Touch the Screen and A Memory Appears

The House of Memories app sparks connection for those living with dementia

Stories shared around the dinner table or nostalgic anecdotes about “when I was a kid” often become rarer when a loved one living with dementia is eventually left with limited access to his or her precious memories.

Family members and caregivers, struggling to maintain connection, often turn to photo albums to spark recognition or create talking topics. While images of family and friends, past celebrations, vacations or former homes and neighborhoods can provide touchpoints, historical photographs of events, objects, locations, food, sports memories and more — all common to a generation — also have the power to launch meaningful conversations.

In September 2018, the Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) unveiled a new digital app called “My House of Memories,” which can be downloaded free of charge to a tablet or smartphone. This first-of-its-kind app features a carefully curated selection of more than 100 pages from the MNHS museum collection, each filled with an array of images intended to be enjoyed by people with dementia, their caregivers and family members.

The “House of Memories” museum-based dementia program was originally launched in the U.K. in 2012 by the National Museums Liverpool, and MNHS is the first museum to offer a U.S. version.

“We are proud to be working in partnership with the Minnesota Historical Society to launch House of Memories in the U.S., to help Americans to live well with dementia,” said Carol Rogers, executive director for education and visitors at National Museums Liverpool, in a press release last year. “Person-centered care is at the heart of our training and acknowledges that an individual’s personal history and memory are of huge importance. Museums can be fantastic resources at helping unlock memories, improve communication and understanding, and enrich the lives of those living with dementia.”

Universal Objects Resonate

Maren Levad, museum access specialist for MNHS who has managed its House of Memories project from the onset, said the selection of images for the app was done in a very purposeful way, including a two-year period of research around the state of Minnesota to curate universal objects that would resonate with the dementia awareness program’s intended population.

“The image choice was very important; there have to be multiple ways for people to engage with what they are seeing on their screen,” said Levad. She and other curators visited community centers, assisted living facilities and other locations, interviewing people ages 45 to 100, about objects that provoked positive and nostalgic feelings.

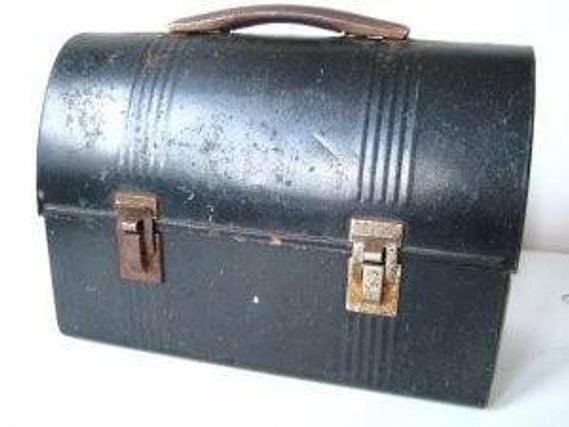

For example, when people were shown photos of lunchboxes, the rounded black version was the overwhelming choice to serve as the true representation of an old-time lunchbox, especially by residents of northern Minnesota, said Levad.

“We also learned that veterans were very particular about imagery. They wanted all four branches of the service depicted, as well as different parts of the uniform,” said Levad, adding that in speaking with veterans, she also learned that “a real ditty bag has to tie on the top.”

According to Levad, researching and curating cultural elements for the app was a crucial part of the project. Members of the team visited with African American community residents to talk about images and objects that resonated in a particular way with their population. One photo, circa the 1950s, shows a lively dance party in St. Paul.

According to research provided by the MNHS, African Americans nationwide are more than twice as likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease than non-Hispanic whites. Currently, the Alzheimer’s Association reports that 5.7 million Americans have Alzheimer’s.

During the app's testing and evaluation phase, before its official launch, Levad and her team received encouraging feedback from early participants: 80 percent reported that using the My House of Memories app “enhanced my ability to connect or have conversations with the person I care for” and 70 percent reported that using the app “increases the likelihood that I will have conversations about personal or family history.”

How the My House of Memories App Works

The My House of Memories app, which has a simple look, features tabs highlighting information on dementia, app categories and clear instructions.

“Our software developers did research alongside persons who have dementia; there aren’t a lot of bells and whistles, you touch the screen, but don’t swipe on it, because that isn’t intuitive, and there are some sounds and music, but those can be turned off,” Levad said.

Categories include Sports & Leisure, On the Town, Days to Celebrate and Work & Play; in this last section alone, there are 16 depicted objects, 45 images and eight sounds.

Overall, images touch on many aspects of life in ways that can be sentimental, meaningful or humorous. There’s a photo of three babies in high chairs eating turkey legs (which Levad says has proven to be surprisingly popular), a picture of Elvis Presley, another one of fans at a Beatles concert and a picture of a three-legged milking stool (a very specific image that came out of the Minnesota focus groups).

As caregivers and family members engage the person with Alzheimer’s in the use of the app, Levad said the preferred strategy is to ask open-ended questions, although never starting with “Do you remember?”

For instance, if a photo of a 1950s kitchen is selected, suggested questions might include “What would you want to eat in this kitchen?” or “Do you have a favorite home-cooked meal?”

Even if the person with dementia no longer speaks, Levad said, it’s still important for him or her to be able to see beautiful photos; an image of a quilt might simply provoke a smile and a nod.

“We meet people where they are. Looking at these images together offer small moments of person-centered attention,” she added, also making it clear that the My House of Memories app is intended to be used with two people, and "not to serve as a babysitter.”

In addition to the museum images, the app can be personalized for the user in a My Memories section where that person's own photos can be added.

“When people move into an assisted living facility, sometimes it’s not only leaving a home that’s difficult, but leaving a yard or garden. Uploading photos of special places like that lets someone bring those memories along,” said Levad.

A Springboard for Conversation

Along with the introduction of the My House of Memories app, MNHS has offered training workshops for professional caregivers and family members across Minnesota. In addition to learning how to best use the app, the workshops focus on other skills which can be used when working with people living with dementia.

Maureen Aksamit, the cognitive health and wellness director for the Charter House-Mayo Clinic Retirement Living Community in Rochester, Minn., and her staff, participated in training led by team members who traveled to Rochester from the National Museums Liverpool.

“The app can be a springboard for conversation about something other than the weather,” said Aksamit. “It’s an opportunity to enjoy each other’s company.”

My House of Memories can also have benefits for other older adults. Aksamit has shared the app with some of the assisted living residents who only have mild impairments, and their response has been positive.

“Not only does it provide an opportunity for them to become more familiar with technology now, it’s also a way for them to create a visual memoir that they can always return to,” she said.