Why I Didn't Say 'Thank You for Your Service' on Veterans Day

A 'one size fits all' expression about a part of one's life that was emotionally and physically difficult may miss the mark for many veterans, including my brothers

My dad was a proud World War II veteran. Two of my brothers also served in the armed forces, as well as most of my uncles, many cousins and one of my nieces. I guess I am — in some small way —from a "military family."

But you won't hear me saying, "Thank you for your service" — on Veterans Day or any other day.

My reasons are complicated. Mostly they have to do with one brother's severe PTSD and how he truly hated hearing that phrase. But I'm also aware that many veterans — perhaps a majority — are simply uncomfortable with being thanked.

A Range of Reactions

I need look no further than my own family to see the breadth of veteran opinions about being told "thank you for your service" (TYFYS).

I never asked my father how he felt about this phrase but I didn't have to. Dad, who died in 2008, always wore a poppy on Veterans Day, flew the flag on all of the patriotic holidays, and often sported a "U.S.S. New Jersey" hat. He would have smiled and said, "you're welcome."

Tim passed away in 2022 but to say he felt uncomfortable hearing TYFYS is a gross understatement. He detested it.

It only took one generation for that warm feeling to evaporate.

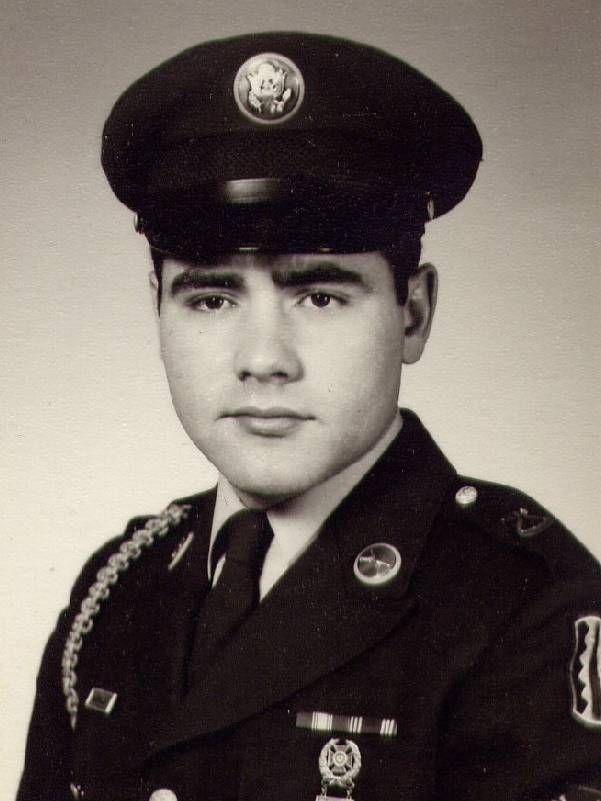

My brother Tim was barely 18 when he was shipped off to Vietnam in 1966. His experiences there left him psychologically scarred for life. Tim passed away in 2022 but to say he felt uncomfortable hearing TYFYS is a gross understatement. He detested it.

Fast forward one more generation and the pendulum has swung back again. My niece Tamiko served in the Air Force for nine years. "When someone says that to me," she says, "I am humbled and honored."

So there's my father and my niece on one end of the spectrum and my brother Tim on the other. In the middle are people like my brother Pat who served during the Vietnam War but was not stationed there. "It's awkward," he says of the phrase. "I never know quite what to say."

His feelings may be the norm.

A 2021 survey conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of Cohen Veterans Network (CVN), a nonprofit serving veterans' mental health needs, found that 58% of veterans polled felt uncomfortable being thanked. (That number was up nine points from 2019.)

What exactly is it about this innocuous (on its face) expression that rankles so many? The reasons are as diverse as the veterans themselves.

TYFYS Can Be Triggering

For veterans with PTSD, TYFYS can be triggering. This is my foremost personal reason for not using the phrase. As noted above, it's based upon my experience with my brother Tim.

Tim returned from Vietnam in 1968. He was 19 years old. He never talked much about his experiences there but it's clear that he never really left the war behind.

There wasn't much support for veterans returning from Vietnam; PTSD did not become a medical diagnosis until 1980. Tim wasn't tested until the 90s. He was in his 50s when he was finally awarded disability based on his PTSD.

Throughout his adult life, my brother struggled with substance abuse, mental health issues and homelessness. Tim's severe PTSD (he was informed that his PTSD score was "off the charts") meant that he was unpredictable and explosive. (I have to add here that he was, simultaneously and paradoxically, the kindest, most generous individual I've ever met.)

There wasn't much support for veterans returning from Vietnam; PTSD did not become a medical diagnosis until 1980.

I was with him a few times when he was told "Thank you for your service." I can still recall the look of rage and pain on his face, equal parts furious and heartbreaking.

A logical conclusion would be that Vietnam veterans — drafted to fight in an unpopular war and receiving a chilly reception when they returned — would be the group most likely to struggle with PTSD and thus least appreciative of hearing TYFYS.

But that may not be a safe assumption. Indeed, research indicates that post-9/11 vets have a greater lifetime risk of developing PTSD than Vietnam veterans.

The bottom line for me is that I have no idea if the veteran I'm meeting has PTSD and might be triggered by hearing this phrase.

TYFYS Can Feel 'Loaded'

For many other veterans, TYFYS is just short of triggering. It is simply too loaded. The reasons behind this are numerous and difficult to entangle for many vets.

The history of TYFYS itself grates on some veterans. It's only been in the past two decades that the phrase has become nearly ubiquitous. "I started hearing it a lot after the war in Iraq started," says my brother Pat. "It felt like enforced patriotism. I think you can be patriotic and still question your government."

"I'm sure that part of my discomfort is that I was drafted when I was 19 years old. I didn't have a choice. Hell, I couldn't even vote."

But this isn't a simple question of an individual's politics. Research shows that "feelings of warmth towards veterans are high across political ideology."

It's a conundrum. My brother has deep respect for those who've served. But TYFYS feels performative to him. Like slapping a "Support Our Troops" bumper sticker on your car and never giving it another thought.

"I'm sure that part of my discomfort is that I was drafted when I was 19 years old. I didn't have a choice. Hell, I couldn't even vote," says Pat. He knew the war was about stopping the spread of communism — a vague goal with a faceless enemy. "It was a very different experience for World War II vets. They came home to parades."

TYFYS Is Too 'One Size Fits All'

The backgrounds, lives and views of America's 18 million veterans are incredibly diverse. Their military experiences differ wildly as well — from being drafted to enlisting, from serving stateside to being posted in a combat zone, from a stint as an officer to that of a "grunt." Their reactions to TYFYS are equally varied.

Jacob Thomas, an Air Force veteran and communications director for Common Defense, a community of progressive veterans, says most veterans have "complex feelings" about their service. "Everyone who served will have their own unique experience with their military service so [responses] can be different for each."

People are, in a nutshell, complicated. A "one size fits all" expression about a part of one's life that was, very likely, emotionally and physically exhausting (at minimum) may miss the mark for a lot of veterans.

Ellen Moore, author of "Grateful Nation: Student Veterans and the Rise of the Military-Friendly Campus," spent years researching the lives of veterans on college campuses. When she asked veterans how they felt about TYFYS, the responses ranged from "appreciation to active dislike."

She added, "Many said that the phrase, coming from strangers who knew nothing about them besides their military status, seemed like a platitude; it seemed like something civilians thought they were supposed to say."

Ultimately Moore concludes, TYFYS may perpetuate an uncomplicated view of military service and of war generally. It can inhibit deeper discussions that might be beneficial for the veteran.

Beyond 'Thank You for Your Service'

For those who, like me, would like to show their support yet have reservations about saying TYFYS, there are options.

You could use an alternate greeting like "thank you for your sacrifice" or some variation of that phrase. But those possibilities may be only marginally less triggering or loaded than TYFYS.

"Instead of saying something, consider asking something. Show genuine curiosity with questions like, 'What was your job while serving?'"

"Instead of saying something, consider asking something," urges Anthony Hassan, president of CVN. "Show genuine curiosity with questions like, 'What was your job while serving?'" (You'll find many more conversation starter ideas online.)

Actions, of course, speak louder than words. Veterans are at greater risk than the general population for substance abuse, mental illness, suicide and homelessness. You can show your appreciation by supporting one of the myriad organizations working on these issues.

Some veterans encourage well-wishers to become informed and involved in the politics that surround military decisions.

Your way of showing your support will be as unique as you and your circumstances. I try to honor my brother Tim's sacrifice (and that of so many others) by volunteering at a local homeless shelter.

I also support candidates working to ensure a world with fewer wars. And to guarantee that, if we do send young people off to fight for us, we take care of them when they return.