How Religious Groups and Cults Shaped American Eating

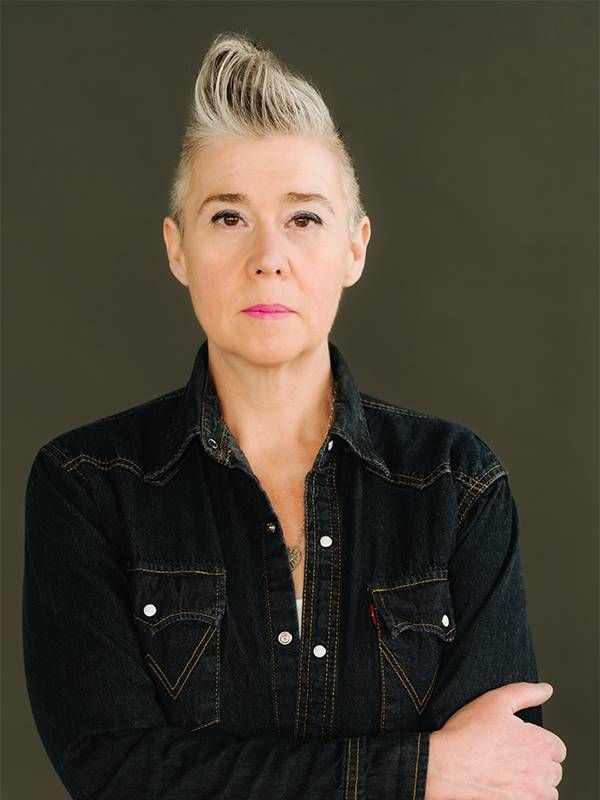

Christina Ward, Milwaukee-based food expert and historian, discusses her latest book and offers insight on regional and personal holiday food traditions

Frog Eye Salad isn't nearly as savory as it sounds. Nor does it contain peepers extracted from the jumpy amphibian, either. It's a coconut and pineapple-laden sweet take on chilled pasta salad.

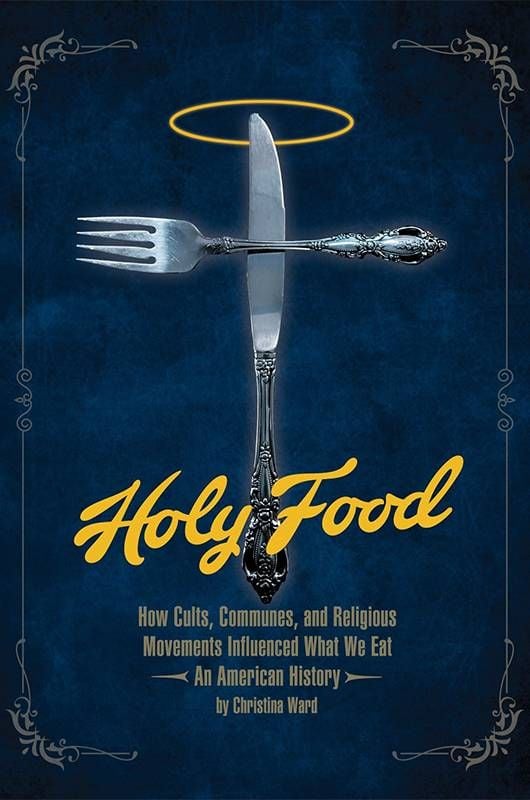

Author Christina Ward's latest book, "Holy Food: How Cults, Communes, and Religious Movements Influenced What We Eat — An American History," provides the recipe and breaks down the more profound history of the creamy dish.

Where the recipes are like dessert — a rich and indulgent complement to the main dish – the historical facts this book serves up is a hearty feast.

"I'm definitely one of those weird 'why?' people. I always want to know why."

As it turns out, the Frog Eye Salad hails from the Church of the Latter-Day Saints (LDS), which dates back to the early 1800s. Most of the Mormon community follows the LDS tenets, and some of their practices — predominately polygamy — have recently netted them a place in mainstream media in TV programs like "Sister Wives."

In Ward's book, she amply informs readers about various religious groups and their beliefs, highlighting their respective food evolutions. With the Mormons, for example, their oral tradition of sharing recipes established very basic iterations of everyday dishes; eventually, missionaries brought back cooking traits from the regions they visited on their treks to spread their gospel.

Fascinations With Food

The way food and spiritual quests intersect is only one of Ward's food-related fascinations.

An author, editor, and VP of Feral House Publishing, Ward has penned other food books including "American Advertising Cookbooks: How Corporations Taught Us to Love Bananas, Spam, and Jell-O;" "Preservation: The Art and Science of Canning, Fermentation and Dehydration;" and the recent "Happy Days: The Official Cookbook." The latter is about the iconic TV show, a perfect task for a food expert from Milwaukee, where the show was set.

Ward is a go-to expert on food for platforms from news stations to blogs; she even got to ride around in the Wienermobile with the former "Top Chef" host Padma Lakshmi on her breakout TV show, "Taste the Nation." Ward does what you do when you've got a ton of eats or a platter of information before you: she digs in.

Ward's 'Why'

From an early age, an interest in food and an all-consuming curiosity has been a part of Ward's makeup. "I'm definitely one of those weird 'why?' people," she says. "I always want to know why. Growing up in a mixed household — my dad was kind of agnostic, and my mom was Catholic — I went to Catholic schools, and that gave me an early awareness of the different ways people do things. And our church was an Italian and Irish Catholic church, so it was very food-oriented. I made an early connection between religion and food."

She also cooked at an early age for siblings — not uncommon for young Gen-Xers – and spent summers helping on her grandparents' farm; she says those experiences helped build her food-knowledge foundation.

Media played its part, too, in an aspect of her book. "Growing up in the 70s and 80s, there was a cult awareness — all of those after school specials that showed how cults would snatch you off the sidewalk, which led to realizing there was a lot more to that topic, but that was my evolution of interest (in cults)," Ward says. "That interest has been there since childhood. Then, later, putting together some other connections, like Kellogg's and Little Debbie's roots in the Seventh Day Adventist Church. All of those things made me want to dig through it all and unpack it."

Compiling it all, telling one big story, added excitement to Ward's interest. "It's how my brain works. If I were talking to you in person, I'd corner you and say, 'Wait, let me tell you about this weird thing,' so this is my way of telling everyone, and they can read it on their timeline," she says. "I also collect cookbooks, and I was aware some of the groups (in the book) had been publishing cookbooks. So, I wanted to tell that bigger story — that was really the impetus."

Another component that often threads through these movements and groups is using food and diet as a means of control, which the book thoroughly examines.

"If you look at some of the dogma of these groups, some of it is very radical — they would like to impose their dogma and belief systems on everyone because they think it's best," Ward notes. "That's the challenge with any religiously informed diet morality — the arrogance that comes with it – that their way of thinking is better than everybody else's and that they're doing you a favor by imposing it on you."

"In a city like Milwaukee ... you can safely guess that we have an incredibly dynamic food culture."

"Holy Food" took Ward five years of "active research and writing." She says that one of the most interesting parts of the deep dive was finding a through-line of connectivity.

"Not just of the food, of the religions, of the new religious movements and how connected they are to each other. Not just modern connections: some things link back to the 1700s. How connected all the beliefs are and how all the actual people are was a revelation and surprise to me," she explains.

Folklore and Holiday Food Magic in Milwaukee

Ward was born in Milwaukee in the late 1960s and talks about the city with a familiarity that travels well beyond being a resident. She attributes the mix of choice eats to its diverse human blend.

"I've said this to people, food writers, and even Padma Lakshmi, but I firmly believe we become 'American' through our stomachs," Ward says. "In a city like Milwaukee, with a long history of European settlement and immigration that welcomes migrants and refugees, you can safely guess that we have an incredibly dynamic food culture."

When the winter holidays roll around, Krampusnacht on St. Nicholas Eve night (Dec. 5) is a big deal. Courtesy of movies and an inherent intrigue, the folklore figure Krampus has been growing a vast U.S. following, especially over the last decade. For Milwaukee folks, it's been prevalent for well over 100 years.

"Krampus and St. Nick came to Milwaukee with the thousands of Germans seeking refuge from persecution during the 1848 German Confederation Crisis. St. Nicholas Day is celebrated on December 6, and Krampusnacht on St. Nicholas Eve night of December 5," Ward says.

"In the legend, St. Nick brings treats to good children on the morning of his day, while the American version of Santa makes him do the work of keeping a 'naughty or nice' list. St. Nick outsources the finding (and punishing) of the 'naughty' on the evening of December 5 to a more sinister Krampus," Ward explains. "Rough stuff, but in Milwaukee, we love Krampus and St. Nick because no one is ever so naughty to be snatched by Krampus!"

On the morning of December 6, kids of all ages will find a stocking or shoe filled with treats. And in Milwaukee, there are rules. "According to the Milwaukee St. Nicholas tradition, the stocking must contain the following items: an orange, a handful of walnuts, pecans and hazelnuts, pieces of chocolate and a small present," Ward adds. "The celebration of St. Nick has been severed from both the religious and ethnic roots to become a people's holiday enjoyed all."

Carrying on Traditions, Honoring Memories

Ward, who grew up enjoying Christmas Eve by gathering with family and friends to share a meal and open presents, recalls that though many holiday dishes exemplify the holiday's religious roots, her dad eschewed those foods in favor of his favorite — pizza.

"Dad's best friend from childhood was the second-generation owner of Maria's Pizza. Dad and Ronnie were close, and their 'gang' hung out at the pizza parlor," Ward says. In 1967, her dad even donned a Santa suit for the place.

As it happens, the friends found less time to hang out as they got older, but they found a way to connect.

"Dad would toss the pizzas in the oven, and we kids were in awe that while every other kid we knew had to sit still and eat their vegetables, we got to eat Maria's."

"On December 23, after his shift at the factory ended, my dad would go to Maria's and spend the waning hours visiting Ronnie, reminiscing and catching up. Then, in the pre-dawn morning, Ronnie would make two or three 'par-bake' pizzas for Dad to take home," Ward says. "In addition to the other plans of the day, Dad would toss the pizzas in the oven, and we kids were in awe that while every other kid we knew had to sit still and eat their vegetables, we got to eat Maria's."

Ward's father passed away in 1999. "He was 54 years old, the same age I am now. As I went to the house to bring order to the chaos that follows an unexpected and tragic death, I noticed the pizzas were in the fridge. We were no longer children, but we would always be his kids."

And for Ward's family, the tradition continued. "For 24 years after Dad's death, we have made the trip to Maria's Pizza on December 23 to pick up the par-bakes," she says.

While Maria's Pizza just closed after 65 years, Ward's family pizza tradition continues, growing to include new people and accommodate new dietary restrictions.

'Holy Food' Recipe:

Hog Farm Granola Breakfast (Road Hog Crispies)

Recipe note: Hog Farm Granola was famously served at Woodstock in August 1969 to the nearly half-million hungry attendees. The recipe can be scaled up to serve a larger-than-expected crowd.

Ingredients:

½ cup millet

½ cup cracked wheat

½ cup buckwheat groats

½ cup wheat germ

½ cup sunflower seeds (without shells)

¼ cup sesame seeds

2 Tbsp. cornmeal

2 cups raw (or rolled) oats

1 cup rye flakes

1 cup dried fruits and/or nuts (Use your favorites or whatever you have on hand. This recipe is very forgiving. You can add either ½ cup each of dried fruit and nuts OR 1 cup of each.)

3 Tbsp. soybean oil (can substitute canola or vegetable oil)

1 cup honey

Steps:

1. Preheat oven to 250°F.

2. Over medium heat, boil the millet in a double boiler for 30 minutes. Stir occasionally to prevent sticking.

3. In a large bowl, mix all the dry ingredients. Add in the cooked millet and mix thoroughly.

4. Over low heat, cook while mixing the soybean oil and honey together until small bubbles appear. Remove from heat and set aside.

5. Spread the cereal in a parchment-lined baking pan. Pour the honey-soybean oil syrup over the grain mix. Toast in oven until lightly browned, approximately 30 minutes. Stir once or twice to ensure even browning. Remove from oven and cool.

To serve: Pour into bowl and eat plain or with milk.

Store leftovers in refrigerator in a covered container.

Vegetarian. Can be made vegan if honey is substituted with maple or sorghum syrup. Makes 10 to 20 servings, depending on serving size.