Lyme Disease Advice: Protecting Yourself Against Ticks

The disease is more dangerous for older adults

August 15, 2018. That's when the roller coaster ride began for Paige Persak.

On that day, the Chicago-area schoolteacher looked down and spotted a circular red mark on her right wrist.

"It looked almost like I had a large version of a cigarette burn — perfectly round," Persak says.

Later, a concentric circle would form around it, revealing the classic "bullseye" rash that often (but not always) signals a Lyme disease infection.

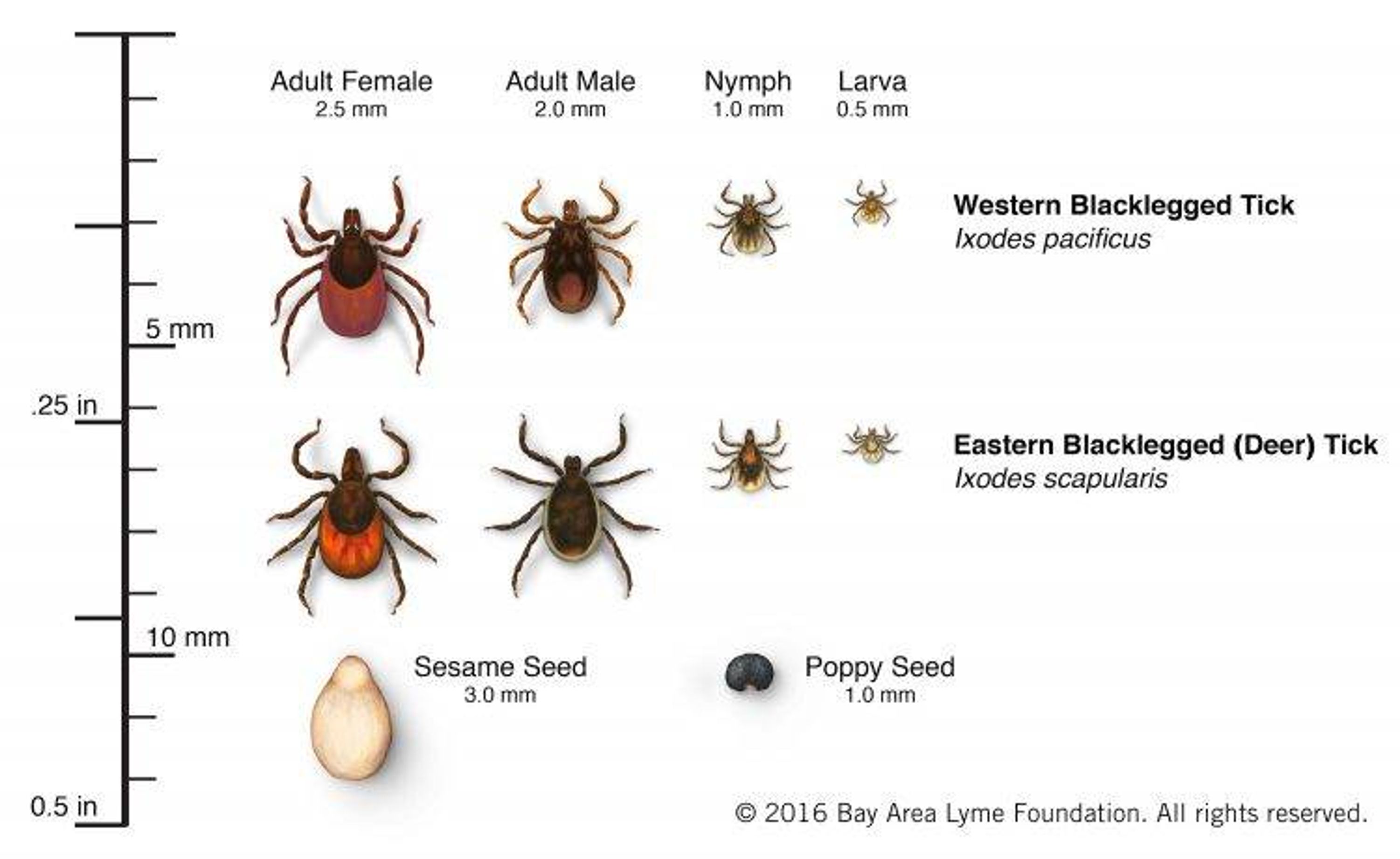

Lyme is carried by blacklegged ticks — small and easy to overlook, even when they're biting as they are at this time of year. In fact, over the next year, Persak would have three tick bites and endure two separate rounds with Lyme. The disease can manifest in many ways, with headaches, fever and joint pain, and can mimic other conditions, such as Alzheimer's disease.

But Persak says she was most overcome with fatigue. "I'm an active, pretty spry grandmother … and I just felt beat and exhausted," recalls Persak, now 69. "My muscles hurt, my legs. I could sometimes just barely get down a couple of city blocks."

Lyme Disease: More Dangerous as We Age

Lyme poses a greater threat as we age and our immune systems are less robust. At least one study in eastern Europe suggests that the usual antibiotic treatments might be less effective for patients over 65.

Persak is convinced that she tangled with the ticks while walking her son's dog in grassy areas along Ten Mile Creek in the upstate New York village where her son resides. The area is a notorious "epicenter," to use her word, for Lyme infections.

But Lyme disease is spreading fast.

"We are increasingly seeing the Lyme disease threat into populations that have not experienced it before."

"I would characterize it as a critically important public health problem that is growing both in number of cases per year and in the geographic extent over which the disease occurs," says Rick Ostfeld, co-director of the Tick Project at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, N.Y., where he's a senior scientist.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that 300,000 people are diagnosed with Lyme disease each year in the United States, a number that is rising. Over about the last decade, the number of private health insurance claims related to Lyme disease has more than doubled, according to a 2019 study.

Spreading Where It Is Relatively Unknown

"We are increasingly seeing the Lyme disease threat into populations that have not experienced it before," warns Ostfeld.

From its origin in the Northeast, burgeoning tick populations have spread the disease into southern Canada, western Pennsylvania and into southeastern states. And Lyme is moving in all directions from its established hotspot in the Upper Midwest. It's now present, to some degree, in all 50 states.

"That's very difficult when you have a population — including the health care providers — that are very naive," says Ostfeld. "They're slow to detect the Lyme disease threat, slow to diagnose, slow to treat, slow to protect themselves. And that's when we have really bad problems in new communities. And that's happening every year, and is likely to continue."

It's likely the warming climate that's driving ticks north, but this does not explain the spread of the disease into southern coastal regions that are seeing Lyme cases for the first time.

Trying to Avoid the Ticks

Persak says she was aware of the risk and tried taking precautions, like wearing long sleeves and avoiding shorts in tick country. She now thinks her habit of pushing up her sleeves on hot days gave the ticks brief, but sufficient, access to her lower arms. That's all it took.

"It's just tough for everybody," she says. "It gets hot in the summer and you're out in the world, and you don't want to live your life in fear. I was just lucky that something showed up in each of the cases that I got a bite. Some people never get a rash and that's a disaster."

Persak also considers herself lucky to find a specialist who effectively diagnosed and treated her ailment. She's avoided some of the more serious complications of Lyme, which can affect the heart and nervous system. But she had to deal with multiple doctors, some of whom dismissed Lyme as a suspect.

Searching for Better Control Methods

Presently, there is no human vaccine for Lyme on the market. (There was briefly, but it was withdrawn after complaints and litigation over claimed side effects.) And the standard test given for the Lyme bacterium is notoriously unreliable.

"Diagnosis continues to be a huge problem," says Ostfeld. "We're using twenty-five-year-old technology to try to diagnose tick-borne disease, and it is far from perfect."

"It's just tough for everybody. It gets hot in the summer and you're out in the world, and you don't want to live your life in fear."

That's why Ostfeld and his team at the Cary Institute are focusing on prevention. In 2017, they began a multi-year field study. Researchers have collected more than 1,600 ticks from backyards in eastern New York and extracted their DNA to analyze it for pathogens. Ticks are not the origin of the disease; they typically acquire it when they bite small mammals, most notably white-footed mice, and then pass it on to us.

Under the rubric of the Tick Project, co-directed by Ostfeld and his wife, Felicia Keesing of nearby Bard College, teams have been trying out methods of suppressing the bugs. These include spraying a native fungus that is non-toxic to humans and other critters, but lethal to ticks.

They're also using specially-designed traps that catch chipmunks and white-footed mice and dab them with a tiny amount of a chemical that is kryptonite to ticks. The goal is to isolate methods of tick control that can be scaled up and eventually reduce actual cases of Lyme.

But funding for prevention research is scarce.

"It's a big problem and it's growing," says Ostfeld. "And unless we aggressively increase our attention to it, it's going to continue to get much worse, at a big cost to the public health."

Protect Yourself Against Lyme Disease

In the meantime, the best way for you and your loved ones to avoid Lyme encounters is to gird yourselves against tick bites. That means:

• Being vigilant in wooded and grassy areas, especially long grasses

• Wearing long pants, preferably tucked into socks, and long sleeves in these areas

• Treating socks and pants with a diethyltoluamide (DEET) or permethrin-based repellent

• Doing nightly full-body "tick checks," including snug areas like armpits and groin

Regarding that last suggestion: Embarrassing though it may be, tick checks are best performed by a partner or caregiver, or with a hand mirror to check the tight spots where ticks love to hang out.

Experts say the sooner you remove a tick, the less likely it is to pass the Lyme bacterium to you. Remove ticks by pulling them straight out with fine tweezers, as close to the skin as possible.

Read More