Unexpected Lessons of Terminal Cancer — Talking About Death and Life

Two renowned journalists, Rod Nordland and Richard Harris, share a diagnosis of Glioblastoma. In this conversation, they talk about living with the diagnosis, remaining positive and the impact of love and support.

I could have kept my diagnosis in November in the family. But when the pathology report from the Mayo Clinic said Glioblastoma (GBM —terminal brain cancer), I didn't want to spend what time I had left hiding the elephant in the room. I felt fine, wasn't depressed, but was simply looking for some inspiration. So I waited until the holidays were behind us and sent a note just after New Year's to friends and extended family. It didn't take long for the inspiration to materialize.

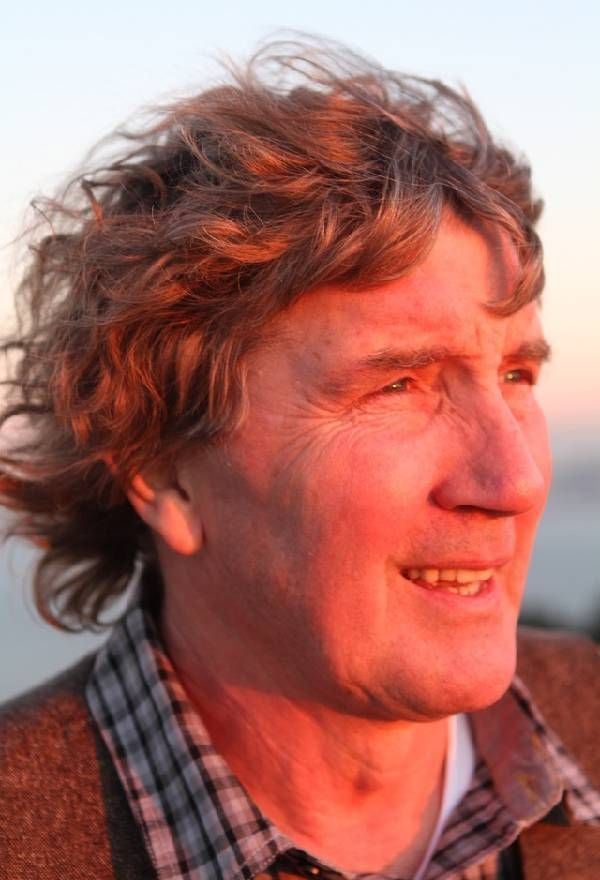

Among the friends who received my message, journalist Mark Whitaker sent word that his former colleague at Newsweek, now at the New York Times, longtime foreign correspondent Rod Nordland, had also received a Glioblastoma diagnosis. His came after being medevacked to New York following a seizure in India.

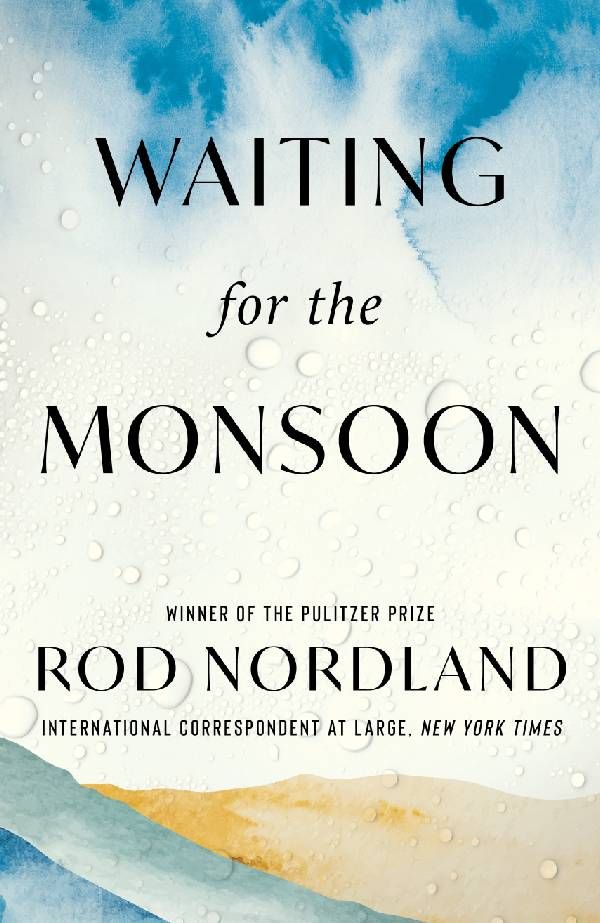

But Nordland has defied the odds and is nearly five years beyond his diagnosis. For the 14,490 diagnosed with Glioblastoma in the United States each year — Nordland and I included — there's no way to know how much time we have. But one of the virtues of Nordland living well past the median life expectancy stats is it's given him time to capture his journey in a stunning book and live to see it published. Nordland wrote all of "Waiting for the Monsoon" in longhand while undergoing harsh treatments. It became what he calls his "adventure of the mind."

"I think most of my doctors would feel that it's partly that they're so wonderful and partly because I have such a positive, optimistic attitude. And I've kind of refused to accept that my death is inevitable on this."

For me, this was an opportunity to see how a Glioblastoma patient had exceeded the survival stats, not by months but years. It is not only inspiring, but provides hope. Nordland's book begins with his essay first published in the New York Times in 2019 headlined "Waiting for the Monsoon," now adopted as the title of his book.

The day his essay ran in the Times, Nordland, a Pulitzer Prize-winner, received a note from David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, calling him "the foreign correspondent's foreign correspondent." And added, "You have always been one of those reporters whom everyone who knows anything looks up to. And your essay today will outlast the lot of us."

While Glioblastoma has been diagnosed since the 1800s, it was the deaths of Ted Kennedy, John McCain and President Biden's son Beau that perhaps most recently put the fatal tumor in the headlines.

Here's a condensed conversation of Nordland and his partner Leila Segal talking with me over Zoom from New York:

Richard Harris: Rod, you've provided the inspiration I was seeking. In four months, you will hit the five-year mark past your glioblastoma diagnosis. And as I understand it, only 7.2% of the glioblastoma patients live five years beyond their diagnosis. Why do your doctors believe you are such an outlier?

Rod Nordland: I think most of my doctors would feel that it's partly that they're so wonderful and partly because I have such a positive, optimistic attitude. And I've kind of refused to accept that my death is inevitable on this. There's actually medical research that shows that people who refuse to accept a terminal diagnosis, even when the medical evidence is solid, they have much better outcomes than people who just say, oh, well, there it goes. And also, people who participate in clinical trials, whether the trials are successful or not, the mere act of signing up for them gives you a better outcome than if you didn't. I've kind of had fun being terminally ill, to tell you the truth. I find a lot of funny moments, and I just play to them, you know?

Well, maybe that's the secret to your survival ...

Rod: You know, people ask how I am. I say, well, I have terminal cancer, but otherwise I feel fine.

I have made similar cracks about my terminal brain cancer.

Rod: If someone says, 'Can I put you on hold for a moment?' I say, 'Actually, no, you can't. I have terminal cancer, and I don't want to spend what little time I have left listening to really bad hold music. So please just put me through.' And that usually shocks them into compliance. How's your latest scan, Richard?

It's pretty good. After my six weeks of radiation and chemo pills, I was on a four-week break. It's part of the standard of care. I had an MRI, and the scan looked pretty good from what the doctors said. But what's been hard to process since I got the news of the diagnosis in November is how on the one hand, I've had no pain or discomfort, tolerated radiation and chemo very well — for which I'm grateful — and yet I, like you, live with an aggressive tumor that can end our life.

"So many people just can't deal with somebody who's sick. They can't face it. And so they just ghost you."

Rod: GBM is like that. It's sneaky. Doesn't hurt till it kills you. It sneaks up and that can happen any time. I had a friend who made it five years and then in her fifth year, she had three recurrences requiring brain surgery and then died. So you know it's a life sentence, this disease. It's incurable. But it's treatable. It's kind of a Sword of Damocles hanging over your head for many years.

Leila Segal: Every two months Rod has a scan. And in the beginning, we couldn't understand how we could live like that, but we have. You just adapt somehow, you know?

Rod: Some of the habitations are unpleasant, like getting used to being ghosted by family and friends because so many people just can't deal with somebody who's sick. They can't face it. And so they just ghost you. And it's really a common phenomenon.

And these are members of your family?

Rod: Family and friends. Yeah.

When you first got the glioblastoma diagnosis, you were back in New York by this point, correct?

Rod: Yeah, in the hospital.

Did you ask your surgeon Dr. Steig how much time you had left, knowing that it was a fatal diagnosis?

Rod: He immediately said, 'Your mean life expectancy is 14 months. And tell your family. Tell your friends. It's incurable, it's untreatable, that it will kill you.'

And I had to laugh at that point in the book because your surgeon was anything but subtle. It wasn't simply zero bedside manner, but zero toilet manner. As I remember, you were on the toilet, and he did not want to wait until you finished. And he proceeded to give you a real in-your-face kind of assessment of what was going on.

Rod: Well, I did ask him to be honest with me. The doctors in India had just lied their asses off. They didn't even tell me I had a tumor. They wanted Leila to tell me instead of telling me themselves. So I was sick and tired of this bullshit from doctors. And I'm gonna ask them to be frank.

We had very different early experiences that would lead to glioblastoma diagnoses. You were jogging in 120-degree heat at 10 a.m. in New Delhi's Lodhi Gardens when you collapsed with your epileptic seizure. And before the New York Times medevacked you back to New York to the Weill Cornell Medical Center, you were mistaken for a cadaver. Who shared the toe tag story with you?

Rod: One of the staff from the bureau of the New York Times, who would come in to keep me company. They said I was toe tagged with a sheet of paper that identified me as an unknown Caucasian male, age 47 and a half. I learned I was in a coma at that point, so the crew from the morgue took me to be dead and put me with the rest of the cadavers. It made me feel good because 47.5 was far less than my actual age. It was only a few days till my 70th birthday. What I never understood, though, was the half. 47 I can understand, but why 47.5? It's always mystified me.

"You need to challenge everything the doctors say. Question it. And often look for second, third, even fourth opinions in terms of your treatment plans."

Oddly, both of our adventures began on July 5th, yours in 2019, mine in 2023, and each of us was about to turn 70 when we got the news. You in days, my 70th was still two months away. [First sign of trouble was my left eye that experienced odd vision then went dark completely over several weeks in July. The rest of the summer and early fall was devoted to why my left eye ceased to work until a biopsy revealed a Gioblastoma in November.] And to add to the intrigue, my doctors at Georgetown Hospital where I was treated had rarely had a patient like me where the glioblastoma originated in the optic nerve. So apparently my GBM is very rare. What have you learned in nearly five years living with your glioblastoma that you might want to share with me and other members of the GBM club, as it were?

Rod: That you really have to be your own patient advocate, and hopefully you'll have somebody who can be there for you, too. But you need to challenge everything the doctors say. Question it. And often look for second, third, even fourth opinions in terms of your treatment plans. One of the things you have to realize about a cancer like this is that it's disabling. You're a disabled person as much as if you had your legs cut off. You know, in 100 different ways.

Leila: You have to be brave. That's why, in my opinion, Rod is successful because he's brave. He's not afraid. You know, lots of these surgeries and treatments require a lot of courage because they come with risk. And this needs incredible discipline. It's tiring. It's exhausting. It's not normal life.

My doctors have told me, as I'm sure yours have told you, that a positive attitude can only lengthen your life. For me, it's been easy to be positive because other than the difficult diagnosis, I've been feeling fine. I've tolerated my first round of radiation and chemo pills — even the second round of higher dose chemo —so it's hard to process why I should feel depressed. How do you keep YOUR positivity through your ups and downs?

Rod: It's just my nature, I guess. And I think it's the journalist in me. A part of me kind of enjoys the experience, even though I know it may well kill me before my time. It's a tired cliché to compare cancer to a war or a battle. But it's similar in so many ways. For instance, I don't really like talking to people about glioblastoma unless they also have glioblastoma, exactly the way soldiers are. You know, soldiers very rarely want to speak about their wartime experiences, except with other soldiers who've been through the same thing.

Who can relate to it.

Rod: So that's a very similar trait. But also covering war is really interesting. It's a lot of complex human dynamics at play. And that's also true of my decisions and the people the translators use. It's very stimulating. It reminds me that I'm alive.

Leila: You know, it's very intense. And also, we meet such incredible specialists, the top of the field, brilliant people, and their attention is focused on us. So it's kind of thrilling. It sounds wrong to say it, but there's a lot of emotional reward and intensity as well.

You write in the book that 'this is hard for people to believe or understand, but glioblastoma has proved to be the best thing that ever happened to me — maybe even if I don't survive it, but especially if I do. I have come to think of my tumor as my friend, my teacher, my mentor and especially, my gift.' Explain.

Rod: Well, it's just made me a better person. I've managed to reconcile with a lot of old friends, with my family, and especially with my children, and I think I saw them because of the tumor. And so I kind of feel grateful for it. I think it's also made me much more sensitive and compassionate. (To Leila) Would you say so?

"I've managed to reconcile with a lot of old friends, with my family, and especially with my children, and I think I saw them because of the tumor."

Leila: Definitely. I think you had that sensitivity, but you suppressed it because of your tough persona in the world, and it's just allowed you to experience vulnerability. That's what I've seen between us, for sure. To experience love, actually.

You also talk about your "second life" and quote the French neuroscientist David Servan-Schreiber, who survived glioblastoma for nearly two decades:

'The approach of death can sometimes lead to a kind of liberation. Wouldn't it be far worse to have no reason to be sad at that moment of parting? And the finality of that moment forces us to recognize the profoundness of our love.'

Servan-Schreiber is my GBM hero. How do you compare your first life with your post-diagnosis Second Life?

Rod: My children, most of all, because I was quite estranged from them in the process of divorcing their mother. And for a long time, they wouldn't speak to me or visit me. And when I got sick, they came back, and I'm actually kind of grateful to my tumor for that.

Leila: It's really changed, I would say from my observation, it's very much 100%. It's blossomed. I think it's that relationship with your children has become what it always could have been.

Toward the end of the book you bring up something that says something about you — you still make your bed every morning. Even when there were people to do it in hotels and hospitals. How long have you been making your bed? Is it the discipline of doing it daily that gives you strength and why is this important to you?

Rod: Yeah, I think that's right. I've been doing it my whole life. Pretty much. And my son's like this too. He always makes his bed and he, like me, will rearrange the furniture in a hotel room to our liking. It's just the discipline is good. It takes a lot of discipline. I mean, I keep up a pretty vigorous program of exercise, and I think I do a pretty good job.

Leila: He's extremely disciplined. Even when it's rough for him. And he does the exercise every single day. Amazing.

"Every aging man should do sit to stand exercises. They're just unbelievable. They develop your quads and your abs and your stability and they're great exercise."

What's the main exercise that you do?

Rod: Sit to stand. Every aging man should do sit to stand exercises. They're just unbelievable. They develop your quads and your abs and your stability and they're great exercise.

And how many do you do?

Rod: I do 170 a day.

My goodness.

Rod: That's correct because my left leg needs extra work and a hundred for both legs.

You say you discovered wonderful dividends from your brain tumor, including this renewed family life. But you and Leila were just beginning a new life together. And then this happened. This has to be a tough time, but having Leila by your side must be an enormous support for you.

Rod: Yeah. And she's written her own book about this experience "You Came Back" (forthcoming) because she's a victim of my disease as well as me so she has a unique perspective on it. We decided to face it together and grieve together. We had a friend whose husband had died of Glioblastoma. And the one thing she regretted was that they didn't take the time to grieve together when they could. So we've taken that to heart and done that.

Leila: But we also embraced the experience as a couple. I had to make that decision — do I stay with him or do I leave him? It wasn't easy in the beginning because we lived in England. But Rod came to the U.S. to be diagnosed and, once we made that decision, we both embraced it. And we often talk about how it's brought us much closer. It's like a very speeded-up version, the 20-year marriage.

Rod: That's a good way to put it. Do you have a Leila in your life?

I do, my wife of nearly 44 years, Kit. I wrote about her when I sent my Glioblastoma note around, and I couldn't agree more that like your Leila, my Kit has been with me every step of the way. Her support has been critical.

Leila: Well, the thing that shocks me is that some people leave people when they're diagnosed.

Yeah, that's so sad.

Leila: And I've heard it's very common.

Rod: It does impose a huge burden on them. You know, so you can kind of see that one.

Leila: That's life, isn't it? If you don't choose this, then something else will come and get you. So why not choose the life that you've been offered? Honestly.