After 50 Years, I'm Not Keeping This Secret: I've Long Been Diagnosed With Mental Illness and I'm OK if You Know

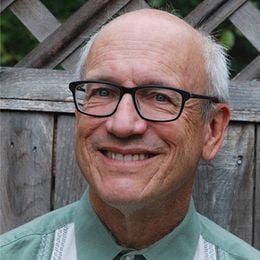

For the first time, journalist Steve Mencher, 71, tells his own story

It's winter quarter, my second year at the University of Chicago. I've been called in to see the dean on this frigid morning, and he is pissed off. As I fidget, he shows me a letter he says I wrote asking for time off from school after an unspecified summer illness. The letter makes no mention of what actually happened that summer and fall, my hospitalization and treatment for mania.

Something is not adding up for the dean, and, sitting in his booklined office, I realize the problem. Told I had to personally request the semester off from school, my father had forged this letter in his neat, looping cursive. It's not the dean's first rodeo. He has examples of my handwriting in his file, and this isn't it.

And so, guided by my dad, I begin a lifetime of trying to hide my mental illness from the world.

And so, guided by my dad, I begin a lifetime of trying to hide my mental illness from the world. In this case, dad was afraid I'd be kicked out of school for being crazy. In his eagerness to help, he jeopardized my standing at school by forging this document and lying about my health.

It's no longer a permanent mark of shame to admit struggles with mental illness. But stigma — the judgment of society that those with mental illnesses are different, weak and a threat to the order of things — has not gone away. In my case, this essay is my first real attempt to let go of a secret I've kept for more than 50 years.

Letting Go of a Secret

My wife wrinkled her nose when I told her about this assignment. Perhaps that's because my diagnosis of manic-depression, officially known as bipolar disorder, wasn't a secret for her; I shared it on our first date 38 years ago. And I've dropped public hints in various places for decades. But she soon understood that holding this in during my career has taken a toll. Finally, now that I'm 71, the time seems right for a fuller look at how stigma has shaped my life and career.

My illness first showed itself with that episode of mania in my late teens. After finishing my freshman year of college, I camped out on a river in Northern California with a motley crew of young people — eating government cheese, basking in the sunshine and shivering in the fog. Along the way, I became convinced that I should star in the forthcoming screen adaptation of "The Godfather." Untethered, I stalked a resident of the town of Mendocino because I imagined he could help me contact the casting director for the Coppola epic. Instead of helping me edge out Al Pacino to play Michael Corleone, he called the cops.

Hospitalized at Mendocino State Hospital, I was heavily medicated with Thorazine in the fashion of the time. Thorazine is like chemical shock therapy, a two-by-four that whacks your brain back to "normal." Medicated and sedated, I flew home to New York City, and a short stay in a hospital upstate. I made my way back to college in the winter quarter of my sophomore year.

That year I nearly flunked two classes, escaping with a pair of "gentleman's D's." Nobody would have known why I showered only every few weeks, and, like Pigpen, was followed by a dark cloud.

After my meeting with the dean, and letting him in on the secret, he mandated that I see a therapist every few weeks. I'd go downtown on the train, sitting silent in the cozy office for the best part of an hour. Friends and faculty were left to guess about that summer's crack-up. That year I nearly flunked two classes, escaping with a pair of "gentleman's D's." Nobody would have known why I showered only every few weeks, and, like Pigpen, was followed by a dark cloud.

By junior year, I was back on track. I finished college on time, was chosen by my classmates to address them at graduation in stately Rockefeller Chapel, started grad school at 20, and finally took a break from school at 21.

Banned From NPR

Fifteen years later, I was a producer at NPR's "Performance Today." After budget cuts eliminated my full time work at this classical music show, I was hired regularly as a freelancer.

During that period, my older brother died suddenly. My grief turned to mania, and I began to act strangely. I convinced the editors of my old show to let me interview the top executive at Carnegie Hall. German and famously autocratic, he bristled when I corrected his English and treated him without the respect he expected and deserved. The NPR engineers who were helping me record the interview reported my odd behavior to my supervisors.

Around that time, I asked a friend at NPR to help me record an improvised dirge for my late brother, and I sobbed loudly as I caressed the nine-foot Steinway in NPR's best studio.

My colleagues ran out of patience with my behavior and told my wife that I was barred from NPR's Washington headquarters. So, where does stigma fit in to this chapter of the story?

I was marked as unwell and a danger to the strict professional atmosphere necessary for getting something excellent on the air every day.

For one thing, my expulsion from NPR felt like shunning. I was marked as unwell and a danger to the strict professional atmosphere necessary for getting something excellent on the air every day. Mental health stigma brands people as disruptive and scary, rather than on a continuum between health and illness.

For the first time in more than thirty years, as I revisit this, I remember that I was given a chance at redemption — if I produced a letter from a psychiatrist affirming that I was "better." But at the time, it felt to me that there was no empathy for my sickness, no sense that I was in pain or suffering, as there would have been if I had cancer or heart disease. And some of my former colleagues would, from that time forward, look at me as damaged.

I'm not sure what could have been different, but I can imagine an approach that would have been more supportive, helpful and healthy for me without exposing the workplace to further turmoil.

Struggling at AARP

Years later, I went to work for AARP as a radio producer. In my first months, I breezed up and down the halls in our little media center, whistling, smiling and blissfully unaware that my boss was steaming about my jolly behavior. I'd show up to meetings of other producers and editors unaware that I was expected to be silent for a decent interval before jumping in to the discussion. On fire with creativity, I crafted an award-winning radio program about veterans of the Iraq and Afghan wars coming home with brain injuries.

I would have to admit that I was clinically depressed, unable to function. I couldn't do that, for fear the admission would end my job and leave me unemployable.

In my first job evaluation, my boss dinged me for my behavior, especially the whistling. Yes, I was slow to sync with the culture, but that was also me in a hypomanic phase, living the slightly loopy, energetic and creative highs which mark one parameter of being bipolar.

As my supervisor continued to bear down, I began to sink. She piled on detail-oriented work, set outrageously unmeetable deadlines. Around this time, a small tornado passed over our home, throwing three huge white oak trees onto my newly constructed home studio and piercing our roof.

We moved out to a rental while the house was fixed. Increasingly, I struggled to wake up, shower and get to work each day. For the first time in my life, I was tempted to ask HR about going on short-term disability, but in my depression, this seemed impossible. I would have to admit that I was clinically depressed, unable to function. I couldn't do that, for fear the admission would end my job and leave me unemployable.

Instead, I stumbled forward. My doctor prescribed various anti-depressants, and eventually I found myself right side up. Would the path have been smoother if I admitted my illness, got more-focused treatment and received disability benefits while I healed? There's no way to know what the absence of stigma looks like when fear is all you can see.

And even in my late sixties, my lifelong pattern was unchanged: I bore my illness quietly, recovered fairly quickly.

After a few more years at AARP, I felt bold enough to hide in plain sight. I wrote about bipolar illness and suicide in a quiet corner of our website, with the subtext that these were my personal stories. But I never discussed these issues with my supervisors, and only a quiet "attaboy" from a colleague marked her as someone who shared and understood my symptoms and diagnosis.

Last Acts

After AARP, I worked my way back to public media, and held some great jobs as a producer, writer and news director. During my most recent public media job, I suffered a medication-induced bout of crippling anxiety. And even in my late sixties, my lifelong pattern was unchanged: I bore my illness quietly, recovered fairly quickly.

Without sharing any of the details of my mental health struggles, I went back to work, winning awards and creating notable stories and podcasts. My fear was the same as it had been at the University of Chicago, NPR and AARP: if I shared the truth about my condition, I would not be allowed back to work; I would be an outcast.

I don't know if things would be better for me if I was a young person today; perhaps they'll be better for those growing into the challenges of mental illness and the stresses that compound those challenges, as people talk more openly about stigma and how to combat it.