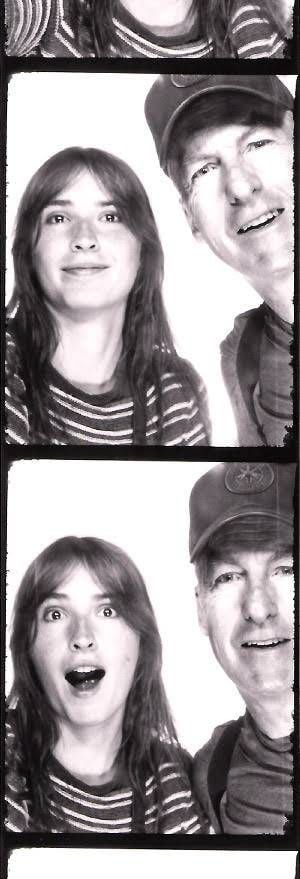

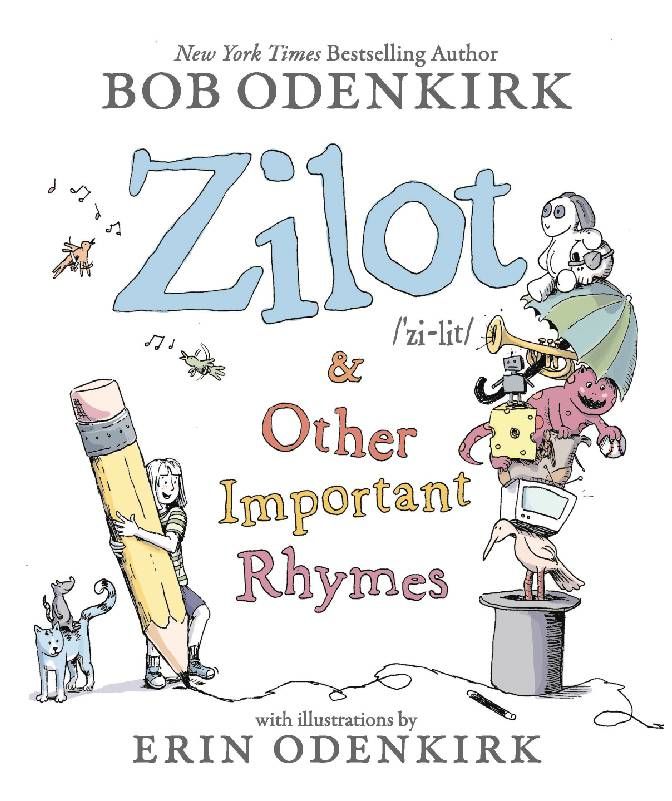

Bob and Erin Odenkirk on Family, Art and the Joy of Creating ‘Poetic Nonsense’

The 'Better Call Saul' star and his daughter discuss their new book, 'Zilot & Other Important Rhymes,' which was decades in the making

For more than 35 years, Bob Odenkirk has gained recognition both as an actor ("Breaking Bad," "Better Call Saul," Greta Gerwig's "Little Women") and a sketch comedy writer ("Mr. Show with Bob and David"). His 2022 memoir, "Comedy Comedy Comedy Drama," was a New York Times bestseller, and he's won two Primetime Emmy Awards for Outstanding Writing for a Variety or Music Program — one for "The Ben Stiller Show" and one for "Saturday Night Live," where, as a staff writer, he wrote Chris Farley's famous "van down by the river" sketch.

And yet, he says these accomplishments pale in comparison to his latest project — a book of poems he created with his children.

The book, "Zilot & Other Important Rhymes," began as a family project. Odenkirk wanted his children, Nate and Erin, to know that real people created their favorite books and that they, too, could someday write and illustrate books of their own. They began crafting silly poems and creating new words — zilot (pronounced /zi-lit/) was Nate's made-up name for a blanket fort — compiling the pieces into a homemade book titled "Old Time Rhymes."

"I called it 'Old Time Rhymes' as a joke. Obviously, they weren't old at all; we had just written them."

"I called it 'Old Time Rhymes' as a joke," Bob tells Next Avenue. "Obviously, they weren't old at all; we had just written them. I thought the kids [would] smile and laugh at the idea that you're calling it old; it's not remotely old."

Decades later, during the early days of the COVID pandemic, Nate and Erin were attending college classes from the Odenkirk family home. Erin, now an illustrator, began creating art to accompany the old poems, and in time, the project morphed into a fully-fledged children's book. Though the content is promoted as "poetic nonsense," the poems are quite impactful, as they encourage readers to nurture their creativity, celebrate their individuality and embrace their mistakes.

And Bob shares that audiobook lovers are in for a treat. "There's going to be an audiobook of this," he says. "It's read by me, Emo Philips, Maria Bamford, Ron Funches and Samuel Robert Epstein, and it's accompanied by music by Eban Schletter, who did all the music for 'Mr. Show.' I'm really proud of it. I just picture kids who are lucky enough to have the audiobook with the music getting to turn the page and hear it read."

Over a recent Zoom call, Bob and Erin Odenkirk talked about the original concept for the book, the importance of art for art's sake and what they want readers to get from the poems.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Next Avenue: This is such a fun book. Can you share the story of how the poems originally came about?

Bob Odenkirk: Once upon a time, I was good friends with a guy named Ben Stiller. We were young men making our way in comedy, and I recognized that because Ben grew up in show business, he had more confidence and [his] sense of making stuff was legitimate. He didn't question that. There's a big overcome for people who didn't grow up around the arts, and I wanted my kids to have a feeling that they could be writers and artists. I thought the way to do that is when you read books to the kids at night, put them down and write a poem, just like what you just read. And then they'll see that they can do some version of what is in these professionally made books that they'd just been reading over and over.

So once or twice a week, in our reading time, we would write a poem, and I would really let the kids participate. I wouldn't just tell them what it should be or change all their words. I would let them write the first line, or I would write two lines and they would write two lines. I would write them down the way the kid just said them; I wouldn't change them. So what we ended up with were a lot of really nonsensical poems. I mean, really absurd. Because a kid who's four, five, six thinks that rhyming means reusing the same word again. But I wouldn't correct them; I would just write it down. I also knew that a few of those poems were good — there was a good idea there.

So I kept them as a memento for the kids. I thought I would maybe rewrite them when I was a grandparent. But then COVID hit, and these two kids, Nate and Erin, were in college, doing their classes in their bedrooms, and having a lot of free time. And Erin was an artist. I said, "Let's rewrite those poems, and Erin, you do drawings." And that's where this book came from.

A Book Decades in the Making

What was it like when the finished copy arrived in the mail, and you saw your names on this book of poems that you'd created all those years ago?

Erin Odenkirk: It's crazy. It feels like it just appeared out of nowhere. I mean, we started it when I was a little kid, and then we started reworking it about four years ago now. And between the time that we submitted the last drawing and the time we got that in the mail was another six months, maybe. And so to just have a finished book show up at your doorstep with your name on it, it's wild! I still have to sometimes sit and remember, "You did the work. And that book that was on your shelf when you were six years old — there's stuff from that in here." That's crazy!

So this book was actually decades in the making.

Bob: It was. And, in its way, more work than [my] memoir because I really wanted the memoir to feel like me talking, which can be sloppy and repetitive at times and kind of casual. That's what I wanted it to be, and I think it comes across that way. When you're writing poems, if you do it right, you should be caring about each word and being very economical. On the other hand, in editing it and rewriting it, I didn't want to lose the fact that I wrote it with a kid. So if it felt too manicured, I think it might lose the feeling that a kid helped write this.

Erin, I looked over your portfolio on your website, and there's so much variety in your work. How did you decide on the look for this book? Who were your influences?

Erin: Thank you for looking! That's a great question. I did have specific inspirations. I will hearken to Shel Silverstein, who obviously is one of the poetry kings, but I think we're different from him in going for a younger audience — simpler art, a little less grotesque, a little sweeter. I also looked at illustrators that I grew up with — Dr. Seuss, Mark Alan Stamaty. A lot of ink-line drawings, simple. The first drafts of the art for this book were a little darker and had more depth, and maybe were more adult. We had to rein that in a little bit because it just didn't feel right.

The style we ended up with is the style that I draw in my sketchbook. It's my shorthand. I think the art that fills the rest of my portfolio are pieces that I've spent hours on that need to feel like they are professional, [whereas] this style that the book ended up in is one that is meant to complement the words.

Many of the poems touch upon the idea of art for art's sake and not worrying about what others think. Was that something that you're intentionally trying to impart through this work?

Bob and Erin, simultaneously: Absolutely.

"My family did encourage me to hold on to the feeling of uninhibitedness and exploration that kids are born with, and a lot of the art for art's sake poetry in our book is trying to inspire a connection with that feeling."

Bob: Yeah. There's a few themes. Wordplay is one of them. You know, invent your own word, like zilot. Have fun with words and turn them inside out and invent little words like the made-up tree names in [the poem] 'That Time of Year.' Have fun with language! Don't be afraid of it. Goof around with it. And don't be afraid to try and fail, because failure is part of growing and doing anything. So yeah, those are some pretty strong themes.

Erin: And art for art's sake is a great way to put one of them. Art for art's sake should be something you carry throughout your whole life, but I think it's super important when you're a child. It's a great way to express yourself, express your feelings, mark your growth, explore, try things. I definitely grew up feeling very self-critical, and the older I got the worse it got. I think my family did encourage me to hold on to the feeling of uninhibitedness and exploration that kids are born with, and a lot of the art for art's sake poetry in our book is trying to inspire a connection with that feeling.

Having Fun With the Process

Bob, in your memoir, you referred to yourself as "pushy and quite sure of myself" and a "control freak" when it came to your work. What did this experience of writing with your kids teach you about letting go and having fun with the writing process?

Bob: [Laughs] Ah, you suggest that it taught me anything. It's always a negotiation. I think the best things that I've done in my career have been a collaboration — that goes [for] 'Mr. Show with Bob and David,' collaborating with David [Cross] on that show, and everybody I collaborated with on 'Better Call Saul.' I didn't write it, but everything about that show was a deep collaboration. I'd say the same is true here. Erin's influence and what worked and didn't work — we tried to complement them properly.

Our editors, Farrin Jacobs and Mary-Kate Gaudet, were very into our work. We read these poems aloud, talked about each word. We went through the whole book probably four times. So I guess it taught me the lesson I need to learn again and again: to interact [with] and listen to other people. I feel great about where we landed with it.

Erin, with this being your first children's book, how was it for you to get feedback from outsiders? As an artist I imagine you're used to doing a lot on your own.

Erin: Yeah, it's helpful at times and it's frustrating at times. I think the experience of having my dad in the house as I was drawing it was both of those things at once. There's many times I felt stuck and having my writing partner be able to walk 10 paces, open the door and give me a suggestion was super helpful and fun. But of course, I was also 19 and he was my dad and sometimes that was annoying. [Laughs] I just wanted to do the bad draft alone and then come back two weeks later with a good draft. And also, yeah, I'd never done anything like this before. It was nerve-wracking sending stuff in every time, wondering, "Is anyone going to take me seriously?" But they did. And each time they did I felt more confident and more sure of myself. The having done it each time made it easier to do it again.

Thoughts on Banned Books

We are in the midst of rampant book bans, and children's picture books are not exempt from that. What do you say to those who are challenging books and attempting to keep librarians from doing their job?

Bob: I think banning books is one of the scariest things you can start messing with. There's no question there should be an adult section of any movie, film, music [to provide] a sense of what audience they're intended for. But to a great extent, that shakes out without anybody needing any government organization [to] assist. You should allow the ideas and words and stories and inventions of writers and artists to live in the world and let people acclimate towards them organically and learn from them and be challenged by them.

I think the fears that people have are just crazy. What are you afraid of? If you've ever shown a movie to kids, and there's an adult moment, you'll see that they just don't get it. They don't see it, they don't hear it, it doesn't land. And the reason is because they're kids, and they're protected by their innocence. You don't have to cover their ears; it just goes right past them. That's my experience. Depriving people of other thoughts and influences and voices is not going to help them invent themselves in the best, healthiest way.

"Some kids are in difficult scenarios, and they have tension or anxiety in their life, and just to tell them that there's better days ahead is also a running theme [in the book]."

What advice would you give to parents who would love to instill creativity in their children but think, "I'm not a writer, I don't know how to draw. I can't create with my kids"?

Bob: Again, when I let the kids write with me, we worked together. I would let the kid write the first two lines of the poem, and I would write it down exactly the way they wrote it. I wouldn't change it right away. And they very often wrote things that were extremely nonsensical. But I would write it down, and I wouldn't correct them. And at some point, I'd say, 'There you go, we did it. We're done.' And I put it in our little booklet, and gave them the sense that, 'I wrote a poem today!' Wasn't a very good one. [Laughs] But so what? Everything everyone does starts terrible. Nobody sits down and writes a masterpiece. You start with rough, raw stuff, and then you make your way.

Erin: When you're that young, to not put pressure on having anything amazing is great. I taught an eight-year-old art classes, and the biggest thing I learned was to come in with direction and a goal so they felt like they were being led and they could jump aboard safely. And then secretly, what you know is that at a certain point, they're leaving the train and you shouldn't correct them. You should just let it go where it goes because that's the best part.

What do you want readers to get from this book?

Bob: I want people to laugh and smile, but there's some deeper feelings I want to share. Obviously, an encouragement to write and play with language and not be afraid of language, but just feel like you can have fun with it. But [also], each effort you make starts with mistakes and trying again, having an attitude of, 'Oh, well. Let's carry on. Let's do it again.' [An example is] the poem 'The Great Day,' where the kid makes all kinds of mistakes, but in the end, he's got a smile on his face. 'Who could have done all that? Only me! I'm pretty special.' But the other thing is a poem like 'Later.' Some kids are in difficult scenarios, and they have tension or anxiety in their life, and just to tell them that there's better days ahead is also a running theme [in the book]. Hang in there, let time do its work.

Erin: I really hope that kids enjoy the art, that it makes them smile and laugh, and that even if they're too young to read the words themselves, they can enjoy the visual jokes and the beauty of it. Whether it's being read aloud to them, or they've just encountered it by themselves, that they can get lost in it a little.

Read More