As England’s Soccer Season Starts, Its History of Racism Must Be Left Behind

A British Indian who has been the target of racism in the U.K. and the U.S. reflects on what has to change

The start of England's Premier League soccer season on August 13th marked the end of a tumultuous year in the sport. After a year of empty stadiums during the pandemic lockdown, England's national team progressed to the final of the Euro 2020s only to lose to Italy on July 11th, resulting in the racist targeting of Black players who missed the all-important penalty kicks.

It led to five arrests and outrage from politicians and the public alike, sick of the cancer of racism that continues to pollute European soccer. Recent England games against Hungary and Poland have only served to exacerbate things with Eastern European nations seemingly ambivalent about the racist targeting of Black English players by their fans. As a British Indian and former amateur soccer player, it's a culture I am only too familiar with .

The swift condemnation after the abuse of the three players was followed up by arrests, public shaming, immediate job losses and pressuring of social media companies by the British government. More important was the disgust voiced by increasing numbers of the public who have grown up with Black British sporting heroes, most recently celebrated at the Olympics, surely showing that the tide is finally turning against the haters.

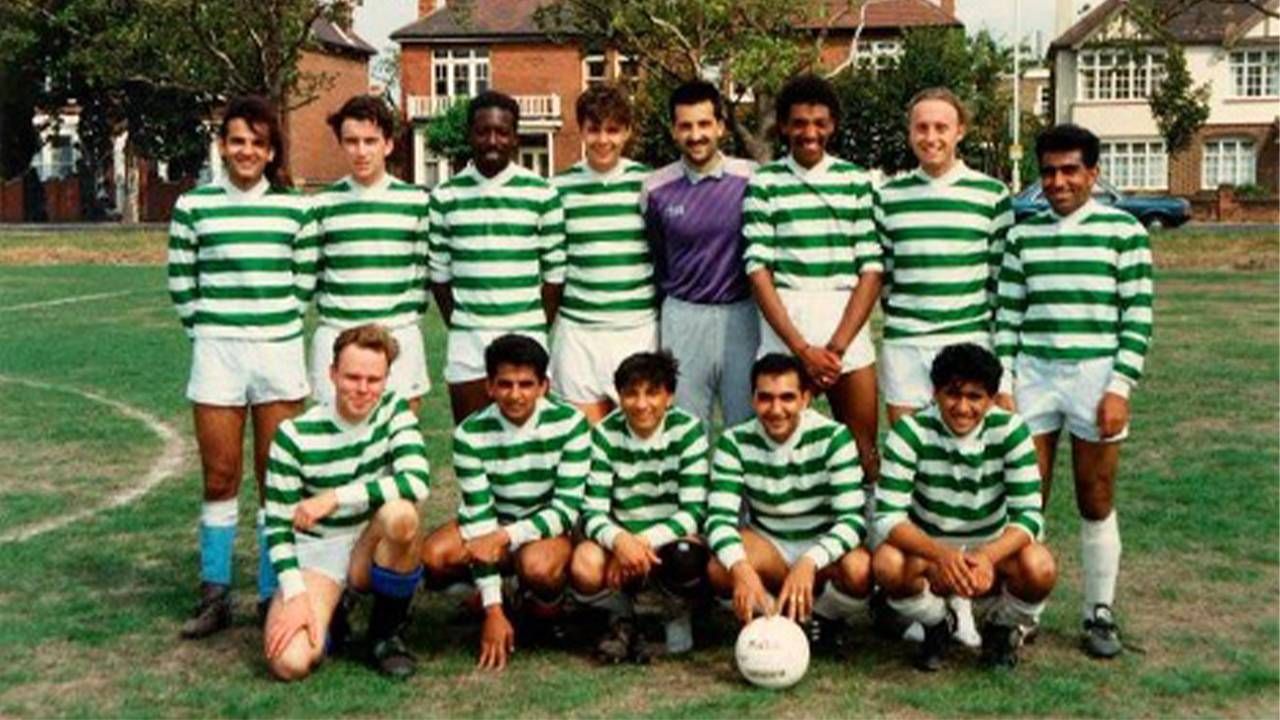

For England's ethnic minorities, the online racism and defacing of murals honoring the players that followed the Euros loss was expected. It was partly why I left the country over 20 years ago. I played amateur Sunday league soccer in one of London's roughest leagues, on a team that was one of the most racially integrated to take the field in any of our games.

I joined the Livis when I was at University and was relieved to find so many talented fellow Asian players. The racism we encountered shocked me.

Livingstone Academicals, as we were called, after the university hall at North East London Polytechnic that some of the players attended, comprised Asian (Indian and Pakistani), white and Black players. We were a fair representation of the neighborhoods in which we lived in Stratford, Leytonstone and Leyton, the former stomping ground of future England captains David Beckham and Harry Kane.

Born in the East End, I grew up in a middle-class Indian family in a quiet, mostly white town in coastal England, about 100 miles from London. I joined the Livis when I was at University and was relieved to find so many talented fellow Asian (Indian and Pakistani) players. The racism we encountered shocked me.

I didn't realize it at the time, but we were trailblazers. Most teams we played against were white. As a mix of Asians, Blacks and whites, we were a United Nations of players doing battle every Sunday morning in the capital's traditional hotbed of racial hatred, East London.

The first Iraq War had ratcheted up hatred against brown-skinned men like me. The insults were hurled in the locker room and on the field. But nothing I experienced compared to the stomach-turning concrete aggregate of slurs my defensive partner, Errol Brown, a mild-mannered architect of Jamaican ancestry encountered.

The hatred wasn't restricted to England, though. We went on a spring tour of Belgium and someone spat in Errol's face. By then, I'd already made up my mind. I was out of there.

No Escaping Racism

I'd spent a lot of time in America before I moved to the U.S. at 26. I was relieved that, in New York, at least, my skin color went mostly unnoticed. That remained the case for decades. I married, had kids and then divorced.

As my children prepared for college, my family encouraged me to consider moving back to England. However, a Brexit-ed Britain had brought out the worst. Hatred seemed to be on the rise and while the same was true in the U.S., I didn't feel it.

That was until one morning a few weeks before the pandemic struck.

I was taking a shower at a YMCA in Westchester, N.Y. where I went before dropping my kids, who lived there, to school (I lived in Brooklyn). I noticed the shower stall next to me was running with no one under it. Instinctively, I turned it off to conserve water. A few seconds later, a man strode in and angrily asked, "Did you turn this off?"

"Yeah, I didn't know you were using it," I said.

"Don't touch my shower!" he yelled with expletives.

Stunned, I looked at the guy, taking him in as men do when threatened. He was white, late 50s, lean but ripped with tattoos. I was also in decent shape, but a few inches shorter. I couldn't let him intimidate me. I shook my head and turned my back, dismissing him. But he wasn't done.

"You Muslim terrorist," he screamed. "Go back to your own country!"

I turned around and looked at him square in the eye, my hands upturned as if to say, "Why did you have to go there?"

There was something immediately familiar about his insult which allowed me to maintain my composure. I had no intention of getting into a fight. I was naked, surrounded by hard tiles and metal.

I was on a tight schedule to pick up my two daughters, yet I knew I couldn't let him get away with insulting me. I decided to report him, which meant delaying my whole day. I walked out of the shower while the man, angry veins bulging in his neck, continued to hurl abuse.

There were two other men in the locker room, both white. I looked over at them, expecting one or both to intervene on my behalf. Neither did.

I wrapped a towel around my waist, put on a T-shirt and went to the front desk to report what had happened. The man there was sympathetic and asked me if I wanted to wait outside until my abuser had left. To do that would prolong me even more. I knew my girls were waiting. It would show I was scared. I wasn't. I was angry.

I'd had a lifetime to analyze how bigotry affected me.

As a teen, I longed to be white. "Paki bashing" was a popular term used when skinheads went around beating up brown-skinned men, whether Hindus — like me — or Muslims. I cowered whenever I saw them, paralyzed by fear. I was only too aware of the dangers of stepping into the wrong neighborhood.

Then, playing for Livingstone Academicals had been the final straw. I wasn't letting racism win, I just wanted to avoid dealing with it. I should have known better.

Bigotry Needs to Stop

I pushed open the YMCA's locker room door. The guy, apparently a regular, was still yelling while someone tried to calm him. When he saw me, he exploded again, this time screaming so loud that members could hear him in the hallway outside.

Angered by my non-reaction, he motioned to punch or head-butt me. I didn't flinch. He was clearly unhinged; if he had a gun, I could be dead. My would-be attacker was finally ushered out of the locker room and I took my shower. When I came out, two cops were waiting for me with questions.

I was glad the assailant was later to be banned from the Y.

In my car, my hands were shaking and I wondered if I was in the right frame of mind to drive my girls. On the way to their mother's, I stopped at a Starbucks, taking deep breaths to stop my heart from pounding. Smooth jazz sounded around me and patrons ordered Frappuccinos and bagels.

I thought seriously about going home, not to a Middle Eastern country as my assailant thought I came from, but to England. When I lived there, however, I'd been told to go back where I came from, too. So where was home? India, where my parents were from? I'd been there twice.

I'd had a lifetime to analyze how bigotry affected me.

Since I'd left, the Premier League had become the wealthiest soccer league in the world, broadcast throughout the globe. Hate is bad news for business. All the top teams are owned by foreign billionaires.

Last season's European Champions League Final was between Manchester City and Chelsea, soccer teams owned by the Abu Dhabi royal family and a Russian oligarch. The last thing they wanted was their clubs, with passionate followings in Asia, the Middle East and Africa, to be associated with racism.

Not that the bigots care or understand. When Chelsea fans leveled anti-Semitic slurs against their London rivals, Tottenham Hotspur, Chelsea owner Roman Abramovitch embarked on a campaign to educate his supporters and wipe anti-Semitism from the stands by handing out lifetime bans to anyone caught spewing hate. Apparently, his fans didn't comprehend that their much-loved owner was both Russian and Jewish.

Change won't happen overnight and it will never be absolute. But until a utopia exists where English bigots don't vent their frustrations against fellow Black and brown citizens, we can only hope that the antiracism uproar evoked this summer means that change won't be far away.