Lace Up Your Boots and Get Ready for a Long-Distance Walk

Your socks may get wet, but there's plenty to enjoy if you prepare for the challenge

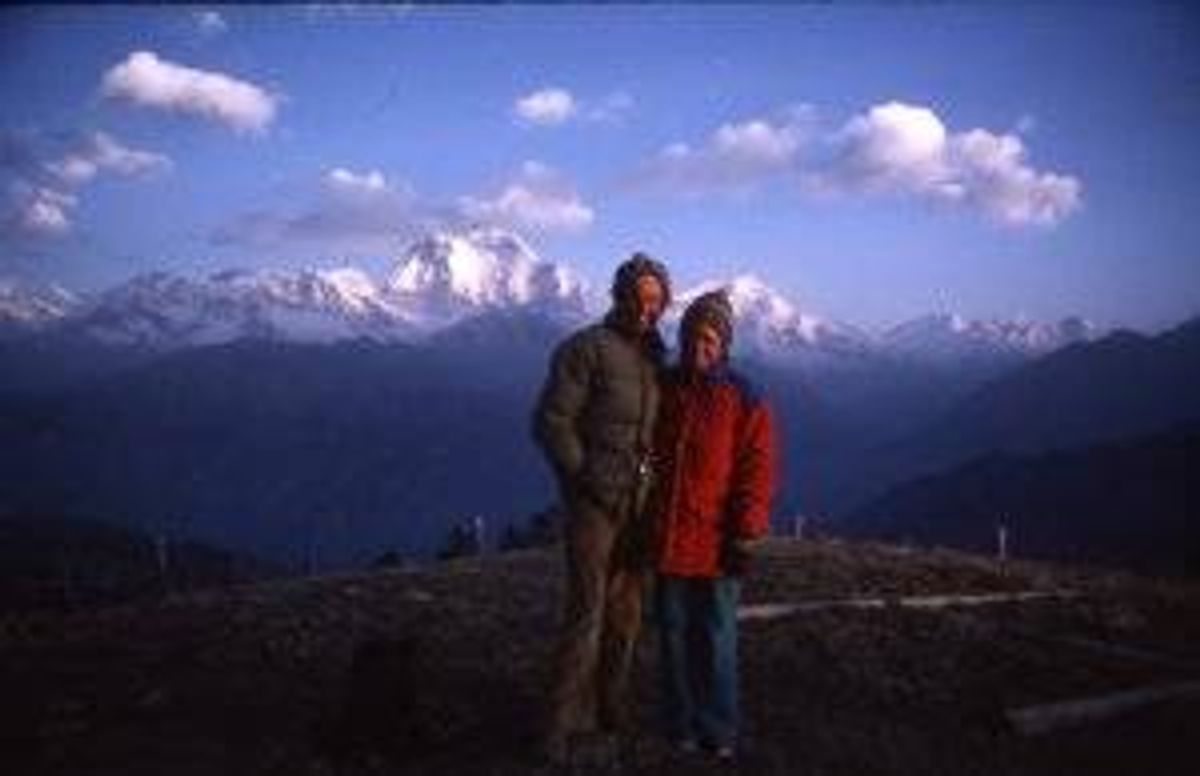

Every 10 years, my husband and I undertake a long-distance walk somewhere in the world. The year I turned 30, Barry and I spent three weeks walking the Muktinath Trail in the Himalayas. When I was 40, we walked the four-day Inca Trail, ending at Macchu Picchu. At 50, we hiked the 500-mile ancient pilgrimage route across northern Spain, the Camino de Santiago, and at 60, the “Coast-to-Coast,” 200 miles across the width of northern England, from the Irish Sea to the North Sea.

At 67, I may not be able to wait three years! I already feel the itch, and, as my mother-in-law used to say, "You're not getting any younger." So many walks, so little time!

Four Things I’ve Learned From Long-Distance Walks

I've learned four things from my long-distance walks. They may be helpful if you follow in my footsteps.

1. Long distance walking abroad is not the same as backpacking in the U.S. It’s often easier. On overseas walks, we usually sleep in beds, not on the hard ground. We stay in guesthouses (Nepal), mountain huts known as refugios (Camino) or B&Bs (Coast-to-Coast). We rarely need to carry food or cooking gear, because our hosts either serve us home-cooked meals or we eat in budget restaurants.

The walking environment isn’t the same as in America, either. Before our first long-distance walk, I had read about trekking in the Himalayas and it had taken on a mythic glamour. I could barely wait. We spent three weeks in the Nepali wilderness — except it wasn’t “wilderness.” The Himalayan trails are busy places, filled with yaks, shepherds, climbers, trekkers and porters carrying firewood and supplies to cater to hungry tourists. When Barry and I backpack in the U.S., we don’t run into shepherds! No villages, cafes, or shops populate the trails.

2. Physical preparation matters. I had been backpacking every summer for eight years before we went on our first long-distance walk. That prepared me for thru-hiking, though there were times I wished I had prepared more. While Barry is Welsh and we’d previously hiked many of Britain’s National Parks, the Coast-to-Coast reminded us how muddy and wet British trails could be.

Our fellow hikers were, as the British say, well-kitted with waterproof boots and gaiters. Not us. Virtually every night in a hostel I’d park my soaked boots in an “airing cupboard.” By morning they’d be dry, only to turn wet again by night, because even if it didn’t rain that day, the soil was still puddled and muddy.

On the Camino, we brought too much and ended up shipping a box to the town of Santiago de Compostela, our destination. When we arrived at the post office to pick up our stuff, we discovered we were not alone: a whole area of the room was dedicated to shipments from peregrinos (pilgrims).

I’m more aware of physical vulnerability now. I pack light to put less stress on my joints. It’s easier to do that today, thanks to lightweight equipment and digital maps. And no more heavy leather hiking boots.

We never booked overnight stays in advance until we hiked the Coast-to-Coast in 2011. During breakfast at our B&B in Grasmere, a village in the Lake District, Barry pulled out his iPad to reserve a room for the evening.

Our owner, bringing a full English breakfast plate to the table, frowned.

“Manners maketh the man,” she said.

“Shakespeare?” Barry asked, covering his embarrassment.

“William of Wykeham,” she corrected tartly.

Nowadays, everyone would be on their phone.

3. Mental preparation is no less important. A long-distance walk is kind of like a job. We set small goals and developed routines that partitioned the day. On the Camino, we’d wake early and walk to the next village, getting a few kilometers under our belts before rewarding ourselves with a café con leche and pastry. We’d break around mid-afternoon. I’d lie on my bunk bed, feet up, while Barry washed our dirty socks and underwear and hung them out to dry. Then we’d wander around the village, read, write and hang out.

Before we left home on our trips, we prepared by reading other people’s stories, but found their advice didn’t always work for us. For example, we were urged to hire a porter in Nepal to carry our packs, so we did. But within hours, we realized we wanted to carry our packs. We paid him and let him go.

In case things didn’t go as planned, we didn’t set hard deadlines. On the Camino, for example, Barry developed an infected blister and couldn’t walk for a day.

4. There are interesting people to meet everywhere. We enjoy meeting people along the way, especially folks from other countries. In Cusco, we met a Swiss couple who also wanted to hike the Inca Trail. Although we were there in the dry season, it rained three of the four days on the trail. In pouring rain, the four of us clambered up and down the steep, slippery stone staircases built centuries before by the Incas.

Our last day, we passed mist-covered iconic Macchu Picchu on our way down to the village of Aguas Calientes. We barely noticed! We were soaked, and impatient to take off our wet clothes, enjoy our first shower in four days, and celebrate our arrival. Luckily, the next day dawned bright. By the time the sun rose, we were already on the trail, climbing back up the 1000 feet to Macchu Picchu, to gaze at it in all its quiet glory before the tour buses arrived.

On the Camino, we weren’t formally hiking with a group, but ended up being with the same folks who happened to start the same day we did. It reminded me of seventh grade again, with the familiar array of characters, most we liked, a few we didn’t.

Many peregrinos were facing a transition in their lives — a divorce, retirement or an empty nest — and were walking the Camino to reflect on it. We ourselves had just completed a sabbatical and were in the process of moving. The conversations I remember most weren’t about profound insights, but more prosaic aspects. “Sus ampollas son sus pecados,” we heard early on. Your blisters are your sins. Coffee breaks were opportunities to take off our boots and socks and admire each other’s blisters. A Brazilian companion said hers hurt worse than childbirth.

We made a lasting friendship while holing up on a rainy day in a bunkhouse (a small hostel) in the village of Keld, Yorkshire. Hasnah and her dog had driven up from the south for the weekend. The next day, we tromped through marshy fields to a nearby pub. Since then, we’ve seen each other in Britain, Spain and twice in Mexico, where Barry and I live part of the year. I love telling people, “We met while walking across England.”

Where to Next?

So where will we walk next? I’m pondering! I devote delicious evenings considering the alternatives. I read about a limestone area near the city of Alicante, in former Moorish Spain. But another walk, nearer our winter home in Mexico, also calls. This one is located between two of Mexico’s government-anointed pueblos mágicos, in the state of Puebla.

Meanwhile, even on routine strolls around town, walking has become my spiritual practice. Alongside my feet, my mind treads a parallel path, rambling, exploring and wandering. I muse on a line by the 16 century English theologian Matthew Henry, “It is not talking but walking that will bring us to heaven.”