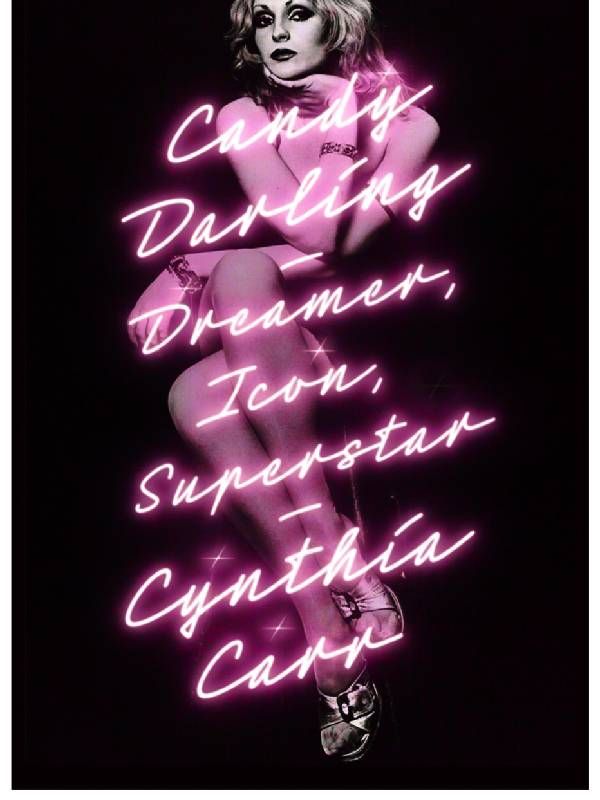

The Glittery Life of Candy Darling

Identifying neither as a drag queen nor a ‘pre-op transsexual,' Candy Darling, the Warhol superstar, was ahead of her time in just wanting to live as a woman

In the late 60s and early 70s, Candy Darling seemingly enjoyed all the trappings of being an Andy Warhol "Superstar" in New York City.

She appeared in seminal Warhol films "Flesh" and "Women in Revolt," made the scene at the nightlife hot spots of the era and acted in edgy, off-off-Broadway plays, inspiring songs by the Rolling Stones ("Citadel"), Velvet Underground ("Candy Says") and Lou Reed ("Walk on the Wild Side").

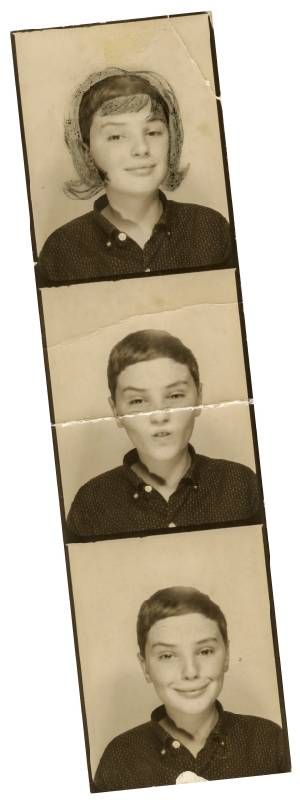

Even during the height of her fame, however, Candy, a transgender woman who was born James "Jimmy" Slattery, didn't have it easy. She could have gotten arrested in New York City simply for walking into a bar wearing a dress, and she wouldn't often return to her Long Island hometown during the daylight hours because her mother didn't want her to be seen by the neighbors, according to the new biography, Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar by veteran journalist and author Cynthia Carr.

"There was a kind of glass ceiling that was thicker than glass for her."

She also struggled to make ends meet for her entire short life — she died at age 29 from lymphoma in 1974.

Identifying neither as a drag queen nor a "pre-op" transsexual, Candy Darling was ahead of her time in just wanting to live as a woman. She used her striking appearance and natural charm to make connections and construct her own persona. But even in Warhol's Factory and the underground scene in Greenwich Village, there wasn't always a place for someone who didn't conform to gender norms and yearned for acceptance as a legitimate stage and film actress.

"There was a kind of glass ceiling that was thicker than glass for her," Carr says.

A History of a Lost Era

In her new book, Carr recounts a glittery life cut short and creates a fascinating portrait of an era when someone trying to forge a new identity could mingle with the Rolling Stones, Jane Fonda, Warhol and other celebrities at spots like Max's Kansas City and the Chelsea Hotel.

Candy befriended and collaborated with other non-gender-conforming figures like Holly Woodlawn (also featured in "Walk on the Wild Side") and Jackie Curtis; appeared with Tennessee Williams in his play, "Small Craft Warnings"; and was photographed by the likes of Richard Avedon and Francesco Scavullo.

"I do think of this as a cultural history of that time in New York and also early off-off Broadway, the beginning of second-wave feminism, and the beginning of the gay rights movement, and Candy's life is like the heart that's running through it," Carr says. "I think it's important to show what everyday life was like to understand her better; not only how interesting it was but how dangerous it could be."

Carr, a longtime Village Voice writer and author of the Lambda Literary Award-winning "Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz," spent 10 years meticulously researching the life of her subject.

Asked to write the book by Jeremiah Newton, a longtime confidante of Candy's, Carr had to navigate multiple obstacles. Newton had once intended to write a book about Candy and shared a cache of interview tapes and Candy's personal papers, but it was up to Carr to sort the jumble of boxes containing everything from old Christmas cards and tax forms to letters from Candy's mother and her journals.

"What really got me interested was the story of her struggle as a trans woman in Manhattan," Carr says. "She was going to fancy parties, hanging out with Warhol and being acclaimed for her beauty, and then she goes home to Massapequa and her mother says don't come home before dark and don't let anyone see you. That was a hint of what she was going through in her life. I said, I have to [write this book], without knowing it would take 10 years."

Further complicating Carr's work was that Newton hadn't taken meticulous notes and didn't always know the full names of the people he interviewed. Plus, many of Candy's friends and associates had either forgotten or mixed up key details. It was especially hard to find people who knew Candy when she was growing up, as her half-brother didn't want to participate in the book and her parents were dead.

"I was lucky to find a few people who had gone to school with her," Carr says. "I finally found the journal she kept during her teenage years. That was of critical importance since it was the beginning of her transitioning."

A Superstar Is Born

There's a star is born aspect to Candy's story, which is also the subject of a 2010 feature documentary, "Beautiful Darling." According to the book, Candy possessed a certain "it" factor, despite mostly living in poverty and having notoriously bad teeth.

"She was very friendly and outgoing," Carr says. "For one thing, she almost always needed a place to stay. She meets Jeremiah and says, how about if I stay at your house? There was always that thing going on — she needed some help. She knew tons of people, and it seems like she had a kind of charisma. It was always noticed – several people said if she crossed the street, she would stop traffic, literally."

Yet there were limits on how far her charm and talent could take her. Even Warhol, who brought Candy into his world, always considered her a drag queen.

"He really liked Candy and he did think of her as a drag queen but that she was really good at it and better than the other ones," Carr says. "He was really interested in drag from a young age. He thought she was the best example of drag that he had ever seen. I think he really liked her as a person and started taking her to fancy parties because she was very beautiful and witty, and she did not ask him for money. He did some things for her that he didn't do for other people."

As Candy became known among New York's downtown elite, she still often had to sleep on a friend's couch or bunk in a fleabag hotel, and perform sex work, just to get by.

Even at her death, her funeral was almost relegated to a derelict facility before a friend intervened and insisted it be held at Frank E. Campbell's, the Upper East Side institution that has handled memorials for Judy Garland and Rudolph Valentino, among many luminaries. Actress Julie Newmar spoke at Candy's funeral, which was attended by throngs of admirers, but her family still thought of her as "Jimmy."

Candy's story has a real retro quality. She very much tried to emulate Hollywood stars like early talking era actress Jeanne Eagels and 50s and 60s icon Kim Novak and didn't view herself as an activist.

Fame But Not All Glory

"I'd like to think if she had been able to live a little longer, she might have started to think about [the politics of her identity] differently," Carr says. "When you're very focused on surviving, that becomes the main thing — she never made that political. Who knows what would have happened with her if she lived a little longer?"

Candy's pining for her one true love also seems like something out of the "women's pictures" she loved, however, Carr doesn't believe she ever had a real, romantic relationship.

"They were all infatuations," Carr says. "She never had a real boyfriend, which is what she wanted. I think she was so guarded and kind of masked. Her real feelings didn't come out that much, except in her journals, so she was always a little bit hidden, even from good friends. If you're going to have an intimate relationship with someone, you have to let them see you in a way that she wasn't comfortable."

Ultimately, Candy Darling wasn't quite able to live on her own terms — never realizing her dream of Hollywood or Broadway success – but she came close.

"She came to be regarded as [a] very beautiful woman in Manhattan society but couldn't get anywhere in terms of her career," Carr says. "If she [had] managed to live this long, she would have had some options."