Ways to Cope When Vision Loss Changes Your Life

The services and experts who can help you live independently

In 2012, Tony Owens began having trouble seeing out of his right eye — his good eye.

He had lost all of the vision in his left eye during his late 40s, but the Ormond Beach, Fla., resident had been getting along pretty well with one eye. He was able to drive just fine, and doing well at his job as manager of direct-mail services at a customer fulfillment company.

Now, at 56, his ophthalmologist told him that glaucoma and optic neuropathy in his right eye had progressed to the point of making him legally blind. He could no longer drive and eventually had to leave his job because he could no longer see his computer screen.

That year, he continued to gradually lose sight in his right eye. "I can tell you that every morning, I would go into my kitchen and open my blinds and look out the window, and I would see my next-door neighbor's house. I just watched that every day get dimmer and dimmer and dimmer to the point where I couldn't see the house anymore," says Owens, now 64. By 2013, he could only sense differences in light levels, and that's the way his vision is today.

Owens has been through major life changes since 2012, including losing his mother, who died in 2013. He had been her caregiver while dealing with his progressing vision loss.

"A lot of patients are told in eye exams that nothing further can be done, and interestingly enough, something further can be done."

"I was extremely depressed after losing my mother and then not being able to work and …. it was just really, really bad. And not knowing what I was going to do. I mean, I was just sitting around the house, doing nothing," he says.

Fortunately, Owens made an important connection in 2013 to the Center for the Visually Impaired in nearby Daytona Beach, Fla. The nonprofit's Division of Blind Services has been a big help, providing him with crucial training in daily living, connections to others with impaired vision and preparing him to be able to go back to work. He now works at the reception desk of the Goodwill Job Connection Center in Daytona Beach.

Owens suffered another big loss in 2019 when his wife died from kidney disease. He says life hasn't been easy, but he is grateful for the help he's received from the Center for the Visually Impaired. He's now thinking of retiring.

Getting Connected with Helpful Services

An estimated 3.4 million Americans age 40 and older are blind or have a visual impairment (a visual acuity of 20/40 or less), according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The most common diseases are: glaucoma, macular degeneration, cataracts and diabetic retinopathy (See photo simulations of how these diseases affect vision).

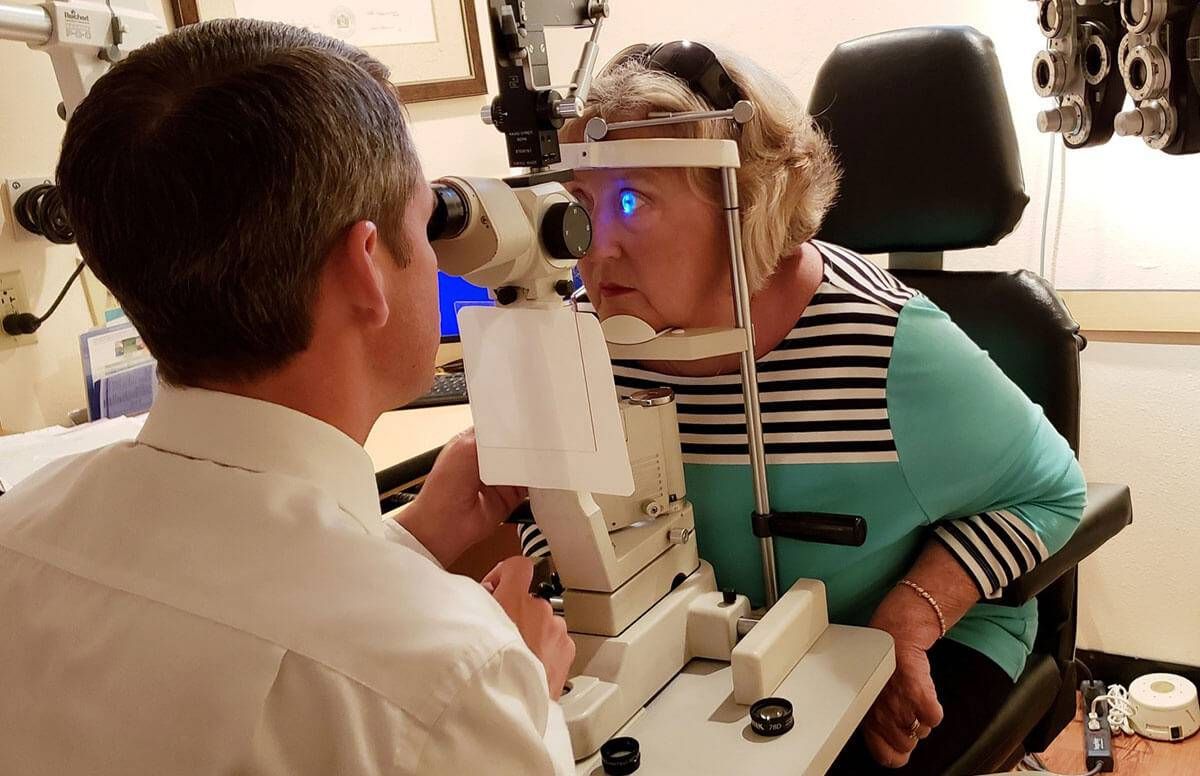

Organizations like the one Owens found give people hope and help them adjust to a new reality with impaired vision or blindness. Also helping people with this are low-vision specialists, eye doctors who offer special lenses and technology to help people function with their visual impairment.

Yet, just 2% to 3% of Americans 55 and older who could benefit from these services seek them out, says Neva Fairchild, the national aging and vision loss specialist at the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB).

"That means the other 96% or 97% are sitting there doing nothing, because either, A, they don't know (the services) exist — that's usually the biggest problem — or, B, they haven't made that attitude adjustment to, 'Well, this is the hand I've been dealt, I've got to learn to play it'," Fairchild says. "They're struggling to do certain aspects of life, whether it's reading or driving or taking their medication properly, cooking meals and other things … and that's just horrible."

Fairchild, 63, who lives and works in Dallas, has lived with low vision most of her life due to a genetic eye condition. She has more than 30 years of experience in the field of vision-loss assistance. Her expertise is in helping older adults find the knowledge, training and technology they need to help them adapt to their low-vision conditions so they can live as independently as possible.

Fairchild says there are many ways organizations and services for the visually impaired and blind can help, including with easy tips and tricks to make daily living easier.

Changing a person's home environment is one way.

"One of the things people do to change their house is an easy furniture arrangement so the furniture is sort of squared off and there's not all these funny angles — so they can walk a straight line and know there's going to be a clear pathway. It can make such a difference," Fairchild says.

Other helpful adjustments include extra lighting around the house and lighting with different level settings. Increasing the contrast in the home also helps. For example, if a living-room chair is dark-colored, put a light-colored throw or pillow on it to make it easier to see.

Services for the blind and people with low vision also teach people how to take advantage of technology — everything from how to access the free Library of Congress Talking Book Libraries in every state to using assistive technology for computers and smartphones and even a device that reads the labels on prescription medication bottles.

Safety, Health and Wellness Issues

People experiencing a progressive eye disease face safety and health risks. Falls and medication mistakes, for example, send many people with low vision to the hospital every year, Fairchild says. Another problem is loneliness and social isolation, which are known to negatively affect overall mental and physical health.

"It's not unusual for people to isolate, because getting out is hard," Fairchild says, adding that many people having trouble seeing become afraid they will fall or get lost. "And because of the isolation, depression is very common. We, as family members, have to watch for that and make sure that they still have a quality of life that's appropriate for their age and health."

"It's not unusual for people to isolate, because getting out is hard. And because of the isolation, depression is very common."

Stigma Associated with Visual Impairment

There's also a stigma associated with vision loss that discourages people from seeking help. Some people try to hide their visual impairment because they're embarrassed by it. And some don't want to inconvenience others.

Gittan Maier, 78, of Wappinger Falls, N.Y., felt this way at first about her vision loss due to macular degeneration, which has been progressing for 12 years. This age-related eye disease affects the central part of the retina, causing blurriness or dark spots in a person's central vision. Among other challenges, it makes recognizing people's faces very difficult.

"You know when it bothered me the most?" Maier asks. "My best friend has two grandchildren who do all the drama plays at the high school. And she always invited me and I never wanted to tell her that I really couldn't see them. I could hear them of course, but I couldn't see them."

Eventually, though, Maier realized that she just needed to speak up.

"And I finally said to her, 'Can we sit a little bit closer so I can see them a little bit more clearly?' Because it's not a thing to be ashamed of that you can't see, but I didn't want to tell anybody," she says.

Today, Maier says when people approach her and she doesn't know who they are, she just lets them know she can't see them.

Like Owens, Maier also went through a difficult time, struggling with her vision. Eventually, she had to give up driving. And two years ago, at 76, she stopped working as a bank teller at TD Bank in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

"And let me tell you something, if my eyes were good, I would still be working. I loved my job," she says.

Maier also hated giving up driving. "That was my independence that got taken away from me," she says. But she adds that she's lucky to have a husband who is willing to drive her anywhere she wants to go.

The ‘Attitude Adjustment’

Fairchild has seen many people dealing with vision loss go through what she calls "an attitude adjustment," at first not wanting to accept anything other than the good vision they once had.

The adjustment is "an acceptance that there's not a magic bullet. There's no one pair of glasses that's going to fix it, there's no surgery, there's no pill, there's no drops," Fairchild says. "And then, deciding that they're not willing to accept less of a life than they expected to live because of vision loss and going out and finding those tools and techniques that will let them continue to live life to the fullest, in an independent and productive as they want to be."

This was something Maier finally realized. "Well, I said to myself, 'There's nothing you can do about it, so I have to seek help,'" she says.

How Low-Vision Specialists Can Help

Maier found help from optometrist and low-vision specialist Dr. Bruce Rosenthal, chief of low-vision services at the Lighthouse Guild, a nonprofit eye care organization in New York City. Low-vision specialists are optometrists or ophthalmologists who, in addition to diagnoses and treatment of eye diseases, help people function better with their visual impairment.

Low-vision specialists work with patients to discover their specific needs related to daily life, work and pastimes, and equip them with high-quality magnifier or telescope lenses and other devices that help them accomplish those things.

"A lot of patients are told in eye exams that nothing further can be done, and, interestingly enough, something further can be done," Rosenthal says. "We're going to spend time with the patient … sometimes forty-five minutes to an hour in an evaluation. And I'm taking a medical history as well. I want to know what's going on. … I want to get an idea of how somebody is functioning."

"It's important to understand why the vision loss has happened and if it's progressive when working on solutions," says Dr. Stephanie Fleming, an optometrist and low-vision specialist at the Center for Vision Health in Dallas. She says too often, people struggling with low vision don't seek the help of a specialist, and Rosenthal agrees.

"More than one person has said to me, 'Why didn't my doctor refer me here?' "Well, a lot of doctors, it's not that they're being negligent, they're too busy. It's our health care system. A lot of doctors see an awful lot of patients, and they just don't have time. Number two, they really may not know who's in their area that does this kind of work," says Fleming.

To find low-vision specialists, Rosenthal recommends calling the state branches of the national eye care professional associations: the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Optometric Association.

Resources and Services for Low Vision and Blindness

- American Foundation for the Blind: The foundation helps people with low-vision problems, as well as those who are blind. The website is loaded with information about various eye conditions and resources.

- Visionaware.org: A website for people with visual impairment or blindness, including information about eye conditions, daily living, emotional support and a special section for older adults. A search-by-state function provides lists of vision-loss services.

- State services for the blind and visually impaired: Every state has services for people with vision loss and blindness. Search on your state’s website or call your main state office.

- Braille and Talking Book Libraries: Every state has this program, which is free (including the device and shipping costs for audio books) for people who are eligible. There is an application process and it requires certification by a doctor, registered nurse, therapist or other staff person of a health care organization, school or public or private welfare agency.