaking Up (With my 212) Is Hard to Do

A 212 number once had a certain cache, a status symbol that indicated we were original New Yorkers. Not too much is original anymore.

The Verizon repairman clomped through my living room, searching for ancient telephone wires to bring my landline dial tone back from the dead.

"You're the only one in the building who still has a landline," he marveled. "You oughta upgrade."

We — my 212 number, not the repairman — and I have been together for 40 years.

In less than half a century, we dialed seamlessly from touch tone phones and Rolodexes, pay phones, services answered by humans and then by machines, cordless phones and now cell phones.

Loud rings jolted me out of bed for news of the death of a friend's brother in a car accident, my great-aunt's downstairs neighbor ordered me to come quickly "she fell and broke her hip" and my accountant reassured me that no, I don't owe the IRS $8,000, they owe me.

Hours of conversations, debates, promises, advice, arguments, remonstrations, sighs, crying and laughter from a beige plastic touchtone rented from AT&T when a call cost 17 cents a minute.

"It's a Manhattan number It's a rare number. Once upon a time everyone was a 212."

For privacy's sake, I registered my name with Ma Bell as A Schulman. As the years went by, it became clear that A meant Any. Calls came in for Arnold. Amy. Andrea. And even for those whose names didn't begin with an A.

"No, there's no Francine here."

Or the caller would ask for the man of the house. How quaint. I've been paying my own bills since I was 19. "Speaking!" I would yell and slam down the receiver.

My 212 number and I first connected via copper cable on the third floor of my apartment building. The kitchen was so narrow that the oven door hit the wall when I opened it to retrieve sweaters stored there. When the widowed Mrs. Zachs on the sixth floor died, the landlord approved my request to move on up where there was enough space to open the oven door.

The Cache of 212

A Verizon rep did the math for me: Two years on the third floor and 38 on the sixth. She thanked me for being such a long-time customer but didn't offer a discount.

If it weren't for the telephone, first patented by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876, we would have been deprived of actress and comedian Lily Tomlin's Ernestine, a nosy switchboard operator whose started out her calls with a nasal "one ringy dingy, two ringy dingy" and a "gracious good morning to you."

A 212 number once had a certain cache, a status symbol that indicated that we were original New Yorkers. Not too much is original anymore.

Until 1984, a 212 number covered all five boroughs of New York City. Talkers in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island and the Bronx were united in slamming the heavy plastic receiver with a certain satisfaction into the base of the phone when hanging up.

"It's a Manhattan number," says Manhattan Borough historian Rob Snyder who still has a 212 landline dating back to 1987. "It's a rare number. Once upon a time everyone was a 212."

These days, though, you can be in Wichita or Minneapolis and have a 212 cell number. 212s become available after someone relinquishes their number by dying, going out of business or giving up that number.

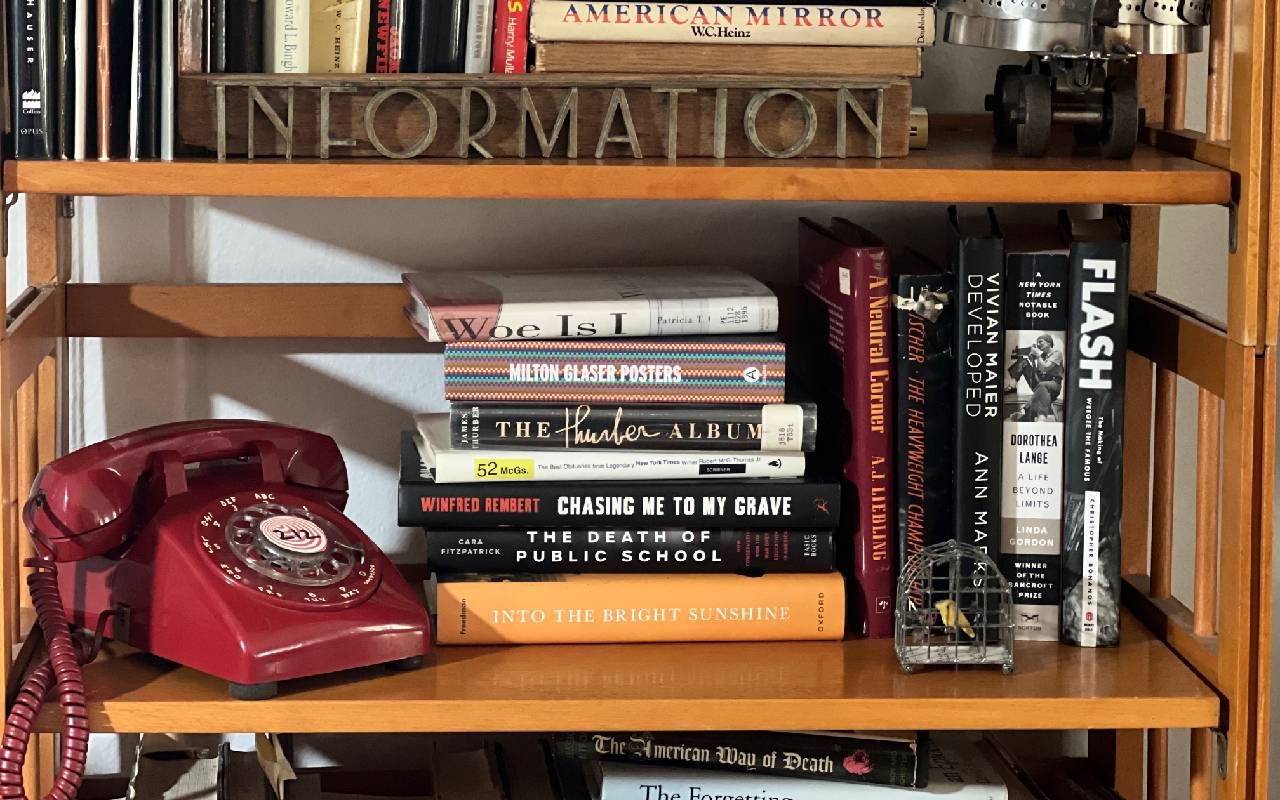

As technology advanced, the demand for Rolodexes, little black books, telephone books given as gifts and telephone directories declined. Touch tone phones began replacing rotary dial phones in the late 1970s. I still have paper telephone books with handwritten entries of family and friends. I don't need these any more. I can add contacts into my phone.

My grandfather's small AT&T telephone book, its cover smudged with fingerprints and pages loose from its binding, held a secret. He rewrote names of relatives, friends and celebrities in pencil over and over again as he struggled with his memory.

Touch Tones, Pay Phones and More

I even go back to the rotary phone when we had one of those ubiquitous beige wall phones in our kitchen when I was in high school. My mother added a lock which I quickly learned how to pick because my best friend Barbara and I had a lot to say. Our hours-long conversations were so important that I can't recall anything about them. And we lived about 15 minutes apart.

Younger generations missed out on shrink wrapped bundles of three inch thick white pages and yellow pages dropped off in building lobbies. Way back not so long ago, caller I.D. was a big deal.

When answering machines became widely used, my great-aunt in the Bronx left me messages that began with throat clearing and ended with "Have Arlene call her Aunt Esther. Do you hear me?"

I stationed myself in a phone booth in Fifth Avenue's Lord & Taylor department store, with rolls of quarters and the help wanted section of the New York Times.

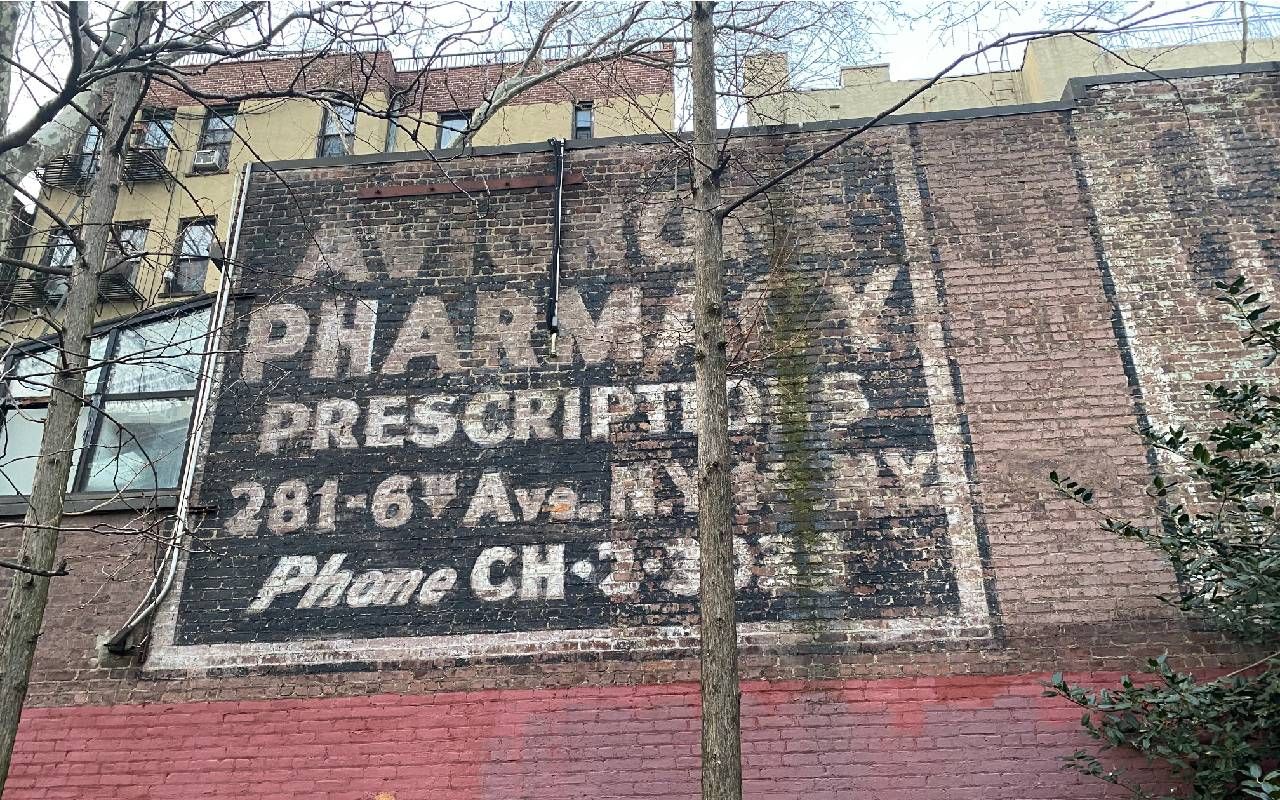

For calls outside of your home, metal pay phones in booths stood on street corners, in the lobbies of office buildings, hung on walls of businesses and were clustered in transit hubs including Grand Central Station.

The receivers often smelled like the previous user's bad breath or cigarettes. Business people, reporters, bookies and drug dealers commandeered phone booths as free office space, depositing quarters, dimes and nickels and waiting for calls to come in.

When I was job hunting way back when, I stationed myself in a phone booth in Fifth Avenue's Lord & Taylor department store, with rolls of quarters and the help wanted section of the New York Times. I wasn't the only one.

Phone booths often had doors that closed for privacy. But the subject of privacy on the telephone is a debatable one. With a very long telephone cord, you dragged a landline phone into a bedroom or bathroom. For family members to hear news, the telephone was passed around with the caller repeating the information to each person.

I can't remember my passwords but I can recall my grandmother's landline in the Bronx that began with KI for the Kingsbridge telephone exchange.

And to save money, friends rang twice and hung up, the signal to call back on your dime. With cell phones, callers talk openly and loudly on cell phones in public places. A much older friend was horrified to hear the details of a stranger's abortion.

While I'm not one of them, hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of panting took place on phone sex lines at $1.99 a minute. Police call boxes were on the street, not in cars. Calls came into candy stores and college dorm lobbies before apartments had individual telephones.

The Pennsylvania Hotel once had what is considered the most famous telephone number in the world. PE6-5000 was immortalized in song by Glenn Miller and his Orchestra and the Andrews Sisters. The hotel closed permanently in April 2020 and demolished in 2023 in spite of attempts to preserve it. The fate of the number is unknown. A rep for the developer did not return my call.

I can't remember my passwords but I can recall my grandmother's landline in the Bronx that began with KI for the Kingsbridge telephone exchange. I dialed the number recently. A recording announced that it was a nonworking number with the NYC Department of Corrections.

And telephone numbers spelled out words making them easy to remember:

1 (800) M – A – T – T – R – E – S, and leave off the last 'S' for savings!"

1 (800) FLOWERS.

And after hearing the singsong radio commercial for 1-8-7-7 Kars4Kids. it stays in my head for a couple of hours and I don't even own a car.

So when Verizon mailed a postcard that alerted me that 5G service is here, I decided that this would be a good time to part with a relic of my past and save $100 a month. Through early 2024, my internet service was connected through my 212 landline. It was so slow that I could take a nap when uploading or downloading videos. There are no plans to wire my building with fiber optic cable any time soon.

An ad for AT&T Fiber popped up on Amazon Prime Video while I watched episodes of "Schitt's Creek." I thought AT& T was going into the business of digestion. Then I realized that it probably means fiber optics.

Emotional Attachment to 212

But could I pull the plug on a 212 number and a landline that carries so many memories?

I'm nowhere near having the oldest 212 number. Manhattan resident Lois G. Baker has been a 212 since 1968. That's 56 years. She is 90 and has a touchtone phone, a cell phone and an Apple watch.

"You have to be home to answer your 212 number. People would be rushing home to wait for a call or you had to call from work."

"You never know who will call. Maybe a reconnection or a miracle phone call. But this hasn't come yet. No old boyfriends. Of course," she added, "They may not still be alive. I'm sentimental. But it would be cutting a tie from my old life if I got rid of it."

Tony Lopez, 54, the owner of several UPS stores in Manhattan, transferred the family 212 number to his cell phone for nostalgia's sake.

"There's an emotional attachment. It reminds me of my childhood," he said.

His father, bored at work, discovered that their telephone number translated to words. "My friends remembered it and it was easy to reach me. Imagine hearing from someone way back from your past," Lopez said. "But I haven't received a phone call in 20 years."

Secrets? There were none.

"You would talk on the phone and your sibling would be on the phone. There was no privacy," recalled Lopez, who shared a bedroom with his younger brother and his grandmother. "'Get off the phone!' Everyone was listening to your conversation."

Early days of the internet called for a modem with a loud grinding sound.

"The things we've been through!" Lopez said. "If I was on the internet you couldn't use the phone. Those were the struggles."

Hattie Thomas of Harlem, who admits to 80 and nothing more, still lives with her 212 landline. She gives it out, but only if she wants to hear from you. A retired budget analyst with the NYC Department of Social Services, she's been a 212 for 60 years.

"The average person doesn't call me," she said, protective of her privacy. "You have to be home to answer your 212 number. People would be rushing home to wait for a call or you had to call from work."

"Death is the saddest call you can get," she added.

An operator once picked up the telephone when you dialed 411 for information. I pressed the numbers on my cell phone to see if it still worked. The operator was as surprised as I was.

"Yes, you can still call for information," she advised with a tone that sounded like Lily Tomlin. "How can I help you?"

I'm still deciding.

"The fascination with 212 is the product of great changes" remarked Snyder, the historian, "when the Empire State Building was the tallest building in the city, when the skyline changed and stores like Lord & Taylor are gone. The yearning for a 212 is a sense of discomfort with the way the city has been changing. New York City was always about the future, a place where people came from elsewhere to start over."

I can't bring myself to do it. I'm keeping my 212 landline.

And I'm actually not the only one in my building who has one, I discovered. At least three other neighbors have them, ready for an emergency when cell phone service has a shutdown.

In an ode to nostalgia, I purchased a red rotary dial phone on eBay for $40 and change. It sits on my bookshelf, waiting for another call for A Schulman to come in.