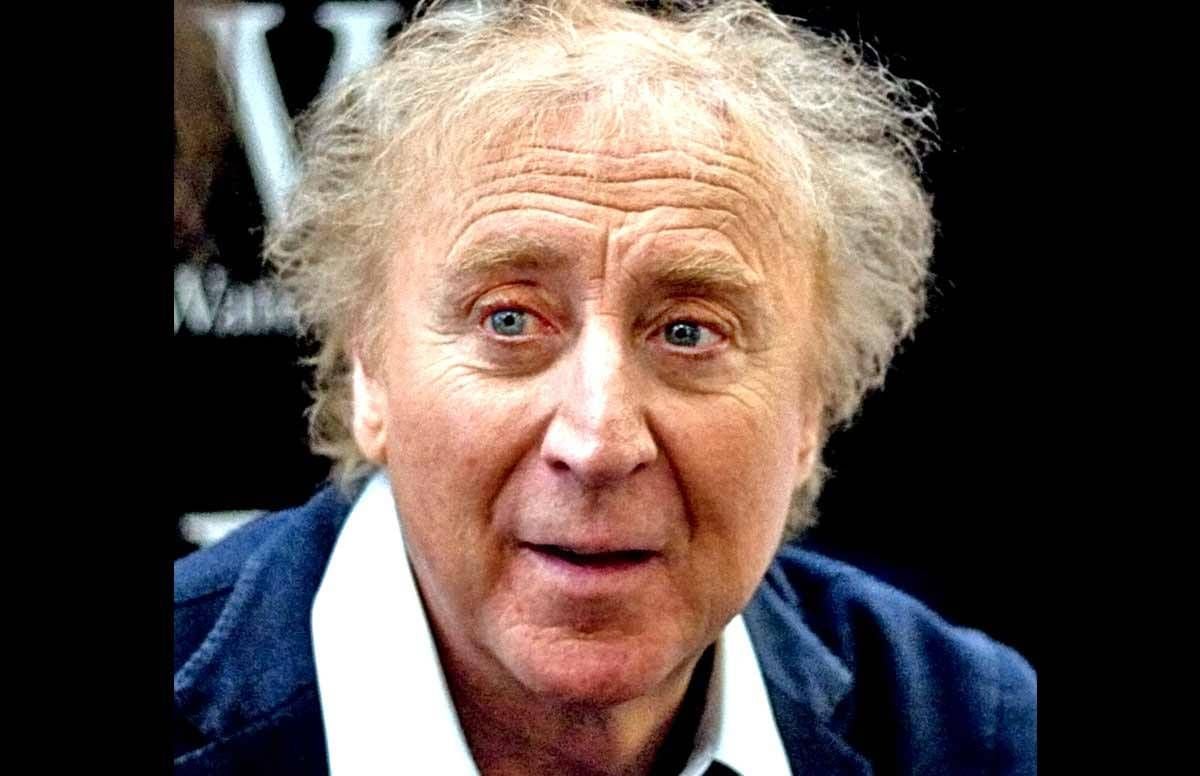

Gene Wilder and His Alzheimer’s Secret

He didn’t want to sadden children, but many feel shame with the disease

In 2016, news of the death of beloved comic actor Gene Wilder at his Stamford, Conn., home came with a surprise revelation: Wilder suffered from complications of Alzheimer's disease. He died Aug. 29, 2016 at the age of 83.

Wilder had kept his condition a secret from all but family, but it wasn't out of vanity, according to a written statement by his nephew, Jordan Walker-Pearlman, the Associated Press wrote. Rather, Wilder did not want young fans of Willie Wonka, the character he played in the 1971 movie, Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, to be let down or worried.

The children who recognized him "would not have to be then exposed to an adult referencing illness or trouble… He simply couldn't bear the idea of one less smile in the world," Walker-Pearlman said.

In addition to Willie Wonka, Wilder "brought a unique blend of manic energy and world-weary melancholy," as the Los Angeles Times put it, to films from Young Frankenstein to Blazing Saddles to The Producers and more.

A Difficult Topic

Wilder and actor-comedian Gilda Radner married in 1984; after she died of ovarian cancer in 1989, he worked to raise awareness of the disease and donated money for a research center in her name.

In generations past, cancer itself was a taboo subject, often referred to as "the C-word." Today, when it comes to illness, Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia are surely among the most challenging to talk about.

Actor Seth Rogen and his wife Lauren Miller Rogen launched their Alzheimer's support organization Hilarity for Charity after her mother, Adele, was diagnosed at age 55 with early-onset Alzheimer's. By 60, Adele had forgotten how to speak, dress herself, feed herself or go to the bathroom alone. Since then, the Rogens have advocated for more research funding and better support for families living with the disease.

"Americans whisper the word 'Alzheimer's' because their government whispers the word 'Alzheimer's,' and although a whisper is better than the silence that the Alzheimer's community has been facing for decades, it's still not enough," Rogen told a Senate subcommittee during a Feb. 26, 2014 hearing. "It needs to be yelled and screamed to the point that it finally gets the attention and the funding that it deserves and needs."

Hilarity for Charity tweeted after his death: "To most, it was a surprise that Gene Wilder had Alzheimer's. We strive to erase the stigma so that no one has to keep this disease a secret."

The Dangers of Stigma

The United States government funds Alzheimer's research at a lower rate than it does other diseases — and stigma may be partly to blame, according to the Alzheimer's Association. People do not want to talk about it, be associated with it or be labeled by it. But with attention comes dollars.

"There is a growing body of work that suggests that stigma promotes social exclusion and reluctance to seek help," said the World Alzheimer Report 2012: Overcoming the Stigma of Dementia, by Alzheimer's Disease International, a worldwide federation of Alzheimer's groups.

"In all stages, the stigma associated with dementia also leads to a focus on the ways in which the person is impaired, rather than on his or her remaining strengths and ability to enjoy many activities and interactions with other people," the report continued.

Because stigma can prevent individuals from seeking treatment for symptoms, the Alzheimer's Association says, it can delay a diagnosis and thus treatment. The stigma can keep people from living their best possible lives and making necessary plans for the future. And it can prevent them from participating in clinical trials that sorely need volunteers.

Shying Away?

A sad story: Visiting Angels home care franchise owner Angil Tarach-Ritchey wrote of holding an event in Ann Arbor, Mich., for the 2010 National Memory Screening Day, organized by the Alzheimer's Foundation of America. "The day ended with us all very disappointed," she wrote, "because no one showed up. Not one person came to receive a memory screening, view the presentation or to get educational materials, ask questions or receive support."

Maybe people don't even want to be seen going into a place where there was to be a "memory screening," Tarach-Ritchey concluded. "There would never be that kind of fear in a health screening that included blood pressure checks, blood sugar checks, or other assessments of physical health issues. The fear and stigma of mental health diseases is so sadly true … Somehow, some way, we need to change our thoughts about brain diseases and the people affected."