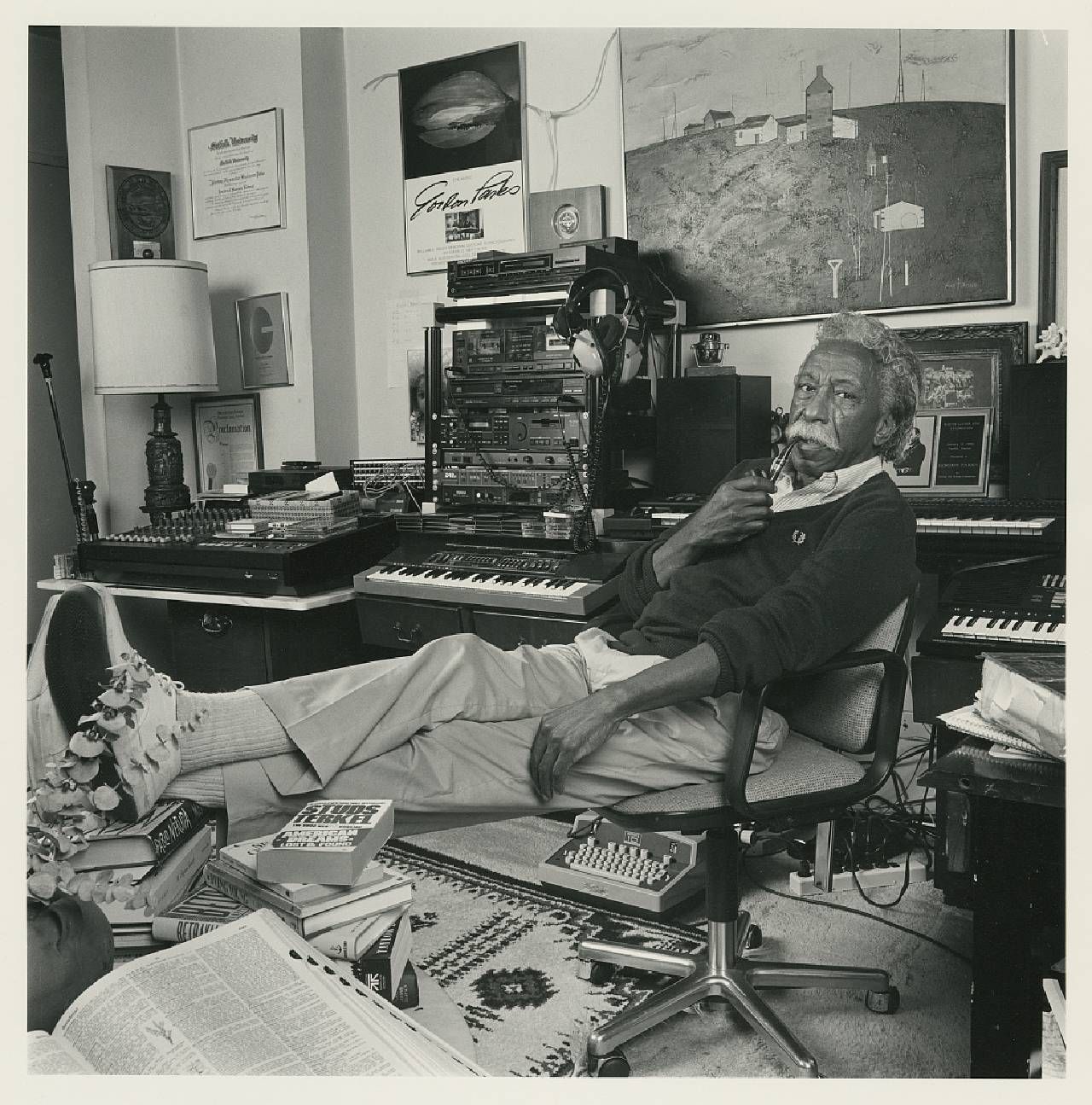

Photographer Gordon Parks: His Unshakeable Peace Endures

Looking back at the transcript of an interview that Gordon Parks gave more than 30 years ago resonates even more meaningfully today

I've been a journalist for twenty years, but long before that, I was building the foundation for this career. Not just by writing, but with all my "money jobs" to sustain myself while I wrote plays and fiction. In the last few years, I've found those experiences birthing journalism and insights.

I know now that photographer and Renaissance man Gordon Parks (1912–2006) changed my life. I never met him, but in 1996, in the midst of a career freefall, I got a job transcribing interviews for an agency. I was one of a team of transcriptionists that was assigned to work on photographer John Loengard's (1934–2020) interviews of the original Life magazine photographers.

Loengard was determined to memorialize them and their experiences while they were still alive. He videotaped them in 1993 and three years later we transcriptionists were given tapes of the audio.

Transcribing, for me, is a full-body experience: you receive the voice through headphones and it travels down to your arms and out through your hands, while your feet work a pedal controlling pauses and starts of the tape. So, in essence, somebody's voice and the energy it carries do a loop-de-loop through your body.

The Relaxed Tone of Voice

Today, in 2024, as I read the proofing transcript I saved of the Gordon Parks interview, his tranquil, unhurried voice rises through the words: fragmented sentences that Loengard would later edit or eliminate for his book "Life Photographers: What They Saw." And almost immediately, on feeling Parks's coherence — his relaxed, self-accepting flow — I react like a present-day tuning fork, immersed in sympathetic resonance. My breathing deepens, heartbeat slows, synchronizing with Parks.

I bathe in his effortless generosity as he recounts inviting members of a Harlem gang to his home in the country, to play with his kids and ride horses.

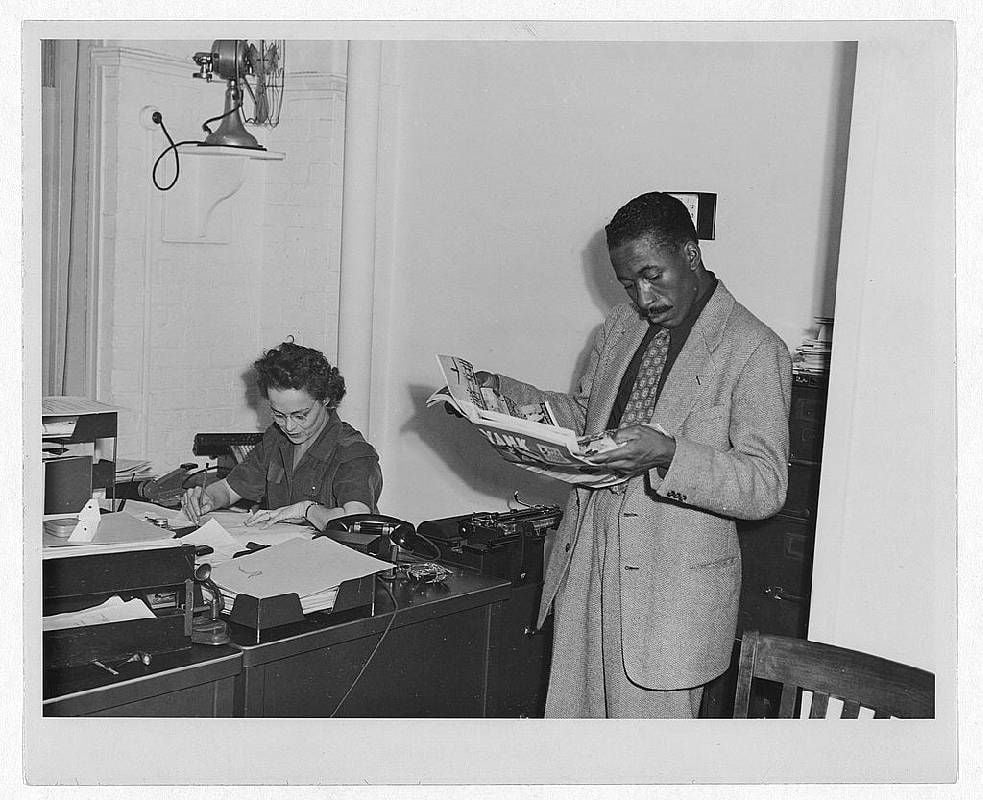

I bathe in his effortless generosity as he recounts inviting members of a Harlem gang to his home in the country, to play with his kids and ride horses. He was covering the gang for a major story, and, since he often quotes dialogue, he brings me to the streets of Harlem in 1948 — makes me see and feel the danger of gang leader Red Jackson — but, as Parks was, I'm relaxed.

When he'd received the assignment, he says, "Frankly, I didn't believe I could do the story. But I put myself out there and why not try?" And with the same curiosity he has for all people, he befriended a cop who introduced him to Red. And later in the interview, almost as an afterthought, he mentions that the reason he fell into a friendship with Red and his boys was that he'd hoped to expose them to a way of living and a place that they didn't know existed.

This calm, steady vision directed Parks's relationships with everyone, and in fact it was the way he lived. "Why not try?" seemed to be his mantra. He got the coveted job at Life because one day he decided to walk into picture editor Wilson Hicks's office to see about work — no appointment; his attitude was "what do I have to lose?"

Thoughts on Henry Luce

He met the publisher of Life, the elusive Henry Luce, with a similar gaze. He rejected the common rumor that the man wanted nothing to do with anyone. " ... [W]hen I used to see him on the elevator, I thought he was very aloof. He didn't speak to anyone. Sometimes they just let him go up on the elevator alone, and I didn't like that very much, but this morning after I had visited his home [when Parks was doing a fashion shoot in Paris], he was standing in the corner and I said, 'Well, good morning, Mr. Luce.' And he says, 'Oh, good morning, Mr. Parks, how are you?' and he talked all the way up the elevator shaft. And he couldn't stop talking. And I realized the man was just a little shy. He was not aloof whatsoever."

No matter who he encountered, Parks remained neutral and curious. In the 1960s when he was sent to cover the Black Panthers, this outlook became more conscious. "I knew Life magazine didn't know whether or not they could trust me out there ... whether I would do it fairly, whether or not I would lean with them one way or the other."

And Malcolm X was similarly distrustful of Parks because he was working for a white company. But when Parks refused Panther money to make a documentary about the group — without a pause, turning down half a million dollars because he didn't want to be beholden and therefore pressured to share Malcolm's point of view — he was allowed entre.

"But you weren't intimidated?" asks Loengard.

"No, I was not intimidated," answers Parks simply.

About his early life, Parks says "I was surviving more than anything else." He'd dropped out of high school and was frightened. His parents and 14 brothers and sisters all wanted him "to be somebody" so he was determined to "be somebody." Hence, while he was trying to just "hang on," he played piano, basketball and herded cattle. "The photography was an accident. Everything was an accident," he shrugs.

This man may have been frightened about his early survival, but in a profound way, he was fearless. And I posit that it was because he was so grounded in the "nothing to lose" belief that he was available for amazing accidents (which he and many other Life photographers call "luck") and the extraordinary life of creation he ended up living.

Because he knew nothing, Parks was not afraid to ask for help. While at Life, he knew nothing about lenses and got help from Life laboratory technicians who gave out equipment.

Seemingly effortlessly he shifted between glamorous fashion and movie star shoots to poverty, cops and robbers, and Al Capone. "I had the capacity to readjust so quickly," he explains. "I always say it's because I was brought up in Kansas where you had to readjust if you were Black, very quickly, you know."

So shifting between diametrically opposed job environments was easy: "I just said, well, I'm in a different kind of story. I didn't anguish over it one way or another." Yet his empathy with his subjects is palpable. So he had a miraculous combination of detachment from a story, but deep feeling and connection to the people playing out the stories.

Pen to Paper

Transcribing Gordon Parks was help I didn't know I needed in 1996, but I'm only just now realizing it has accrued interest over time. Originally, it was such an emotional experience that I had to express it, so I wrote this letter to Loengard and his video producer, Kathy Sulkes:

April 15, 1996

Dear Ms. Sulkes and Mr. Loengard:

I have been transcribing tapes of your Life photographer interviews. When I found myself weeping and making noises, and periodically having to lie down on my living room floor to digest what I was hearing, I knew something profound was going on.

After my first batch of tapes [which included Gordon Parks], I wanted to talk, but when I delivered my work to Wordflow, I felt a little funny about expressing such intense feelings. No need. They had heard it all before. Everything I said — from the research I was doing to get correct spellings because I felt so honored to be allowed to work on this that I wanted to get it right, to my emotional response — everything I said, I was told another transcriptionist had said the same thing. Apparently this material had transcriptionists all over New York City buried in reference books and weeping at their computers.

And I was suddenly overcome with the feeling that I was part of something huge — an immense wave that 60 years ago drew people in from all over the planet and sent them out to witness Life and transmit their impressions to others. And now, all these years later, that same wave had pulled these witnesses back in again to testify. And it is no accident that this began with a man named Luce (light).

Listening to these oral histories of people in their 70s and 80s has been a deeply spiritual experience. Cornell Capa seemed to articulate what has moved me so — the idea that the job was/is to share witness in order to make things better.

You have an incredibly powerful body of work here. I hope you will send it out to the world and let it sing.

Had I known this was what history was when I was in school, I would have listened.

Sincerely,

Betsy Robinson

And here is his handwritten reply on a Georgia O'Keeffe postcard, dated 4/29/96:

Dear Betsy Robinson,

Thanks for your letter about the LIFE Photographers tapes—I've passed it on to Kathy Sulks [sic] and others, at LIFE. So far there's no movement towards getting it on the air but a comment — reaction —like yours is a help.

Thanks,

John Loengard

Loengard died in 2020, but he did manage to publish "Life Photographers: What They Saw" in 1998. It includes edited interviews of Gordon Parks and 43 other Life photographers who were on staff between 1936 and 1972. Also included is their photojournalism and a gallery of photojournalist portraits along with a comprehensive selected reading list and an index.

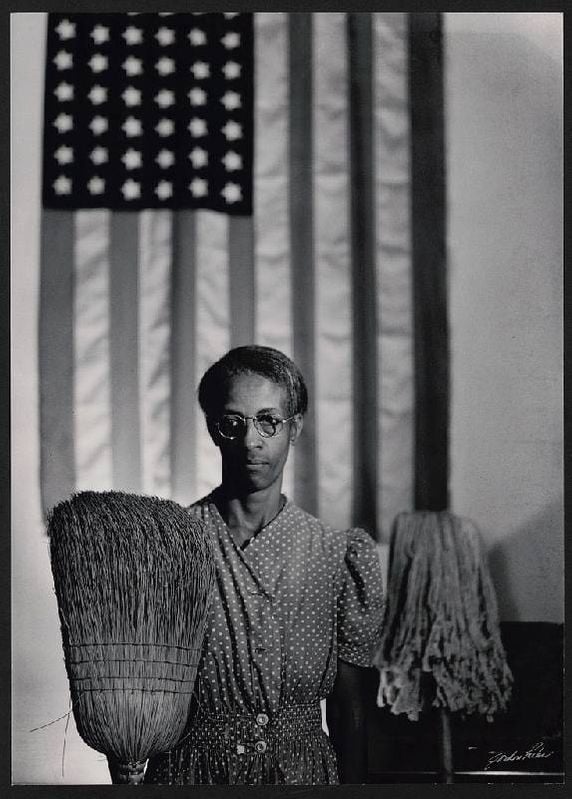

Gordon Parks and so many others whose voices still resonate inside me understood their jobs: to witness, spread truth, to make the world a better place.

Over the years, I've told many people who work in radio about the existence of these tapes and video. So far, nobody has succeeded in tracking anything down. And I imagine the video has long since decomposed and who knows what's become of the audio cassettes.

In this essay, I have quoted brief passages from my proofing transcript in the spirit of praising this work — as a reviewer of both the transcript and the published book, which the copyright notice says is allowed.

Gordon Parks and so many others whose voices still resonate inside me understood their jobs: to witness, spread truth, to make the world a better place. This many years later, merely reading Parks's words touches personal places, makes me feel the fearlessness of "Why not?" Why not try out my ideas? — I'm starting my own publishing company, Kano Press. Why not ask famous people for book blurbs?

Why not write this article conveying the energy of fearless generosity of an extraordinary human long after his death? Why not be peaceful and fearless — no matter what is going on around us? What else have we got to do? We'll either succeed or fail, die or live. Why not share what I witnessed almost three decades ago? Isn't that the job: to witness and share and hope it'll make things better?

Editor’s note: For more information, visit the Gordon Parks Foundation. They are currently sponsoring an exhibit of Mr. Parks’s work, “American Gothic: Gordon Parks and Ella Watson,” at Mia (Minneapolis Institute of Art) in Minneapolis through June 23, 2024.