Tackling Loneliness

Americans are still less connected and experiencing loneliness — how can communities help?

When the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 virus to be a global pandemic in March 2020, Julianne Holt-Lunstad wondered about the long-term implications that measures would have on the issue of loneliness and mental health.

Front and Center Issues

Holt-Lunstad, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University, has researched the issue for decades and served as the lead science editor for the recently announced advisory by U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Vivek Murthy, declaring an epidemic of loneliness in the country. In a telephone interview, Holt-Lunstad said the timing of the release of the advisory was apt considering many Americans' overall experience with loneliness during the pandemic.

"Given the pandemic was exacerbating the problem, the timing was apt in the sense that we all had a personal experience with the kinds of effects that loneliness can have and how it feels, whether we experienced it personally or know someone who experienced it," Holt-Lunstad said.

The advisory, released in May 2023, indicated that approximately half of American adults reported having measurable levels of loneliness, which can increase the risk for mental health problems. Additionally, the lack of connection can lead to an increased risk in death in levels that are equal to smoking every day.

"We are seeing a picture of trends that Americans are becoming less connected and this began well before the pandemic."

In an interview with NPR, Murthy, a previous Next Avenue Influencer in Aging, said that loneliness was paramount, and is not a problem specific to the U.S. population.

"In the last few decades, we've just lived through a dramatic pace of change," Murthy said. "We move more, we change jobs more often, we are living with technology that has profoundly changed how we interact with each other and how we talk to each other. And you can feel lonely even if you have a lot of people around you, because loneliness is about the quality of your connections."

Holt-Lunstad says the data in the advisory backs it up.

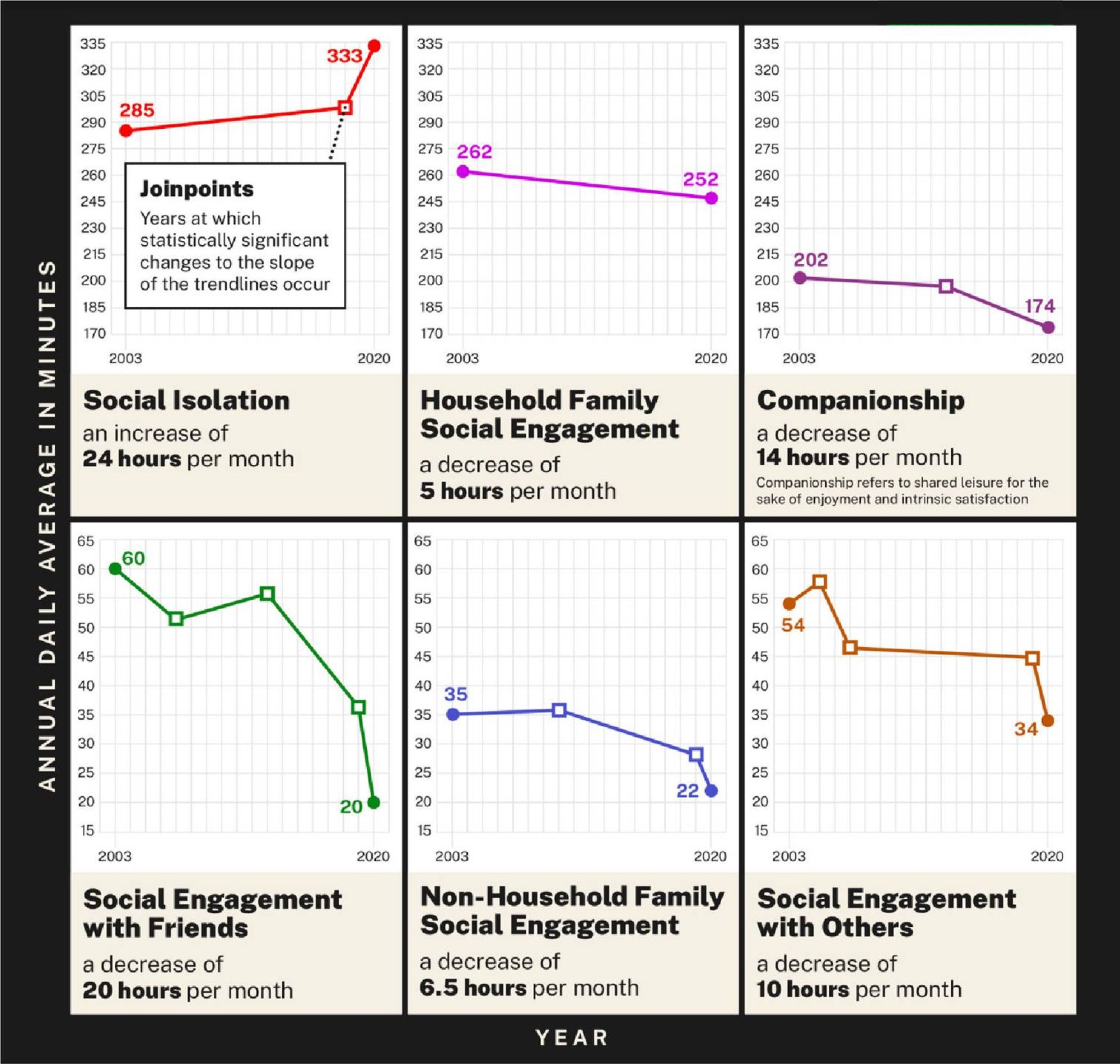

"There are a variety of trends that suggest Americans have become less socially connected," Holt-Lunstad said, "and this began well before the pandemic. We presented data on how people use their time from 2003-2020 and roughly two decades of data shows that people were increasingly spending more time in isolation, less time with family and friends (both inside and outside the home), and socializing with others. There is greater awareness because of the pandemic but this is not a unique problem to the pandemic."

The issues presented were clear — yet, experts, including Arianna Galligher, a licensed independent social worker and the Associate Director of the STAR Program at The Ohio State University's Wexner Medical Center, agree that it took the pandemic to bring them front and center.

"As the world continues to adapt in response to an increasingly digital landscape, the mechanisms by which we connect and build relationships with one another have also shifted," Galligher said by email. "At our core, human beings are social creatures, but it's often difficult to know how best to show up as our authentic selves in virtual spaces."

"Struggle breeds fear, and fear inspires dichotomous thought processes in which people make snap judgments and draw 'all-or-nothing' conclusions,'" Galligher said. "So, things are either good or bad, right or wrong, safe or a threat. While this way of thinking is quite useful when we're actually facing down a threat to our well-being, it's not very conducive to producing empathy, compassion for others or self-compassion. If someone is reasonably certain that they'll be faced with judgment or ridicule if they discuss what they're struggling with, they will often go to great lengths to conceal it instead."

Holt-Lunstad says the pandemic has presented an indirect opportunity to reduce the negative bias of talking about one's mental health.

"During the pandemic, when isolation was a shared experience, and was due to other kinds of forces, people were open to talking about it," Holt-Lunstad said. "As we try to think about reducing the stigma, helping people recognize there are a myriad of factors that can contribute to isolation and loneliness is key to move forward."

In addition, Holt-Lunstad says, loneliness has long been treated as an issue that is based on emotional well-being instead of physical health and that too much responsibility has been put on the individual to solve the problem, rather than creating solutions as a society to help individuals where issues are beyond their control, be that city design and community safety or economic and educational prosperity.

Holt-Lunstad encourages a "whole of society" approach, which borrows from the approach taken by the World Health Organization that all policies can have health implications. That approach means that every part of society as a role to play, be it the local, state and federal governments, or employers, industry and individuals themselves. Holt-Lunstad adds that by addressing loneliness through this multifaceted approach, it could help with other issues simultaneously.

"All must philosophically agree that healthy, authentic connection with others is an important mechanism for cultivating meaning and value across the life span."

"This should not be seen as competing with other issues, but something that could help with these pressing issues," Holt-Lunstad said.

Indeed, as Galligher says, in order for this multifaceted approach to work, there has to be common ground.

"There are opportunities at the individual level and family level, at the workplace and community level, and at the societal level," Galligher said. "However, all must philosophically agree that healthy, authentic connection with others is an important mechanism for cultivating meaning and value across the life span."

However, for it to truly work, both Galligher and Holt-Lunstad say the culture needs to adjust. For Galligher, however, in order that the message for change has been received, the norm change would be broad.

"Change will take shape to manifest in big and little ways," Galligher said. "More people will make eye contact with one another when they're out in public (at the grocery store, passing each other on the sidewalk, etc.). Families will establish limits related to screentime. Neighbors will make an effort to get to know one another, even a little bit.

Organizations will establish workflows that leave space for colleagues to connect as people. Communities will create and maintain safe, inviting spaces for people to gather. Societal attitudes will shift so that people are more likely to default to curiosity and compassion rather than judgment when faced with an issue that they don't understand."

Galligher emphasizes that psychological safety is key to fostering meaningful connection. This is especially necessary so individuals are not doing the bulk of the work of improving societal structures in response to the issue of loneliness.

"Systems and societies can create psychologically safe environments by adopting a 'just culture' in which honest, human mistakes are forgiven and seen as opportunities to learn (or as Maya Angelou put it, "when you know better, do better")," Galligher said. "Conversely, people are held accountable for willful misconduct or gross negligence."

Ultimately, Holt-Lunstad says, societal norms must support any change that comes.

"We can make recommendations on how people can make changes in their lives or make more socially connected communities," Holt-Lunstad said. "But if the norms don't support that, then we're not going to see the kinds of changes that we would expect."