My Family's History of Estrangement

I’m unsure whether our family pattern stems from heredity, environment or a combination of the two

During a steamy week in July, I spent more time thinking about my paternal grandfather than I had in my entire life up until then.

It was part of my newly assumed role as family archivist — a job I had volunteered for following my mother's death in March, 2023. Her closets contained hundreds of letters, documents and photographs going back more than a century. As each generation died, they had been passed to the next, apparently without much sorting. Archiving refreshed my memories; added footnotes to oft-told tales and introduced some new twists to the family lore.

My interest in the material, most of which I had never seen, went beyond nostalgia. Our family had a history of estrangement that had affected me profoundly. By understanding the dynamic, I hoped to heal that wound. And it seemed to start with my paternal grandfather, William Jacobs.

A Revelation About My Grandfather

For a long time, my father told me that his father was dead. In fact, for the first 20 years of my life, my grandfather lived on the corner of 115th Street and Broadway. I attended Barnard College, nearby, during the 1970s, and for several years overlapped with him in that neighborhood — without realizing it.

For a long time, my father told me that his father was dead. In fact, for the first 20 years of my life, my grandfather lived on the corner of 115th Street and Broadway.

On June 13, 1976, my grandfather died by suicide, jumping from the window of the apartment where my father had spent most of his childhood. I was overseas, so didn't see it reported in the local news. Nor was I present at the dinner table when my father angrily exclaimed something to the effect of, "How could he do that, and make such a mess on the street!" He didn't apologize to my two brothers for the unappetizing description, or for lying to them all those years.

No one shared the information with me when I returned — not that they were told to keep it secret. We siblings were never a united front and didn't generally compare notes. Only after my mother died did one of my brothers describe that evening.

Until I became the archivist, I didn't even know what my grandfather looked like. He and my grandmother, Anne, divorced when I was two. Yet she saved the evidence of how mean, vindictive and unloving he could be. The most striking example involves a valentine from my father's sister, Tina, addressed to my grandfather's office in 1952. Across the top of the envelope, my grandfather scrawled: "Return to sender — Refused."

Had my grandfather, a lawyer, opened it, he would have found an illustration of a mouse peeking out from behind an 8 ball. "From the way that you've been treating me, I'm behind the 8 ball, it's plain to see," the text on the front reads. Inside the message continues, "But we could have lots of fun, we two, if only you would give me a cue."

William Jacobs had cut off his daughter because she converted from Judaism to Christianity. Though he wasn't religious, at the time it wasn't unusual for Jewish people to sit shiva for family members (mourn) who left the faith. Two years later, he announced that he wouldn't go to my parents' wedding if Tina would be there. Few of my father's relatives besides Tina and my grandmother attended.

The Missing Branch of Our Family Tree

That Great Estrangement, as I call it, lopped off an entire branch of our family tree, consisting of my grandfather, his seven siblings and their descendants. When my grandfather died 22 years later, my father and his sister had to consent to the probate of his will, which disinherited them. "I have expressly and deliberately made no provision in this Will for my children Tina Claire Jacobs and Jerry C. Jacobs," it said.

From her deathbed, Flora pleaded, "Jerry, talk to your mother." Thanks to Flora, I got my grandmother back.

During the intervening decades, my father told his children a lie, in which most of our relatives were complicit. But the story lacked details and credibility. During my early childhood, while my father served in the U.S. Army, we lived in post-war Germany. Long before FaceTime, or easy transatlantic phone calls, my parents relied on letters and photographs to maintain our connection with the grandparents back home.

I was curious about the grandfather who never got any play. "Did he want to see me before he died?" I remember asking when I was about four. "No," my father answered brusquely. I felt rejected and hurt.

In a letter sent less than a year after that conversation, my mother described my reaction to the news that Anne was getting remarried, to a man named Harold. "Debbie was somewhat perplexed when we told her she was going to have a new grandpa and wanted to know if Harold would love her 'right away,'" she wrote. "We assured her he would."

If he did, there wasn't much opportunity to show it — this time because of an estrangement with my father's other parent. While I was in elementary school, there was a four-year period during which Anne wasn't allowed in our home, allegedly because she had offended my mother.

That estrangement ended at the urging of my grandmother's older sister. My great aunt Flora was dying of breast cancer in 1967 when my father went to visit her in the hospital and ran into Anne. From her deathbed, Flora pleaded, "Jerry, talk to your mother." Thanks to Flora, I got my grandmother back. Still, the hiatus in our relationship left an indelible scar.

When I was in my early teens, my other grandmother dropped a bomb. "Did Daddy ever tell you his father was dead?" she asked one day when we were in her kitchen together. I nodded. "Well, he isn't," she said. "I suggest you ask him about it." She wouldn't say anything more, which upset me enormously; I didn't feel safe raising the issue with anyone else, for fear it would get back to my father. He had an explosive temper, and I was afraid of doing something that might trigger it.

As events unfolded, the perfect subterfuge emerged. My parents' house was burglarized one summer while I was staying there and they were overseas. I went to the closet where they kept important papers, and looked for their homeowners' policy so I could report the theft. There I came across a page with my grandfather's name on it, indicating that he was 83. I began to tremble, feeling at once betrayed, but again frightened about how my father would react if I told him.

Finally Learning the Truth

When my parents returned, I casually mentioned it in the context of discussing the insurance claim. Without missing a beat, my father said, "That's how old he would be if he was alive." Which happened to be true, since he had died just weeks earlier.

Three years later, when I was 23, my father finally told me the truth. By then I was in law school, and about to leave for a summer job in Los Angeles. My Aunt Tina lived there, and I looked forward to getting to know her better. "There's something I need to tell you, because I want you to hear it from me — not from Tina," was how he broached the subject. "My father wasn't dead, but he is now."

This man held his children as if they belonged to someone else, or stood beside them without any interaction at all. The poses and postures were chillingly reminiscent of my father.

His rationale sounded plausible at the time. "I didn't want my children to worry that I would do that to them," he said, referring to the Great Estrangement. In retrospect, the four-year separation from his mother had already given us cause for concern. Meanwhile, he deprived us of the chance to get to know our grandfather independently and form our own opinions. Given the opportunity, I might have done that. My father made sure it couldn't happen.

In relation to other families, my father often said, "The apple does not fall far from the tree." But that old saw applied to ours, too. While William Jacobs administered corporal punishment with a belt, Jerry Jacobs, one of the founders of the field of pediatric rheumatology, swatted us with his palm. When I cried so hard that I hiccupped, he would yell, "Be quiet, or I'll really give you something to cry about." As a doctor, he showed great compassion for other people's children, but he had no role model for loving his own.

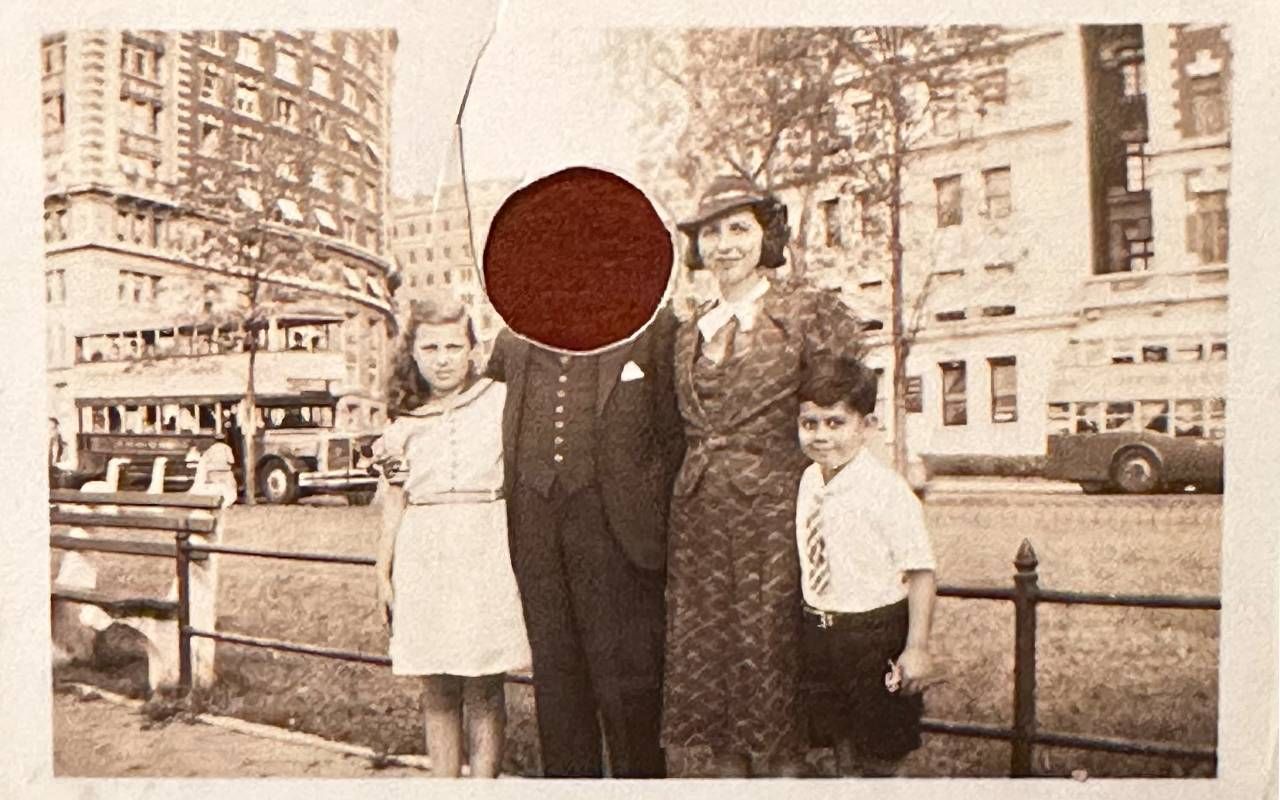

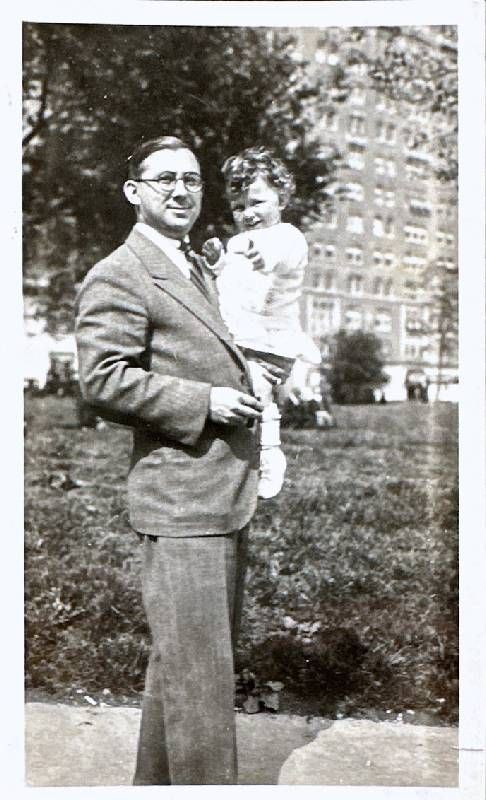

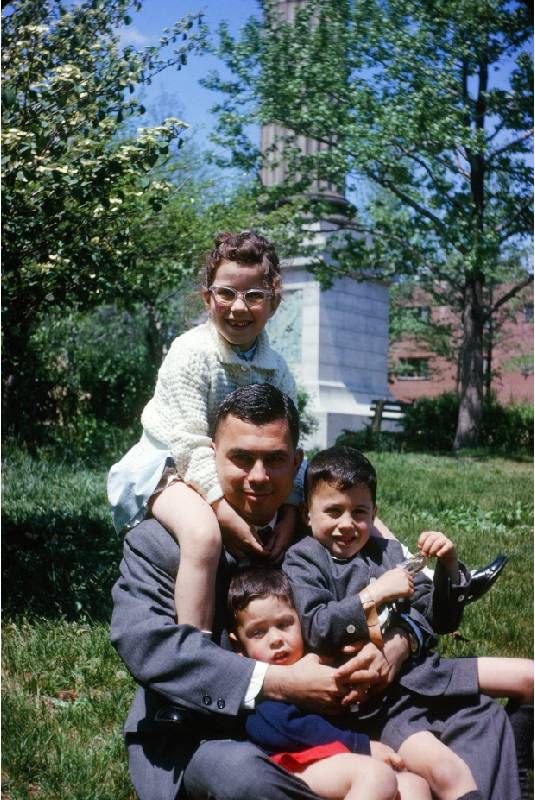

Photos suggest that he was an unhappy child. I looked in vain for a single snapshot from those days in which he is smiling. In a family portrait, taken on Manhattan's Upper West Side, my grandfather's head has been carefully cut out, so that only a three-piece suit is visible, between his wife and daughter. This man held his children as if they belonged to someone else, or stood beside them without any interaction at all. The poses and postures were chillingly reminiscent of my father.

My Aunt's Plea for Harmony

Through a tradition of estrangement, our family created outcasts. Tina, who died in 2015, might have been the worst casualty. Despite multiple moves, my grandmother saved poems that my aunt wrote, over a period of years, pleading for love, family harmony or forgiveness.

Geography, a career as a psychiatric social worker, and a happy late-in-life marriage put considerable distance between Tina and the blood relatives. She had on-again, off-again relationships with both my father and grandmother. I felt stuck in the middle of their gossip about each other.

The final blow came six years before my mother died. In person, she accused me of stealing my father's love letters. I was totally blindsided.

Among my mother's papers, I found a photocopy of a handwritten letter she wrote to one of my brothers in 1985 during his estrangement with my father. "If you cannot resolve your difficulty with Daddy in any other way than by cutting off all communication with him, there is nothing I can do to help and we will all have to live with it," she wrote. "I can only hope that you will be able to see your way clear to resuming a father-son relationship in the future. It would be cruel to think that Daddy, having been cut off by his own father, would have to go through it all over again with his son."

These words seem especially poignant. Father and son resumed a tenuous relationship. By appeasing my father, I avoided a similar rift, but never felt secure with him. For a quarter-century after his death, as my mother experienced prolonged grief, she directed her rage at me; She came from a family that habitually dumped on the daughter. In the Jacobs tradition, she ultimately ended our long-fraught relationship.

The final blow came six years before my mother died. In person, she accused me of stealing my father's love letters. I was totally blindsided. She hadn't ever mentioned such letters. Though I denied the charges, she continued to spread the blame, telling others that I planned to write a book about the letters. Her story was so heinous that almost no one questioned it. One close friend encouraged her to disown me.

Estrangement From My Mother

After that episode, we never communicated or saw each other again. As I pondered what had happened, I read voraciously about estrangement. I learned that often it's the culmination of long-term problems even if, as in our case, there's a tipping point. Most of the literature on the subject, like the social construct, favors forgiveness and reconciliation. So did the relatives and family friends who offered unsolicited advice.

None of that applied to our situation. My mother wanted me out of her life, and might have felt that way for decades. Age just removed the filters on her behavior. Estrangement was my destiny, as it had been for others in my family.

More than anything, I worried about the example this set for my son, Jack, who was very close to my mother. Not wanting to interfere with that bond (as my parents had done to me), I encouraged him to keep calling and visiting his grandmother. That led to some painful discussions. I tried to convey that we have no obligation to continue relationships with people who consistently mistreat us. That's true even if they are family.

Overall, becoming the archivist has been more therapeutic than disturbing.

Jack, now 26, was with me the night my mother died. Upon hearing the news, he threw his arms around me and said, "I'm so sorry about what you have gone through, Mom. I will never, ever do anything like that to you!" I sobbed, then exhaled. Mission accomplished.

I'm not sure whether our family history stems from heredity, environment, or a combination of the two. I've puzzled over why my grandmother Anne, in particular, saved the evidence of so much cruelty. I deeply regret not asking her why she cooperated in my father's lie. I suspect it's because, like all the rest of us, she feared his wrath.

The documents and photographs that she left behind, have helped me piece together the story she might have told. Overall, becoming the archivist has been more therapeutic than disturbing.

Now I wonder whether, while I was in college, I passed William Jacobs on Broadway, at the takeout store 20 feet from where he fell to his death, or at Chock Full 'a Nuts — one of my hangouts. Perhaps there is a mundane moment, deep in the recesses of my memory, when I changed my seat there, to get away from some disagreeable stranger who happened to be my grandfather.