The Why and How of Sharing Your Family Story

Tips on how to do the research, organize what you find and preserve family history for future generations

Those who remember older relatives are bequeathed a sacred gift: their family story. Those memories — the legacy — become incrementally more precious after loved ones are gone.

And why does it even matter? Christina Baldwin, in her 2005 book "Storycatcher," explained, "We all need a story to stand on: a core belief that affirms who we are, which we won't relinquish no matter what."

Good or bad, it is our story. The reason to explore family history begins with us and journeys to the past. That others may find value beyond our lives is a side benefit.

As the author of three books about my family, I've learned the ropes of genealogy through trial and error. I've learned that you can uncover stories that will send shivers down your spine, as I did when learning my Virginia ancestors were enslavers in the 18th century.

"Start with yourself and tell the story from your experience. Then move back one generation at a time."

What do you want to accomplish in telling your family story? Curt Sylvester, president of the Indiana Genealogical Society, tells the beginner, "Start with yourself and tell the story from your experience. Then move back one generation at a time. At each generation, record the story of your direct ancestor, and then share about other family members. Tell about your ancestor's siblings, spouses and the children of all the siblings. In researching an ancestor's sibling, one often finds information about their direct ancestor that would have never been known without this special search of siblings." Using this method, Sylvester found that he is related to President George Washington.

Chances are good that iconic historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr., host of PBS' "Finding Your Roots," isn't showing up at your door with a fleshed-out multi-generational chart and pictures of your celebrity relatives. So, where to start? Four steps can get you organized and moving:

Do Your Research

Use your smartphone to interview older relatives while you can. I regret never interviewing my grandmother, who sparked my interest in family history. Ask open-ended questions and be nosy about what documents and relics they have. If they don't relinquish a copy, take a photo with your phone.

After exhausting family ties, visit your local library. Librarians are magicians and willing to help. Library collections may include court and land records, history and yearbooks, photographs, and vintage newspapers. Newspapers ran weddings, obituaries, property records and other clues to the past. For example, an obituary of my great aunt's death in a car accident provided further understanding of my grandmother's rocky childhood.

The Church of Latter-Day Saints also has multiple centers and a free online database to research and record your ancestors. Helpful volunteers are available at centers, such as the John Parker Library and Family Search Center at the National Underground Freedom Center in Cincinnati.

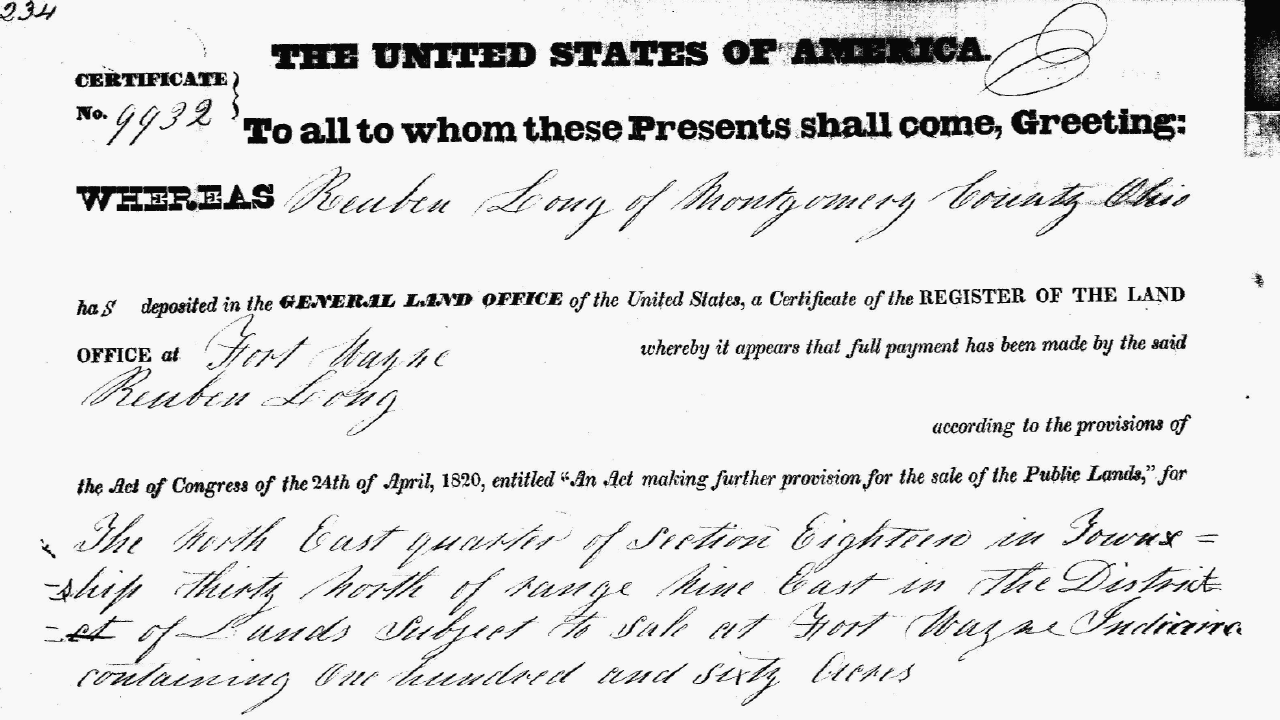

Federal government sites like the U.S. Census, military records, land patents, immigration, and the National Archives and Record Administration hold records back to the 17th century. Persons of European extraction may believe relatives came through Ellis Island, which didn't open until 1892. Further research may be needed for ports from Boston to New Orleans before that date; many genealogy sites list ship manifests with name, age and country.

Are there family members who want a land title from 1883? You can't know until you ask.

Persons with enslaved ancestors may find information through federal sites if family names are known or use sites like the Digital Library of American Slavery.

Family Tree Magazine suggests individuals descended from enslaved persons focus on living relatives and documented information since 1870.

The magazine noted, "Be especially alert when you reach the 1870 census, the first taken after slavery ended and the first to enumerate formerly enslaved people by name. Every household member is named, but relationships aren't specified. You may look at families who banded together after emancipation, leaving them stranded in hostile environments far from blood relatives. A couple or single parent may have taken in — not necessarily given birth to — the children listed in the household."

Primary source documents are the currency of research and include diaries, letters, official documents, films, speeches, manuscripts, interviews, and news stories. Many states record birth and death records, but availability depends on each state. For example, no death records existed in my state before the 1880s. Ensure you are dealing with a government site and not a third party who may charge excessively.

Genealogy is big business — read the fine print and know the fees for third-party sites. When using a browser, be aware that the first sites listed paid for that privilege and that a free site may be available.

Documentation is king. Written corroboration that accompanies a relic is known as provenance. A distant cousin owns a Civil War-era flute belonging to our mutual second great-grandfather. While we have his military records and a photograph, nothing ties the flute to him except legend.

Inventory and Organize What You Have

I'm not the most organized person; I work in piles rather than files, so I made four piles: Save, Donate, Pass On and Toss.

Save was easy — do I want my parent's wedding pictures? Yes. Do I want the 80-pound RCA Victor floor-model Victrola from 1918? No. Donate items like this to a museum or historical society. My mother gave her wedding dress to a local historical society that displays bridal dresses from different eras.

Pass It On. Are there family members who want a land title from 1883? You can't know until you ask.

Toss. In an Ikea world, our kids don't want our stuff. And there's always Goodwill, where you may be able to claim a tax deduction.

Preserve Your Collection

The Internet offers many digital preservation options that don't have fees. Choose a site like Family Search to preserve information for future generations. Proprietary sites like Ancestry, Genealogy Bank, and My Heritage charge a fee, but many can be accessed free through a library. Sites like Indiana Memory accept vintage scanned photographs for preservation; check your state historical association for what they accept.

My high school has an alumni center and accepted copies of the 1974-75 student newspapers I had kept. Scan all you can; we scanned 500 Ektachrome slides from the 1960s and put them on flash drives. If there are prominent relics, like the Victrola, take pictures, describe the item and upload pictures to a family history site.

The Presentation of Your Family's Story

I told my stories in book format. No book is necessary unless that's your inclination. Make a memory book or design scrapbook pages. Use Storyworth, a company that provides written prompts turned into printed books.

Tell your story with your unique skills, make a quilt, a painting or photographs, or author a poem. Make an heirloom cookbook and ask family members to contribute. Start a family website, blog, or Facebook group about all or specific branches of your tree.

Researching family history never ends. Something drags you back in when you think it's done. My maternal grandmother repeatedly told me stories until they were burned into my memory DNA. Her stories were clues that helped me find more information, which led to more stories.

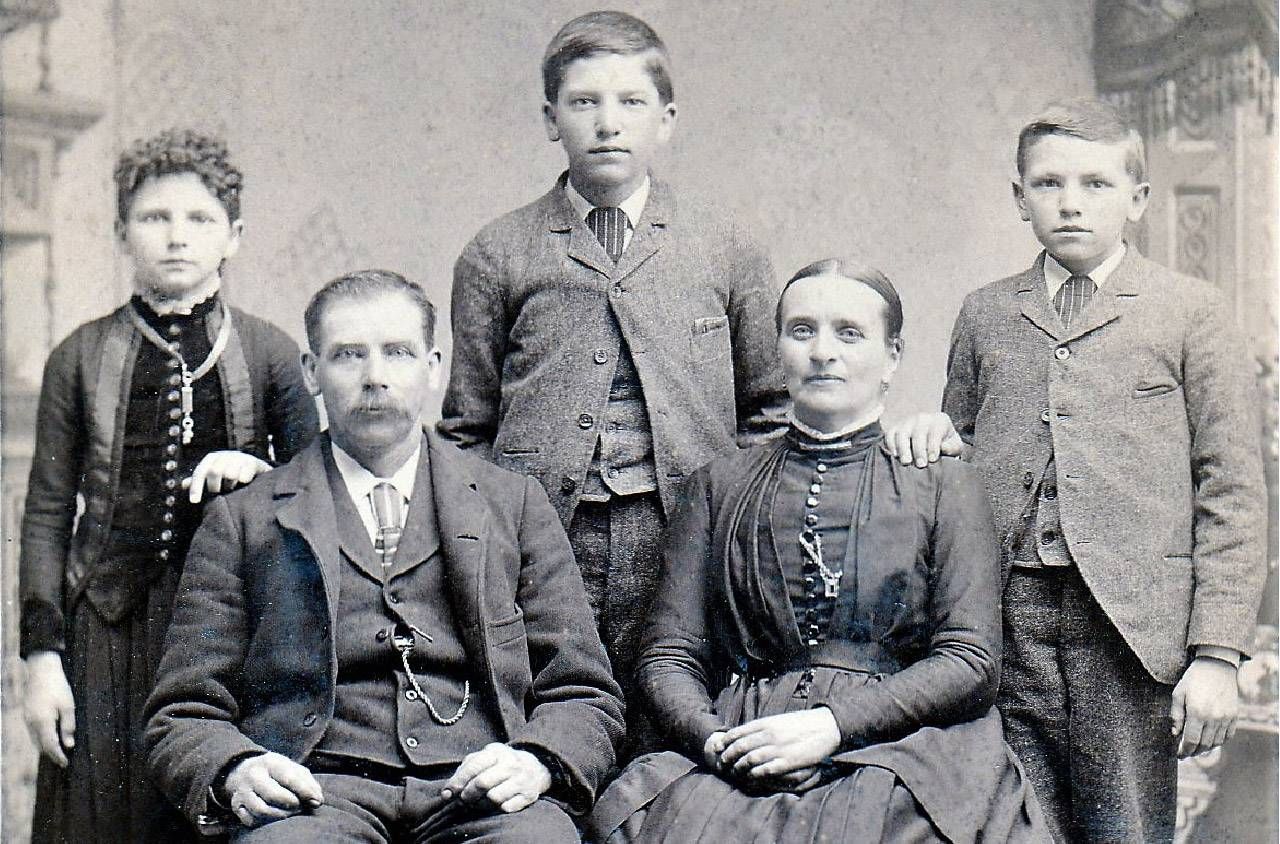

My great-great-grandfather had a brother who died in the Civil War. Union soldier Lewis Long, a member of the Mississippi Marine Brigade, caught dysentery after Vicksburg and died 300 miles from home. Too young to enlist, my ancestor, Washington Long, farmed the 160 acres his father Reuben purchased through an 1837 land patent. Because Washington did the work and cared for their mother, his siblings signed over their acreage to him after Lewis' death. The ownership changed directly affected every generation to my own until the farm was sold in 2010. I don't know why my grandmother failed to tell me something so important.

Genealogy is a fulfilling hobby, and the Internet offers numerous places to dig up family secrets. Your grandchildren may now only feign interest, but likely when they are grandparents, they will be grateful for the legacy.