Frank Bruni Sees Illumination in the Fading Light

In his new book, ‘The Beauty of Dusk,’ the journalist navigates compromised vision and stares at possible blindness

Over the past five years, journalist Frank Bruni has come to see the beauty of dusk, what he calls "those first real inklings that the day isn't forever and the light inexorably fades."

It's a metaphor for Bruni's journey of self-discovery that began one Saturday morning in the fall of 2017 when he awoke to find words on his computer screen that "occasionally shimmied" underneath a "dappled fog." When the fog didn't lift and the shimmying didn't stop, Bruni tried cleaning his glasses, then the computer screen, then showering with his face to the spray.

Perhaps it was a "phlegmy residue" on his eye or simply "the four generous glasses of wine" he had with dinner the night before.

But there was no panic, no alarm, not even a question put to Tom, his romantic partner at the time and a doctor no less, with whom he would go to a dinner party that evening. Bruni wouldn't even mention the odd and reduced vision out of his right eye until the following day.

"This is bad, isn't it?" Bruni asked the doctor. She nodded and said, "This is bad."

That's when Tom urged him to see his ophthalmologist, who opened his office on a Sunday, examined Bruni and then recommended he see a specialist, a neuro-ophthalmologist.

She, in turn, gave Bruni a "field exam" that measures your blind spots and compromised field of vision. Two hours after he arrived, she shared her diagnosis that would subsequently be confirmed: Bruni had suffered a kind of stroke that caused a sudden drop in blood pressure to the optic nerve behind his right eye, ravaging the nerve. There was no treatment.

And by the way, she advised, "This could happen to your other eye."

"Could or will?" Bruni asked.

"About a forty percent chance," the doctor said, but that chance shrank significantly if the left eye stayed healthy for the next two years. (Other doctors put the chances as low as 15%.)

"This is bad, isn't it?" Bruni asked the doctor. She nodded and said, "This is bad." And after a few seconds of silence, said, "I'm sorry. I have nothing to offer you."

With compromised vision in his right eye, Bruni has also had to contemplate a similar fate for his left eye that would effectively render him blind.

Given his way with words, I'll let Bruni read a 13-minute excerpt from the beginning of his just released memoir: "The Beauty of Dusk: On Vision Lost and Found" — how he "went to bed seeing the world one way and woke up seeing it another."

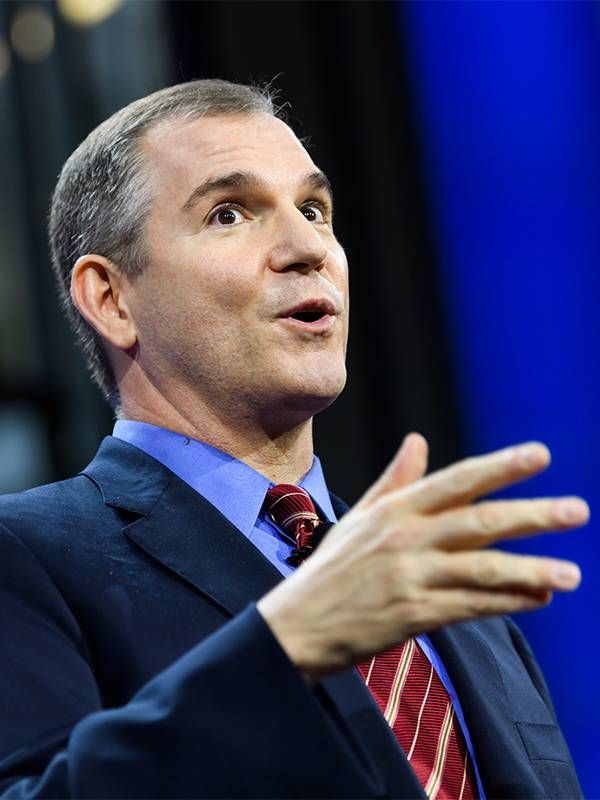

After more than a quarter century with the New York Times as an opinion columnist, restaurant critic, Rome bureau chief and White House correspondent, Bruni is now a professor of the Practice of Journalism and Public Policy at Duke University and writes a weekly newsletter for the New York Times.

He spoke this week with Next Avenue:

Next Avenue: It's been five years since the beginning of your eye odyssey. You're 57, among the youngest of Baby Boomers, born in the fall of '64. You've described boomers as 'overconfident' and 'defiant' weekend warriors who trade one fitness craze for another, who have a trove of pills and who don't make allowances for the inevitability of aging and affliction. Does this help explain why you brushed off your impaired vision in the first day or so?

Frank Bruni: That's exactly why. I was of the mindset that sure, there are going to be physical challenges coming down the road. There were going to be ailments, but in large measure until I got very old, modern medicine would just come along and fix things.

I just assumed that whatever was happening was some transient thing that would work itself out. And I assumed that to the extent that it might not be, the minute I did get to a doctor, I would be told here's the pill you're going to take. Maybe here's the eye calisthenics you're going to do. I just assumed there'd be a remedy.

What was it like when you first heard your neuro-ophthalmologist say, "This is bad. I have nothing to offer you?" There is no treatment.

It was surreal. I said to myself on an intellectual level, okay, I'm going to have to really do some serious thinking and regrouping. Within a matter of days, I had raised my contribution to disability insurance to the maximum, something I never envisioned myself doing.

To that end, I rather quickly started making myself listen to audiobooks because I thought this may be the only kind of reading I'm left with in time, and so I'd better damn well learn how to do it now. But on the emotional and psychological level, it was just surreal, because you sit around alone or with your friends wondering about things that may happen to you. What if I have a heart attack? What if I get cancer? I don't know anyone who says, What if I go blind?

Finding the New Normal

I'd imagine if anyone heard their doctor say, 'This is bad. I have nothing to offer you,' it would make the hair stand up on the back of the neck. So you had two choices: curl up in the fetal position, or go into journalist's mode to see if science had any possible treatments in the pipeline.

Yeah, I totally did. It was tempting to curl up into the fetal position. It was tempting to be melodramatic and self-pitying about it. And I never thought of myself as a particularly strong or resilient person. But I think one of the lessons I learned is that we are all much stronger and more resilient than we realize.

"If you are alive, you are at the mercy of fate to a large degree and you have no idea what's coming down the road."

And so if I wanted the easiest path to my new normal, I had to start blazing that trail right away. Any delay was going to just make it that much harder. So I interviewed prominent doctors about it as a way of gathering material, but also as a way of educating myself. I enrolled myself in the one existing, possibly promising clinical trial of a treatment, which turned out to be in my age range and the diagnostic criteria to qualify for.

I think doing all of that was important to me in a way that could be important for anybody battling any unforeseen affliction. It gave me some sense of control and agency. It made me not a completely passive person, but somebody who was exercising the power and control I did have.

I've heard you say that once doctors put a name to your condition — NAION (non-arteric anterior ischemic optic neuropathy) — you were at the mercy of fate, which you call the very definition of vulnerability.

I was told it might make a difference if I stayed really well hydrated, especially before I went to sleep. And so I do, and I get up to go to the bathroom a lot during the night, and that is my new normal. That's not just about aging, that is about my water intake late in the day.

I was also told that it might be a good idea — no one was really sure — to avoid super high altitudes. So I do not have a trip to Nepal planned and probably will never take one. I was told this [condition] is just a roulette wheel in a casino. And that is a very strange feeling.

I was told I had a sword hanging over me that had these particular initials: N-A-I-O-N. All of us have swords hanging over us. But we don't know what the shape or nature of the swords are. If you are alive, you are at the mercy of fate to a large degree and you have no idea what's coming down the road.

Most of Our Struggles are Not Visible

You and I are both in the stroke survivors club. Mine was more than twenty years ago and I fully recovered with some residual numbness. And from your book, I know you came to believe after your stroke that we would all do better if we appreciated what others are going through and virtually everyone is going through something.

None of us is the same remotely, the same on the inside as the outside. Most of the profound struggles we go through — medical as well as psychological — are not visible to the people around us. The scars we carry with us, the anxieties that are the legacy of stuff we've been through, that stuff is usually not visible. And I think it would be a much different and saner world if we all remember that.

The metaphor I came up with for that in the book is if we all walked around wearing sandwich boards, just listing the main things we're struggling with at that moment, we would all make much more realistic assessments of our own welfare and our own kind of state of mind in relation to everybody else's. I think we'd all be much less prone to self-pity, and I think we'd all find empathy more quickly than we do.

So if I wrote on my sandwich board "stroke survivor, numbness on my left side, came in handy for COVID vaccination shots in my left arm," what would you write on yours?

Mine would be pretty simple at this point. I would say "Eyesight compromised. Could go blind." That's the central uncertainty and struggle of my life at the moment. But that sandwich board might have said something different twenty years ago, and it'll probably be longer or the main item on it will be different ten years from now. It's not what's on the sandwich board that I find so compelling on mine or others. It's the fact that there is something to put on everybody's sandwich board.

The Love of a Dog Named Regan

In addition to both of us having survived stroke, we're both dog people and one of my strongest memories after returning home from the hospital twenty-odd years ago was taking long walks with Buster, our wheaten terrier who proved very therapeutic to my recovery. You wrote how Regan, your border collie, "countered and blunted the panic and pain" following your stroke. And how she took you "outside of yourself." What did you mean by that?

I think it is logical when something happens to you, like what happened to me or what happened to you, because you have to pay a lot of attention to your own welfare and you have to gather information, make a lot of decisions. You can become extremely self-consumed in a good self-care way, but you can also become so consumed in a self-pitying way. If you were lavishing care and energy on something outside yourself, it necessarily puts the cap on the amount of worry you can accord yourself.

In that sense, Regan took me outside myself in a very, very helpful way. But also, you know, I mean, she brought strains of joy and love into my life. I love her. And that was like this kind of blast and burst of positive energy that was a nice counter to the negative energy of having a very scary medical affliction to worry about.

Are you in a better frame of mind than you thought you'd be five years ago when you first learned of the damaged optic nerve?

Yes, I'm in a much better frame of mind than I thought I'd be. If you had said to me, 'How good are you going to be at navigating this situation, at weathering the setback?' no matter how I appear in the world, I would have told you I'm a fairly frightened, pessimistic, weak person inside. And this is going to be a disaster. That's what I would have predicted. And it hasn't been a disaster. It has been a challenge at times. It has been an education, but it has also been an illumination.

One of my dear friends is a woman in New York named Louise Grunwald — she's the widow of Henry Grunwald, editor of Time magazine. He virtually lost his eyesight and wrote his own book "Twilight: Losing Sight, Gaining Insight." And that's a really great way of describing what can happen in a situation like mine or in a situation like yours or a situation of any kind. Not having necessarily to do with vision and ocular stuff, you gain insight as a function of the challenge you've been given. I am really grateful for that dimension of this.

You mined a lot of wisdom in your book from some very accomplished blind people. There was former federal judge David Tatel who told you "Starfish can regrow limbs. But that's nothing compared to what human beings can do."

And Juan José Gómez Camacho, Mexico's former permanent representative to the United Nations, suggested that blindness had forced him to be patient. "I never saw it as a burden. I saw it as a characteristic ... you might wish to be taller or thinner. But you are what you are." Five years on, are you at a point where you can say your vision impairment is not so much a burden, but a characteristic?

Most days, yes. Not every day, and that's OK. It's not a clean, chartable graph line from fear to courage, from anxiety to utter composure. It's a jagged line and there are days when I do not see my compromised, diminished vision just as a characteristic. And there are days when I do, and there are days when I don't even think about it, which is kind of remarkable. But I think the general movement in a jagged fashion is towards a kind of acceptance that Juan José talks about. I think that's one of the gifts of time.