Poverty in the Promised Land

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Matthew Desmond’s new book says poverty is not inevitable and calls on readers to become "poverty abolitionists"

"Why is there so much poverty in America? I wrote this book because I needed an answer to that question."

So begins "Poverty, by America," the latest bestselling book by Matthew Desmond, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 2017 for another bestseller, "Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City."

In his new book, the Princeton professor cites dismal statistics that show America's poverty rate has remained roughly the same over the past half-century, hovering around 12%.

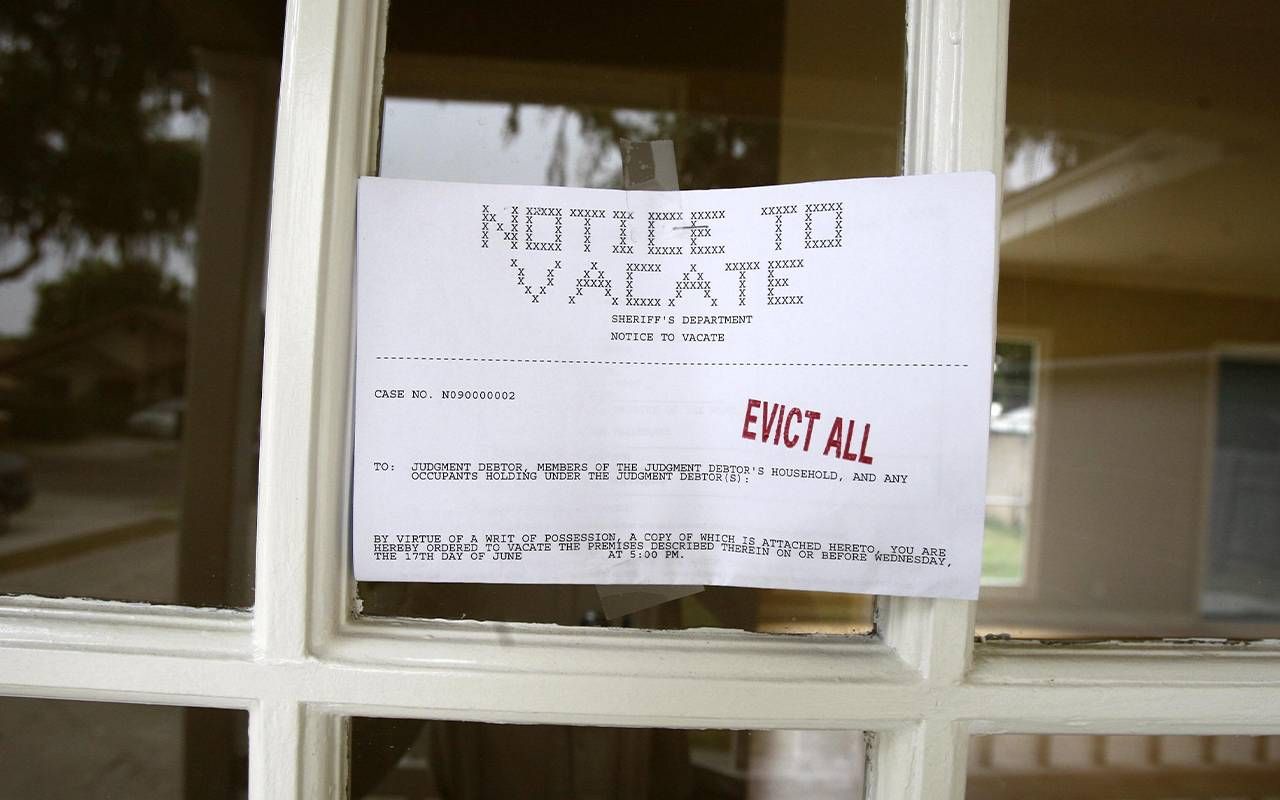

In human terms, that means that more than 38 million Americans, including one in eight children, eke out a living below the poverty level, which is $30,000 for a family of four. Around 3.6 million eviction cases are filed each year in the U.S., and it's estimated that over one million school-aged children are homeless.

"This is who we are: the richest country on earth, with more poverty than any other advanced democracy."

"This is who we are: the richest country on earth, with more poverty than any other advanced democracy," says Desmond.

Desmond has studied the devastating effects of poverty all of his academic life. In his most recent cri de coeur, he sets out to learn why poverty in the U.S. seems so intractable. Along the way he finds a troubling truth: poverty in America persists, he says, because the rest of us benefit from it.

He Found the Problem, and It Is Us

Desmond makes this claim while avoiding finger-wagging (for the most part) and respecting the humanity of people with means. He concludes with an impassioned plea for his readers to become "poverty abolitionists."

Desmond spoke with Next Avenue about his new book — and why all of us should join the movement to end poverty in America.

Next Avenue: It seems the basic premise of your book is that we need to look beyond the poor for answers on how to eradicate poverty. And that, when we do that, we'll discover that poverty in America endures because the non-poor benefit from its existence. Is that, in a nutshell, how you view it?

Matthew Desmond: Yes, that's it. In the book, I quote the author Tommy Orange, who said [about the high suicide rate among indigenous Americans], "Kids are jumping out the windows of burning buildings, falling to their deaths. And we think the problem is that they're jumping."

That's the American poverty debate. For over 100 years we've been focused on the jumpers when we should be focused on the fire.

This book is about the fire — who lit it and who's warming their hands, who benefits. I think it's us.

So that explains the title of your book — "Poverty, by America," not "Poverty in America."

Yes, it's because [poverty] is part of us, a part of who we are. It's a choice we've made as a country and as a people.

I've been writing about poverty all of my adult life and any theory that absolves us — the collective "we" — I've grown suspicious of. I wanted us to own it, to own this problem and see how we're connected to the solutions too.

What exactly do you mean when you say that the non-poor benefit from poverty?

For example, we often like to talk about shareholder capitalism as if it's 12 guys in a smoky Manhattan boardroom. But half the country is invested in the stock market. Don't we benefit somehow — when our portfolios go up — even if that has required some human sacrifice? And most of us consume the cheap goods and services that the working poor produce.

In the end, some lives are made small so others can grow. And we need to write ourselves into that story.

Going deeper on how we benefit: You state that nearly all Americans profit from some sort of government subsidy, from the mortgage interest deduction to 529 college savings plans to child tax credits. You conclude that these are a form of welfare; that they are, essentially, "government handouts." I'd never really thought about it that way.

"We support an imbalanced welfare state, one that gives the most to families who have the most already."

Yeah, I get it. It's a little counterintuitive to think of a tax break as something akin to a housing voucher.

But if you think about it, both the housing voucher and the mortgage deduction cost the government money, they both increase the deficit and they both put cash in our pockets. So if I have a mortgaged suburban home in Westchester (a suburban county north of New York City) and I drive by a public housing complex in the city on my way to work, those are both subsidized.

We support an imbalanced welfare state, one that gives the most to families who have the most already. And then we have the audacity to ask how we can pay for programs that cut child poverty or that ensure that all of us have access to a doctor when the answer is staring us in the face.

LBJ declared "an unconditional war on poverty" in 1964. By 1970 the national poverty rate had dropped from 19 to 12% — but it hasn't budged much since. Is it time for another "war on poverty?"

"What we need is a determination, as a nation, that we can and should end poverty in America."

What we need is a determination, as a nation, that we can and should end poverty in America. That should be our goal. Johnson had that ambition. They weren't playing around, they really wanted to end poverty. We've lost that moral ambition.

Johnson wasn't fighting poverty alone in the '60s. A third of the country's workers belonged to unions, wages were rising, the economy was booming. Today anti-poverty programs have to work a lot harder in order to stay in the same place.

But we know which programs work. [During the pandemic] we took our normal child tax credit and tweaked it a bit . . . and child poverty decreased by 46% in six months!

We need a movement. We need a renewed mass movement for economic justice in America.

A catalyst for LBJ's War on Poverty was Michael Harrington's seminal work, "The Other America." Apparently, some very powerful people read that book. Would you like some powerful people to read yours?

I would! And they are—this book was on Obama's top 10 summer reading list.

But I don't want us to wait for a powerful person to act. I want us to move their hands.

The lesson from the '60s—when we got the War on Poverty, the Great Society, civil rights legislation—is that we would not have gotten those without the labor movement and the civil rights movement. They didn't wait for Congress to get their act together and we shouldn't either.

If there's one thing you would like folks to take away from reading "Poverty, by America," what would that be?

The conviction that we can and should end poverty in this nation of ours. The biggest myth about poverty is that we have to just live with it.

We don't have to live with it.

If you would like to know more about how to become a "poverty abolitionist," Desmond has set up a comprehensive website to help you get started.