'Not a Single Casserole' — What It's Like to Be Widowed by COVID-19

Spouses and families are left to grieve without sympathy or support

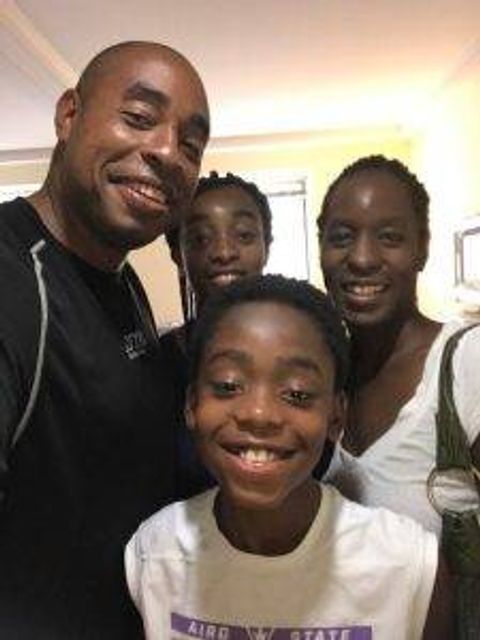

In her last FaceTime conversation with her husband, Simone Andrews begged him to keep fighting.

“They were going to intubate him and after that he would be sedated and he wouldn’t be able to talk,” said Andrews. “He was afraid. I said, 'Please, please, don’t give up. Keep working hard.'”

Andrews’ husband Levester Thompson, known as LT, had begun feeling lethargic as the family prepared to shelter-in-place in their Staten Island, N.Y. home in mid-March.

Four days later, after his fever spiked and he experienced a seizure, LT was hospitalized.

“He didn’t have the symptoms. He wasn’t coughing and we weren’t thinking COVID, but that was his diagnosis,” Andrews said. “I thought he would come out of it; he was just forty-six and healthy, he worked out every day, no pre-existing conditions.”

On April 6, LT died on a ventilator, never regaining consciousness. Because of visiting restrictions put in place at the start of the pandemic, Andrews and their two children saw him only through an iPad during the 19 days he was hospitalized.

“We didn’t know he was at the end and we didn’t say goodbye,” Andrews said. “And then we went into our grief bubble. My parents and in-laws couldn't come and be with us. It was too risky to see anyone. It’s like we were marooned.”

Our Commitment to Covering the Coronavirus

We are committed to reliable reporting on the risks of the coronavirus and steps you can take to benefit you, your loved ones and others in your community. Read Next Avenue's Coronavirus Coverage.

'One of the Many'

On the day LT died from the coronavirus, so did 876 other New Yorkers. The sheer scale of the number of those lost to COVID-19 is staggering.

Each one of those casualties is attached to a family unable to access cultural rituals that accompany the end of life. Many funerals or memorial services have been cancelled or delayed. Those that can be staged are often conducted via an online platform, with guests attending virtually, unable to hug or put a sympathetic arm around the bereaved.

"Grief naturally isolates you, but many of these widowed people have not touched anyone for months."

The coronavirus is robbing a new generation of widows and widowers not only of their life partners, but also of their ability to access community support networks as they mourn in isolation.

“This is unprecedented. It’s compared to 9/11 in terms of the intensity, but it’s more than that. These newly widowed people become one of the many. And their person is a piece of the larger tragedy — they are a number,” said Michele Neff Hernandez, founder and executive director of Soaring Spirits International.

Hernandez founded the California-based nonprofit after she was widowed at 35 and wanted to find a way to meet others who had also lost their partners. Since 2009, Soaring Spirits has put on more than two dozen Camp Widow events across North America to help bereaved spouses though education and by introducing them to widowed peers.

Soaring Spirits is now reaching out to COVID-19 widows and widowers with specifically designed information and Zoom meetings that replace face-to-face interventions.

“They have a lot in common,” Hernandez said. “Grief naturally isolates you, but many of these widowed people have not touched anyone for months. That lack of affection and connection as this crisis has stretched on and on keeps them in that cauldron of pain.”

In the support groups, facilitators stress the importance of self-care and finding ways to reach out, even when they’re staying home alone.

“Our work is to connect them to each other and remind them of their resilience,” Hernandez added. “We suggest therapy as an option and have workshops on how to find a therapist.”

Traumatic Grief

Support groups and other resources designed specifically for COVID-19 widows and widowers are beginning to emerge.

Based in Manhattan, the pandemic’s epicenter when LT died, psychotherapist Danielle Jonas is providing online therapy for people who have lost a spouse or romantic partner to the coronavirus.

“In the U.S., we have decided what a good death looks like. The person is surrounded by their loved ones, they’re comfortable. Maybe there are songs or prayer,” said Jonas.

None of the partners of her newly-widowed clients were afforded anything resembling that good death.

"It's imperative to understand that for many of these widows and widowers, this is not just grief. This is trauma."

“When the spouse can’t be present at the end their loved one’s life, they’re haunted by the idea that their person didn’t remember why they were alone. They ask themselves, did they feel neglected or unloved at the end?," said Jonas. “These survivors feel guilt: They should have gotten (their spouse) to the hospital sooner, they should have taken their symptoms more seriously. They may wonder and worry if they brought the virus home to their loved one.”

The loss experienced by those widowed in the pandemic is also complicated by its unanticipated nature, according to Laura Takacs, clinical director for grief services at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle.

“It’s imperative to understand that for many of these widows and widowers, this is not just grief. This is trauma,” said Takacs.

She considers COVID-19 widows and widowers to be “sudden traumatic death survivors.” That designation is typically assigned to those who lose a spouse in a sudden, shocking or violent way and are tortured by their thoughts of their loved one’s last moments.

“These survivors can’t get images of their loved one’s death out of their head. They can’t sleep, their thoughts get caught in a loop. They think they’re going crazy,” Takacs said. “I expect we will see this with COVID losses, where they ‘see’ their loved on a ventilator or imagine them suffering in a crowded hospital ward.”

Using a method called restorative retelling, Takacs gives sudden traumatic death survivors coping skills for when they wake up in a cold sweat, and educates them to normalize their experience.

“I tell them, these are the symptoms I would expect; other spouses describe similar feelings. You’re not alone,” she said. “When they hear that, there are often tears of relief. Then we can go to work.”

Isolated in Grief

There’s a fragment of a song stuck in Darlene Thoreson’s head.

“I keep thinking of that line, ‘You picked a fine time to leave me,’” said Thoreson, 71. “This has been so horrible. I can’t tell you how lonely I am.”

Thoreson and her husband Eric, 77, had moved to a senior living building in suburban Milwaukee on March 1. They were still unpacking when Eric began feeling ill. He attributed his body aches and breathing difficulties to his persistent asthma, but on the night of March 28, his condition quickly deteriorated and he collapsed and died in their living room.

While Eric’s symptoms were consistent with COVID-19, a postmortem test was inconclusive. Darlene tested negative for the virus but was quarantined under a tight lockdown with the assumption that she’d been exposed.

“I couldn't leave and no one could come in. They slid my mail under the door and wouldn't take the rent check from me because Eric made it out and had touched it,” she said. “Everyone was so leery of me.”

"I've experienced death in my family before. Everyone swarms around you and takes care of you. There was none of that."

Unable to lean on her two daughters, her friends or the pastor at her church, Thoreson was isolated in an apartment that didn’t feel like home.

“I’ve experienced death in my family before. Everyone swarms around you and takes care of you. There was none of that. Not a single casserole,” she said. “We’re not meant to grieve alone.”

Late-in-Life Loss

Although the average age of people dying from the coronavirus has begun to drop, statistics compiled by the Centers for Disease Control this spring found that Americans 65 and older account for eight out of ten of the U.S. deaths from the disease.

That means a disproportionate number of the newly-widowed due to COVID-19 are those who’ve celebrated silver, gold or even diamond anniversaries.

“Their pain is deep. They’ve lost their life’s companion, their source of security, perhaps their protector when they were feeling vulnerable, and this is happening in the middle of a crisis like we’ve never experienced,” said Steve Sweatt, clinical director at Community Grief Support in Birmingham, Ala.

Sweatt has facilitated support groups for older widowed spouses in the past and has seen their grief patronized. He wonders if that will become a more frequent response in the coronavirus era, when some pundits and policymakers have suggested that older people should sacrifice themselves for the sake of the economy.

“Our culture is too often dismissive of late-in-life loss. The cliched response is, 'They should be thankful for their many years together.' But that’s callous in the extreme,” Sweatt said. “This undermines and disenfranchises their bereavement.”

An Intentional Life

Two weeks after LT died, Simone Andrews returned to her job, working from home as a therapist. Some of the clients she now sees remotely have been touched by the coronavirus, too.

“It’s been almost a blessing to have this job when I’m going through this loss. It gives me something within my control,” she said.

Andrews finds herself distracted, though, by her unexpected status as a widow and by the cascade of existential questions it raises.

“Why am I here and he’s not? Why wasn’t it both of us? It’s such a crap shoot, such a game of chance,” she said. “But I’m here and I want to live in the most intentional way possible. I am not going to waste this life.”

Andrews has resumed running, found a therapist and is conscientious about both her physical and mental health, motivated to “get my body in its best shape” to increase her odds of being present for her children.

“In my doctoral training, they stressed that a good clinician is constantly evolving. This has deepened my understanding of loss. What I’m learning will inform my work and my life moving forward,” she said. “And I will move forward.”