Is an Aging Population Hurting the U.S. Economy?

Some analysts think so. Here's why they're wrong.

U.S. economic growth has been underwhelming for some time, averaging around 2% these days. In recent months, economic commentators have intensified their search for the underlying reason why the economy can’t kick into higher gear. They’ve landed on this highly disputable explanation: Too many old people.

That’s right. The dreaded “silver tsunami.” The economic core of the fear-based narrative is that — with more Americans expected to be 65 and older than 18 and younger by 2035 — there’ll be too few young workers to financially support too many dependent elders. Consequently, these analysts say, the U.S. economy is condemned to a permanent state of stagnant growth at best, and possibly much worse.

Sound and Fury of Doomsayers

Here are two examples that appeared in The New York Times: Ruchar Sharma, chief global strategist at Morgan Stanley Investment Management, wrote: “Demographics are usually the main driver of economic growth, so it is basically inevitable that these countries will now grow at a much slower pace.” And the Times’ economics writer Eduardo Porter observed that “the aging of the American population is carving an unexpectedly broad path of destruction across the economy… Many of our most intractable economic ills can be traced to some degree to this ineluctable fact: America is getting old.”

Can't we shed this hidebound way of framing aging?

The economic pessimism about aging isn’t limited to the U.S.

A recent United Nations report saying that global aging will weigh on economic performance around the world noted it would increase the “fiscal pressures that many countries will face in the coming decades as they seek to build and maintain public systems of health care, pensions and social protection for older persons.”

This message of worry resonated during the June meeting in Japan of leaders from the G20 nations, too, where aging was on the priority list for discussion for the first time. And not in a good way.

Winter of Our Discontent?

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda worried there that an aging population could pose “serious challenges” for central banks, according to Reuters. Japanese Finance Minister Taro Aso warned his colleagues that they must act now on the issue of aging to take “effective measures against it.” (At least that’s better than when he asked older people “to hurry up and die” several years ago.)

Really? Can’t we shed this hidebound way of framing aging?

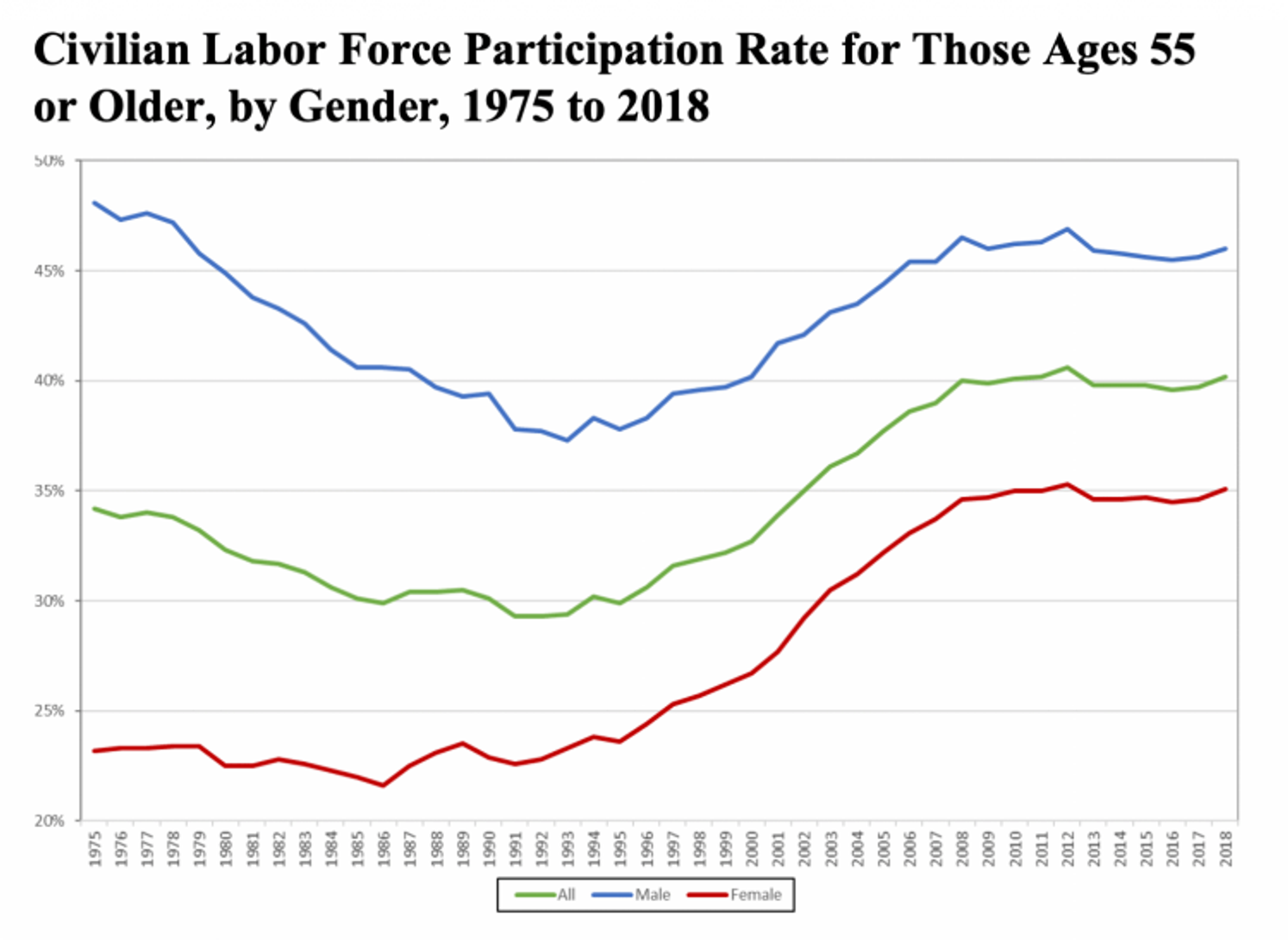

The dire-demographics-of-aging school routinely ignores a major social and economic paradigm shift among people in the second half of life: They’re working longer. The trend toward continuing to earn a paycheck later in life is well documented, yet the dramatic shift in behavior remains vastly underappreciated.

Economic Numbers Showing Some Analysts Protest Too Much

Consider this:

- Around 90% of the increase in employment in the U.S. since 1998 has come from higher employment of workers 55 and older, calculates Andrew Scott, economist at the London School of Business.

- The labor force participation rate for people age 65 to 69 has risen from roughly 28% in 1998 to 38% in 2019 for men and from 18% to about 30% for women.

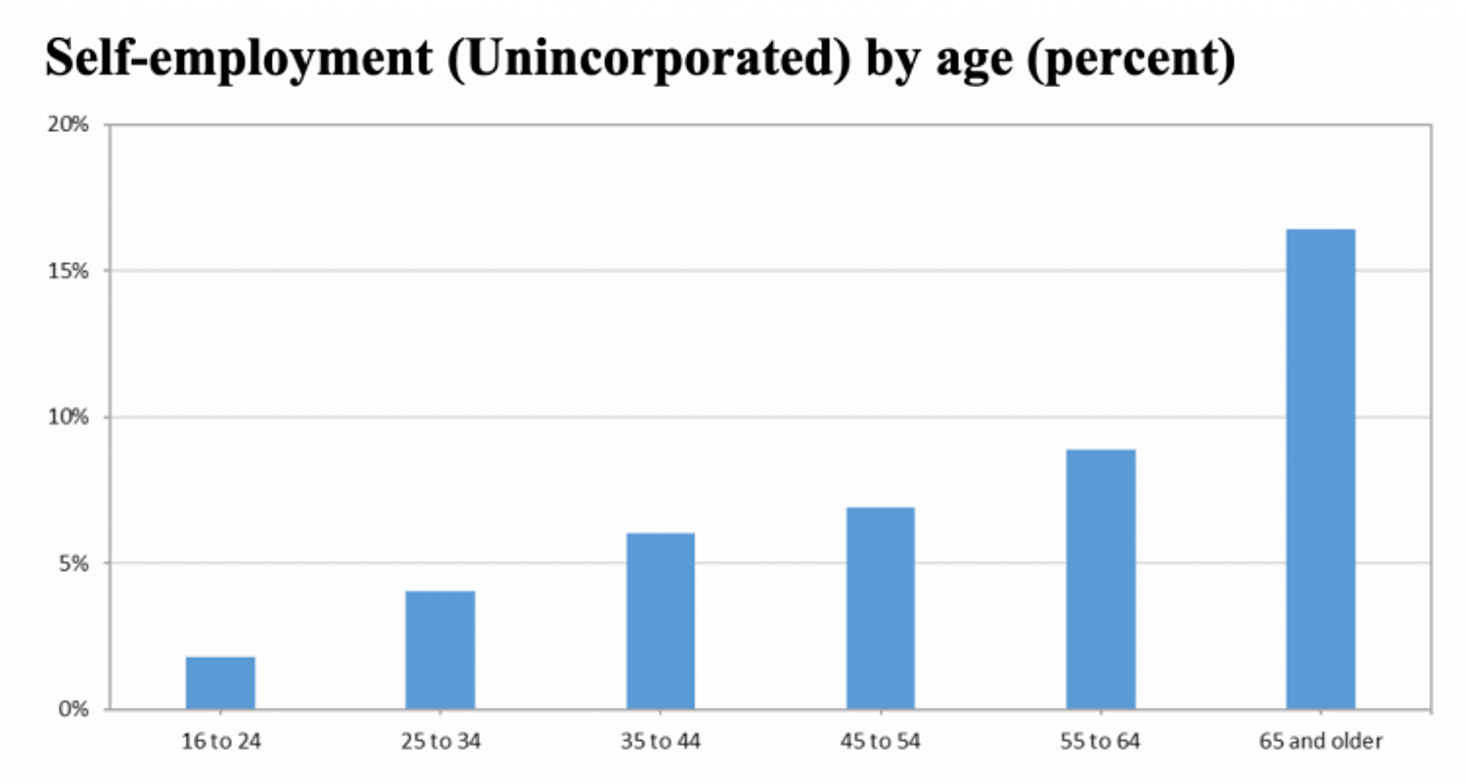

- Adults between ages 55 and 64 made up 26% of new entrepreneurs in 2017, according to the Kauffman Foundation. That’s a significant increase over the 19% percent figure in 2007.

Scholars in a variety of disciplines have created a research-rich story highlighting the enormous opportunities for America opening up with aging populations. Chief reasons: Older adults are healthier, better educated and more productive than previous generations.

“Thanks to their ingenuity and economic demand, the boomers have the potential to open up possibilities for older adults across the economic spectrum, across nations, and even far into the future,” wrote Joseph Coughlin, director of the MIT Age Lab and author of The Longevity Economy: Unlocking the World’s Fastest Growing, Most Misunderstood Market.

Older workers are productive workers, concluded a series of studies demonstrating the benefits of experience, including several from the Munich Center for the Economics of Aging. Their conclusions remind me of Ronald Reagan’s quip during the 1984 presidential campaign when his ability to do the job was challenged because he was 75. Reagan promised not “to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.”

Why Past Isn't Prologue

It’s true, as a new MIT Technology Review article said, that Harvard economist Nicole Maestas and her colleagues have estimated that a 10% increase in the 60+ U.S. population between 1980 and 2010 reduced per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth by 5.5%. But, as the article also noted, Maestas says the past is no guarantee of the future since people are working longer these days. “Are we all getting less productive, and we’re stuck with that? Not necessarily,” Maestas said.

Instead of hand-wringing about aging, the exciting challenge is to create incentives and institutions that welcome experienced employees in the workplace and entrepreneurs in the second half of life. Given the opportunity to continue using their skills and knowledge, experienced workers can be a powerful force for rejuvenating businesses and nonprofits and, yes, boosting U.S. economic growth.

“Older people stand out for their combination of experience, interest, and ability to fill skill gaps. They are a human capital resource that is ready to contribute to companies, younger colleagues, and a vibrant economic future," wrote Paul Irving and co-authors in the Milken Institute’s Center for the Future of Aging publication, Silver to Gold: The Business of Aging.

Here’s the thing. Despite the striking employment gains since the early 1990s, American society and employers have only just begun to reevaluate the promise of experienced workers. The supply of those people is much larger than their opportunities. The barriers of age discrimination and ageism are real.

We Ripe and Ripe

Yet the U.S. economy would gain if managements put out the welcome mat.

PwC, the giant consulting firm, created a Golden Age Index to quantify how countries in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are harnessing the power of older workers. New Zealand has the second highest rate of employment of workers 55+ in the OECD. The U.S. is down at No. 9.

The American economy would expand by over $815 billion if the U.S. increased its employment of the 55-to-64-year age group to New Zealand’s level, according to PwC.

“I would suggest that the ability to spot, mobilize and deploy older workers is the next biggest source of competitive advantage in the U.S. companies,” wrote Tyler Cowen, economist at George Mason University. “The sober reality is that many companies should retool their methods to fit better with the experience and sound judgment found so often in older workers.”

No, aging and decline aren’t synonymous. Just read the smart report from the Global Coalition on Aging and the Health and Global Policy Institute, “The Impact of Innovation Across Technology, Health, Care and Urban Design for Super-Ageing Societies.”

It looked at measures that would build more vibrant communities around the world. Two of the researchers’ insightful recommendations: encouraging age-friendly communities to become “test beds” for new products, technologies and social interventions and promoting education and training initiatives for older people, especially as caregivers.

To further increase the labor force participation rate of experienced workers (as well as workers of all ages), health and retirement systems could be redesigned to support a mobile workforce and to encourage older workers to stay in the job market longer. Employers could offer more late-career training and phased retirement programs that let people keep working in their 60s and beyond, just not 40-hour workweeks. And colleges could embrace education and training initiatives for workers in their 50s, 60s, 70s and older who want to boost their skills.

Framing matters when it comes to the U.S. economy. Stop playing the blame game with “old folks.” Instead of seeing growing older through the lens of inevitable decline and frailty, think about the opportunities an aging population could open in America’s workplace and startup culture.