Cybercrime Is on a Roll and Older Consumers Are Paying the Freight

In this 'season of giving,' make sure you don’t get taken

When he was in his 90s, my father's phone rang on the end-table next to his favorite recliner. He heard a voice from the other end say, "Hey, it's your grandson!"

"Rob?" asked Dad.

"Yeah, how are you?" replied the voice. After some generic small talk, "Rob" began unwinding a tale of personal woe. He was in some kind of trouble and needed money.

Fortunately, Dad's nonagenarian "B.S. meter" was still acutely tuned and he recognized it as a scam and ended the call before any damage was done. In fact, these so-called "grandparent scams" have become a common device for thieves targeting older Americans, whom they know have a soft spot for their grandkids and other family members.

Why Scammers Target Older Adults

Even in the age of the internet and Caller I.D., the telephone is still a potent device for duping people out of their savings. Potential victims field calls from a range of grifters claiming to be from Social Security, an IT "help desk" offering to "save" them from some imagined computer virus (the most prevalent ruse of this type), or most audaciously, even their own family members. (Social Security, the IRS and other government agencies will not contact you by phone to ask for money or personal information.)

"Cyber criminals have realized that a lot of the older consumers have a nest egg."

Legendary 1930s larcenist Willie Sutton was once asked why he robbed banks. His famous response: "That's where the money is." Today, the internet is where the money is and elders are prime targets for bad actors, partly because the web robbers have adopted Sutton's philosophy.

"Cyber criminals have realized that a lot of the older consumers have a nest egg," explains Benjamin Yankson, assistant professor at the University at Albany's College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity. "And so the wealth accumulation that they have automatically makes them a prime target for financial crime or cybercrime."

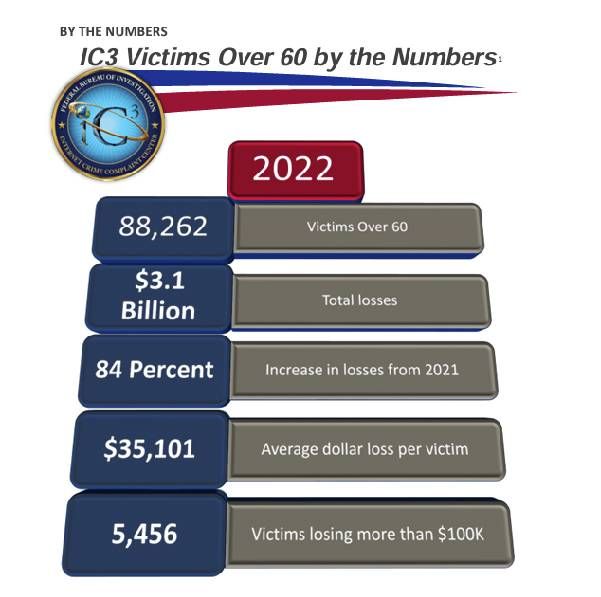

Older Adults Lost $3 Billion Last Year

The FBI reported that cybercrime victims over 60 years old lost more than $3 billion in 2022, an 84% rise from the previous year.

Yankson, 46, says that while wisdom (usually) comes with age, he also thinks older generations tend to be more trusting of strangers. "In the era they grew up in, trust was very significant," he says. "And so they seem to be a bit more trusting."

Yankson says older adults also tend to be less savvy about rapidly developing digital technology than younger consumers are, and they often are more socially isolated, which makes them more likely to engage "when a stranger calls" . . . or texts, or emails.

The "Nigerian Prince" ploy is so well trodden that it scarcely needs an introduction. (It's actually a variation of the "Spanish Prisoner" con from more than a century ago.) Nearly everyone has had email (or texts or an invitation via social media) from some purported high official, former official or royalty of a foreign country, who has an astronomical sum set aside for you if you just respond to their email and provide some personal information, along with a smaller-but-nontrivial sum to help free up the alleged riches that await you.

Partly because of the many variations on this theme and the sheer volume that go out, the scam is still raking in ill-gotten gains and Nigeria remains a hotbed of hustlers. The degree of gall in some of these is almost laughable. An email that went out last year claimed to be from "Merrick B. Garland, Attorney General," who was allegedly waiting to send you $1.5 million as a settlement for some mostly incoherent reason.

How's the Phishing?

The goal of many internet crooks today isn't even to get cash from you directly, but to harvest personal information that they can use to steal your identity. This is known as "phishing" and it takes many forms.

"No one is really immune to becoming a victim."

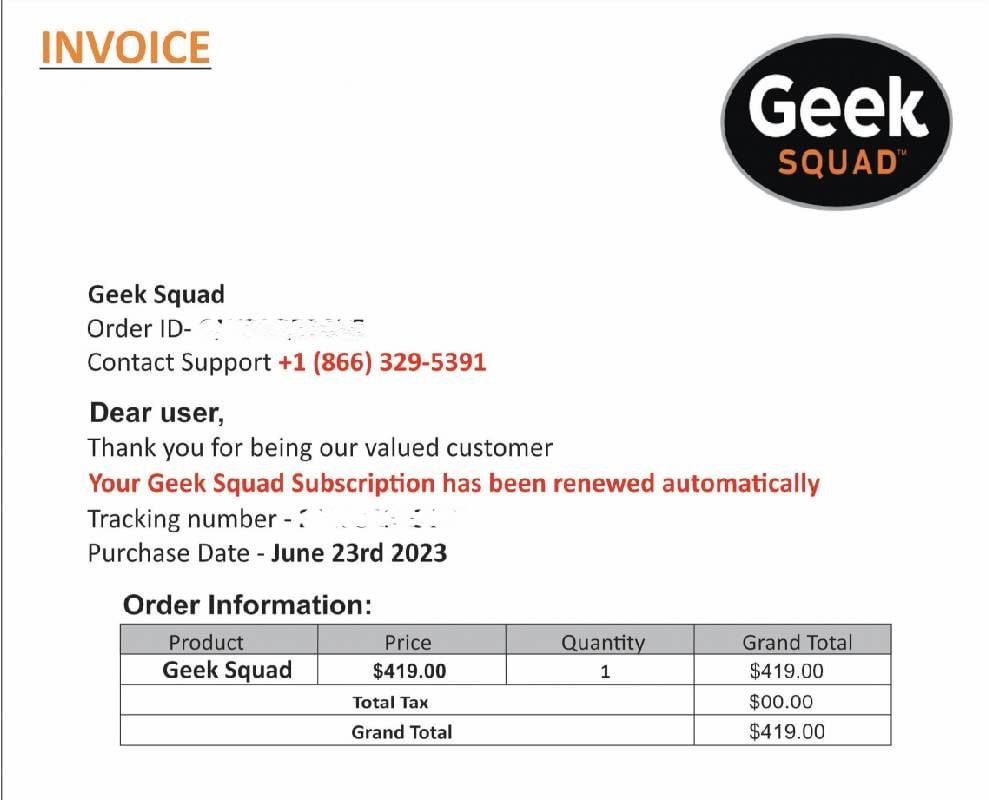

Attacks highly targeted to an individual are known as "spear phishing." It could be a friend request on Facebook, a text from some stranger, or an email claiming that something bad will befall you if you don't take immediate action: your Social Security or some other account will be suspended or saying you've been charged some exorbitant sum on your credit card to renew a service you don't have. These often take the forms of "invoices" from thieves posing as legitimate businesses, such as Geek Squad or Netflix.

"No one is really immune to becoming a victim," says Thomas Vallario, the Information Security and Compliance Analyst at New York Institute of Technology. "It doesn't matter how small or insignificant you think the information may be, it can be sold and exploited by hackers for their benefit."

One way to bust these bogus emails is to check the actual email address that sent it. It might be disguised with a subtle misspelling or a pseudonym that makes it look legitimate but click on your email client where it will show the actual source; chances are it'll be somebody's personal Gmail account or other address. If it didn't come from the actual internet domain of the purported business, dump it. An example would be this particularly uninspired attempt from "Vladimir:"

I NEED YOU AS A FOREIGN PARTNER FOR AN INHERITANCE CLAIM IN MY BANK. EMAIL ME IF INTERESTED TO PARTNER WITH ME

"Vladimir" might've been hoping that "shouting" in all caps would make up for his lack of inventiveness (and punctuation).

Until recently you could scan messages for poor grammar, typos and spelling errors. In the summer of 2023, an email arrived from a careless crook, announcing that "at your request," I was being upgraded to YouTube's premium service. The note included this text:

"As per your request, we are upgrading YouTube to YouTube Premium for the next year at a cost of $169.99. This amount will be deducted from your bank account within 24 business hourd"

The misspelling of "hours" and the lack of a period at the end of the sentence were tipoffs. Another giveaway with this come-on was the "time bomb." Most emails that threaten some action unless you reply right away are fraudulent. If you called the "support" number listed to inquire about the notice, you would have already taken the bait.

The Newest Threat: AI

But the field is rapidly tilting in favor of the bad actors. "The big thing now is email phishing and the use of AI (Artificial Intelligence software)," says Vallario. "Hackers like to use tools that are simple, easy, effective and cheap," he adds. "That's what they're going for. And that's exactly what AI provides. It's changing the landscape of phishing and not in a good way."

One result is far more sophisticated attempts to reach into your pockets. "Not a long time ago, you'd get these emails with spelling errors or incorrect grammar and you'd be able to spot it right away," notes Vallario. "Now, with AI, these attackers are writing perfectly written emails, and you can't tell the difference."

Vallario adds that crooks can harvest personal data from other security breaches on the web to make their phishing emails more personalized. He says that with the frequency of data breaches today, "we've all become a victim at some point," and may not know it, as companies are often not even required to disclose when they've been hacked.

Thwart the Grandparent Scam

AI has also migrated to telephone fraud. The "grandparent" con is already being updated with software that can mimic the voice of someone familiar. "That's become very frightening honestly," says Vallario. "And the technology is still relatively new," meaning it's bound to improve. The best defense against this type of call is to hang up and make a separate call to the person they claim to be, using the number you have in your contacts, to verify their identity.

The sheer universal connectivity of today's world makes everyone more vulnerable. Yankson directs a new lab devoted to social impacts of the "Internet of things," such as kitchen appliances in your home that are connected to the Web. And yes, if you have one in your home, even your fridge could sell you out. An appliance could be a gateway to data stored on your personal laptop, for example. Yankson's Hack-IoT (Internet of Things) Lab in Albany has found vulnerabilities in a "domestic robot" that's already on the market, designed to assist with routine tasks.

Call the Cyber-Cops

"This is not theoretical," says Yankson. "This is what is actually happening out there."

Both experts interviewed by Next Avenue agree that it's important to swallow hard and report it. Every scam that goes unreported is a boost to the bad actors. They also agree that public education is the best defense in a very old conflict.

"This [game of] 'cat-and-mouse' has been going on for hundreds of years, and it's going to go on long after we're all gone," says Vallario. "The technology part of it — the laptops and computers — that's just the new medium. It's always going to be a constant battle between good and bad."

What to Do if You Are Victimized

To report internet fraud, you can contact the FBI's Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) at (202) 324-3000, the bureau itself or its tips hotline. Tom Vallario has some tips for the holiday season security in his recent blog post. There are more helpful resources at IC3, AARP and the Federal Trade Commission.

Read More