Riding off With a Legacy

A story about women breaking barriers was bigger than my dying friend and me. I promised to see it through.

When I met Linda Back McKay through the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis, I was new to writing, and she had several books published. Yet she asked about my manuscript. Suggested we do a reading together. Connected me with her publisher. Many times in many ways she guided me through the years. She didn't have to take the time to mentor me, but she did.

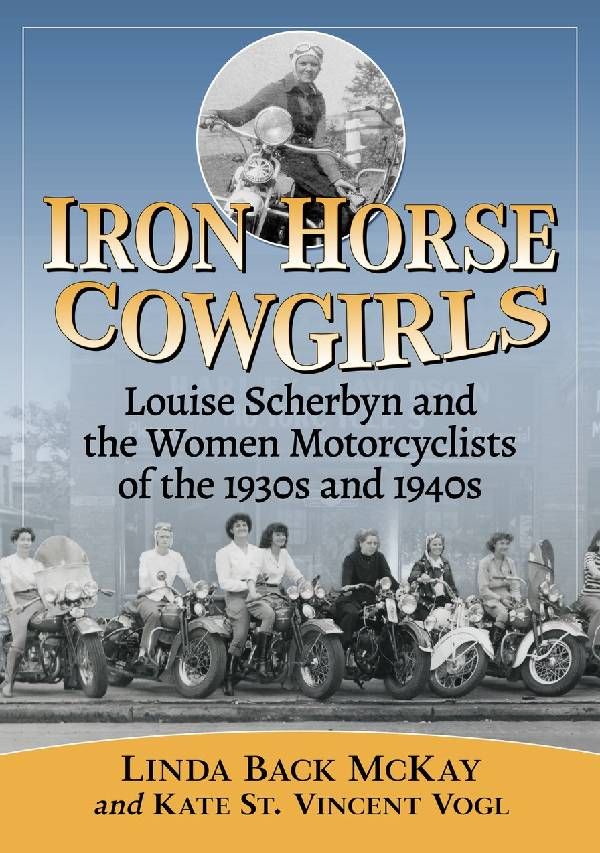

We celebrated her wins, too, like when she got the book contract of her dreams. It'd been too long since I'd ridden my Honda CG125 down unpaved roads around our farm, but Linda continued riding – and writing — about motorcycles. Given the chance to work with the personal photos of the woman who founded the first stand-alone women-only motorcycle association, she said yes.

She always said yes, she told her students. "You always say yes?" they'd ask. "Yes," she'd say.

Saying Yes

Turned out the founder of the Women's International Motorcycle Association (WIMA) also encouraged her followers to say yes — to motorcycle riding. And the thrill of independence.

And in the fall of 2019, from her hospice bed, my friend handed over her whole manuscript.

No other woman in Rochester rode solo when Louise Scherbyn first wheeled her Scout onto the gravel of Maiden Lane during the Depression. Took two years to convince three other women to get their licenses, too. Friendships in their motorcycle auxiliary proved tight-knit and long-lasting.

When someone encourages you to try hard things and you find you can do it, you want help them in turn.

So when Linda found out she had brain cancer, I did what felt right. She needed guidance developing Scherbyn's narrative, something she'd never needed before. And in the fall of 2019, from her hospice bed, my friend handed over her whole manuscript.

It was clear this story about women breaking barriers was bigger than either of us. I promised to see it through.

We didn't know a pandemic would get in our way.

That spring I sorted out what we had and what we needed, scrolling through hundreds of black and whites from Scherbyn's extensive collection — a benefit of working at Kodak. Priceless pics of women in mackinaws and, later, in LeatherTogs. How they clustered around Scherbyn at rallies and picnics. Such impish smiles.

Sorting Through Photos

Many photos we'd had to pull; the women's names and meeting places weren't identified, as the publisher required. Without matching up why and where these motorcycling pioneers had traveled, we didn't have a story.

Neither museum housing Scherbyn's cycles and papers held the answers. Linda had gone looking between treatments. On the way to Waterloo, she'd met up with a woman who'd recognized her mother in a photo Linda posted on Facebook.

The mom had been one of the kids looking up to Scherbyn at a rally. Scherbyn had once belonged to the same motorcycle club auxiliary as the older women in the family, so the daughter brought Linda to the Newark clubhouse. A 1939 photo of Scherbyn hung on the wall. A new archive to explore — only Linda hadn't the strength to stay.

I found the contact info inside her stack of papers. But what could this collection contain that two museums had not?

The contact couldn't say; the mom was sick. As she recovered, I researched what I could. And kept returning to Scherbyn's pictures of rallies and races and picnics and parties. To photos taken during WWII of women posing by motorcycles parked aside a road unfurling into distant hills.

Such a trip taken during fuel rationing must have meant something.

Back at home, I transcribed nearly two thousand pages. Put decades of documents in chronological order.

The mom didn't know why. And she was in and out of the hospital. Yet the daughter was willing to ask her my other questions. It seemed a way for the two to share something they loved.

When Mom gets better, we'll all talk, the daughter promised.

Except the mom unexpectedly passed away.

Thankfully, the daughter remained in touch. Once travel restrictions lifted, she invited me to visit, honoring the connection her mother shared with Scherbyn, then Linda.

Not until I walked in the door did I understand everything she'd pulled together: Crowding the dining room and living room were stacks and stacks of green and blue and brown totes, all lugged out of storage.

Totes Full of Memories

She'd recruited a sister and cousin to help sift through thousands of pages of meeting minutes, club registrations, rally sign-ups, raffle tickets, race records, uniform orders, and travel documents as well as flyers and equipment catalogs and manufacturers' magazines.

The motorcycle club her grandfather had founded was one of the oldest in the country, and they'd kept all receipts, down to the grocery list for the 1942 Turkey Run. And the grandmother and aunts and mom had each held an office in the women's auxiliary. They'd been pen pals with Scherbyn. A wire bin was set out for letters they'd exchanged.

That weekend we drove out to where these women rode and rallied. Where they picnicked, watching nationally ranked riders attempt Keck's hill. The daughter pointed out natural springs where club members stopped for water.

My head was spinning. I'd learned Scherbyn had ridden west for a new national women's auxiliary, then traveled east to reconnoiter manufacturing sites as the first female editor of a national motorcycle magazine. Given the family stories and albums shared, I could identify the women in Scherbyn's photos. Flesh out personalities. I could do this.

We sat at the dining table, reviewing the last stacks of papers, when the daughter cautioned I shouldn't identify the club. Or its location. Or name any members. All the details needed for a book.

I would have protested but saw how her face creased with worry. Hadn't I counseled students through this before? Concerns often arise over how a stranger might depict loved ones on the page.

Considering these women drove hundreds of miles to gather at the fairgrounds, testing how many laps they could go on a tank of gas and how many balloons they could bust on the track proved more their speed.

I had to show how I intended to tell their truth. I had to do this for Linda. For Scherbyn. For myself.

Back at home, I transcribed nearly two thousand pages. Put decades of documents in chronological order. In the archive was indeed everything, including registrations for the All Girls Shows, Scherbyn's brainchild that the grandmother took over. Hall of Fame inductee Dot Robinson even rode in from Detroit since Scherbyn then served as a Motor Maids' officer.

But the gold we found sparkled in letters from housewives and teachers and auto assembly workers and beauticians, all sharing a love of riding and the desire to compete — not in sack races or wheelbarrow races, as the AMA suggested. Considering these women drove hundreds of miles to gather at the fairgrounds, testing how many laps they could go on a tank of gas and how many balloons they could bust on the track proved more their speed.

'This One Is for the Ladies'

Within the hundreds of pages compiled, I highlighted what to consider including. I sent those pages back and shared news articles found about the club, many written by an aunt or the grandfather. The aunt had bested men when testing skills honed by the war's blackout restrictions, like driving with a bag over her head. (Please don't try this at home.) And the mom had stepped into a leadership role, helping Scherbyn through her lowest point. Which led to Scherbyn founding WIMA.

The family well knew the grandfather's accomplishments. The Curtiss Museum kept his effects on display for years. Turned out the women of the family also played an essential role in motorcycling history.

Photos captured how it began, discovering the joy they shared. You can see it in the smile of a ten-year-old riding on her big sister's shoulders at Scherbyn's first All Girls Show.

"I wasn't sure this would happen, with Covid and all," Linda's widower said when the books landed on his doorstep.

Me either.

Yet the effort surely is worth it, to honor those we've cared about and lost. Who made our joy possible.

The sentiment echoing through the daughter's go-ahead: "This one," she said, "is for the ladies."