Third Hand: I'm A Backup Caregiver and I'm 200 Miles Away

Participating in my dad's care from a distance can be challenging, so here are some observations from my experiences

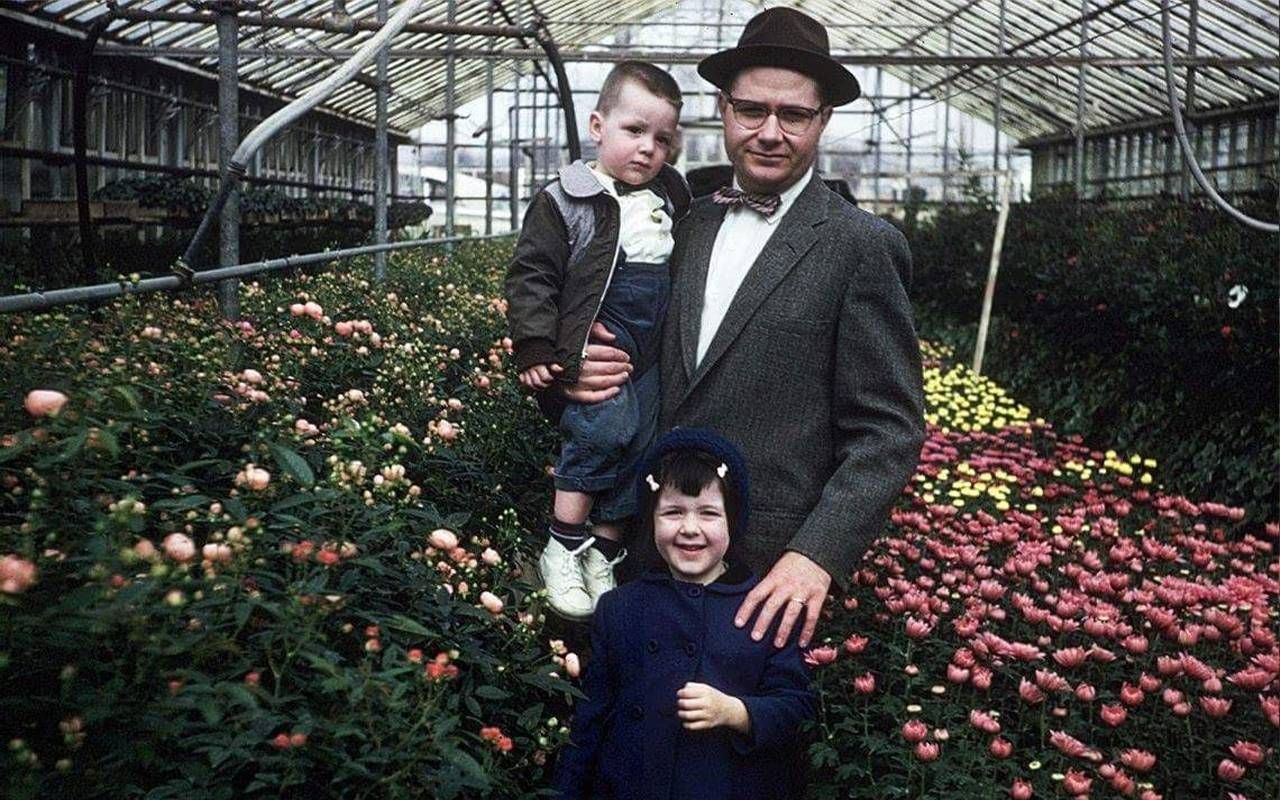

In the last year, my father — who has lived a long and robust life — has declined and is physically and mentally frail. Our family is saddened by his decline. Dad's mental state has often been sharper than those around him, so it is devastating when it is not.

I bragged to Dad recently that because of the books I've read, he could quiz me on any World War II battle date. "When was the Battle of the Bulge?" he asked about one of the most famous. I missed it by a year. Lesson learned: don't mess with an expert who's been reading World War II books 25 years longer than you have.

With me hours away, Andy, my only sibling, is Dad's primary caregiver.

In the Midwest, we characterize travel by how long the drive takes — the trip to Dad's is about four-and-a-half hours. We lose an hour going from Central to Eastern time. To arrive before noon, we leave around six a.m. if we include refueling and bathroom stops. With me hours away, Andy, my only sibling, is Dad's primary caregiver.

Andy helps Dad almost daily. Dad has lost much — mobility, eyesight, and overall strength and health. Andy takes Dad to doctor's appointments, takes him on short day trips, and brings him chocolate and other sweet goodies. Andy is the primary family contact for the facility. He lives about two miles away from Dad. I am the backup person.

My brother relays information well, but I sometimes need help. I worked in health care. I am interested in specific values from tests. My brother is more of a bottom-line person. We have worked this out; now that Dad is in assisted living, I have access to his medical portals to track his blood pressure and learn of changes in medication or doses.

Going to the dining room is like eating at a restaurant meal. It was important to Dad that Mom looked nice.

Dad uses incontinence products, which he bought in the basement store at the facility. He may have been too embarrassed to ask my brother for help. But the pads were poor quality, and Dad threw some clothes away, which tipped the nurses off to a more significant problem. So I thought, "This is an easy one. I can find out what he needs and have it sent monthly."

In what may have been a foolish idea, I asked my colorblind brother what I should get. His answer was, "Get the blue ones." Did he mean blue packaging or actual blue garments? Or did he mean green? Or magenta, the Pantone color of the year? No one will ever know.

I called the nurse's station for a recommendation. Dad gets excellent care, and I assumed they would know a particular brand for him. I expected a specific answer, Product X, Size X, and Thickness X. Instead, the nurse called me back and said, "I checked with the floor staff, and they think that Depends is the best."

Got it. Blue. Depends.

I'll be all over that.

If I don't laugh about this, I will cry.

When my mom was alive, Dad took meticulous care of her. She had vascular dementia. Dad helped her shower, placed her dental bridge each morning, put her earrings and jewelry on her, and dressed her. He insisted I take her shopping for new and fashionable outfits. Going to the dining room is like eating at a restaurant meal. It was important to Dad that Mom looked nice.

Knowing how Dad felt about Mom's appearance, it is hard to understand that Dad doesn't hold the same stock on his own. He is stubborn about his clothes and would only buy pants from a Yoder's in Shipshewana, Indiana, 150 miles away. We tried ordering from there, and it didn't work.

He was never happy with what he got. Meanwhile, with aging, he was losing weight, His pants often sag, and he holds them up with suspenders. My brother solved this problem so brilliantly. Andy bought Dad several pairs of pants, shirts and pajamas.

As family members, we share the same motivation: the best care and life possible for the loved one in decline.

While Dad and his girlfriend ate dinner two floors down in the main dining room, Andy put the clothes away in Dad's closet, and Dad would wear the items. Did he know they were new? We're not sure.

My mother didn't work outside the home and spent about 15 years as the primary caregiver for her parents. Her only sister lived on the East Coast and visited once or twice a year. My aunt was lovely and charitable, but Mom sometimes felt her visits were an inspection tour. Like me, my aunt wanted to help, and it was challenging to weigh in from a distance.

I've understood that hard place on either side, as the caregiver who lives nearby and the backup who lives far away. As family members, we share the same motivation: the best care and life possible for the loved one in decline.

What I'm Learning

So I've worked to be helpful and not critical, which is tough. Here are some thoughts from my experiences.

- Pay close attention to formal communication from the facility. Read their newsletter, the weekly COVID report, and the website. Engage in personal conversations with the staff. Keep a notebook to help jog your memory.

- Take advantage of every electronic portal available. Dad lived in the independent section of this facility for 17 years; he moved to assisted living in March, so now I can see his vitals or medication changes on the portal. I also can talk to any of his doctors. My health care background can bring a new perspective for my brother.

- Seek ways to help from a distance. For example, I check the newspapers for deaths in our hometown and send a card or flowers as necessary from our family. When he could still read, Dad often mentioned books he wanted to read. I would order them immediately, and he didn't have to wait months for the library to get the latest analysis of Lincoln or the two World Wars. Dad needed a few things for his move to assisted living, and I had them delivered: a shower chair, bathmat, and sheets for a smaller bed. My brother moved heaven and earth for the move, cleaning the old apartment and storage unit, selling some furniture, and removing extra items. My small errands reduce trips for my brother.

- Keep your mouth shut and tamp down the suggestions when visiting. This is so difficult for me as a Type A person. My brother even calls me his "Alpha" and laughs about it. But I am here to help; I am not leading an inspection tour with a need to weigh in on everything. Again, this is hard.

- Accept that some things don't work. I thought a whiteboard in the new apartment would be great to leave Dad notes on because he needs to remember. For example, "Amy is coming on Friday." "Tuesday is your laundry day. Almost immediately, the special whiteboard pen disappeared. I bought ten more. My nephew found the original pen on Dad's desk with ballpoint pens. Dad didn't understand that you needed a special pen for a whiteboard. We should have anticipated that. My brother says the board is gone, so it must have confused Dad more than helped. We tried. We live and learn.

- Sometimes, I have to throw up my hands in defeat. Dad doesn't drink enough water. I bought him a thermal water cup with a picture of his only great-grandson, whom Dad calls the "wee one" because he can't remember his name. I thought Dad would carry it everywhere. Nope. He doesn't want to drink more water. That whole "lead a horse to water" thing, well, you can't lead a nonagenarian to water from 200 miles away. My husband often threatens to buy me a shirt that says, "I'm 200 miles away." I have had to learn to let some things go.

- Love him any way you can. My brother and I are fortunate to have our father for 63 and 65 years. I call Dad daily, and it's usually a brief talk, though I tell him about books I'm reading. He eats up American history. I just finished "Booth" and told him about all the quirks of the family of the man who killed Lincoln.

At 93, he still engages in the world with a failing mind and body. Since college, Dad has played euchre, a card game popular in Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio. Dad always has a deck of cards in his Rollator seat.

Sometimes my brother will take Dad to play at his church or attend the Friday night euchre group at the facility. Dad and Andy, both agricultural majors, were members of the same fraternity at the same college, where euchre was popular. So when Dad and Andy are playing together, if they win a round, they yell, "Milk 'em, milk 'em, milk 'em," and then join hands in a motion like they are milking cows.

Dad can't remember what time church starts but knows all the moves he played in 1949 in the card game. What a gift when we can still see his flashes of brilliance and humor and still get a bear hug.