A Poet's Commemoration of Juneteenth

How North Carolina poet laureate Jaki Shelton Green is marking the day

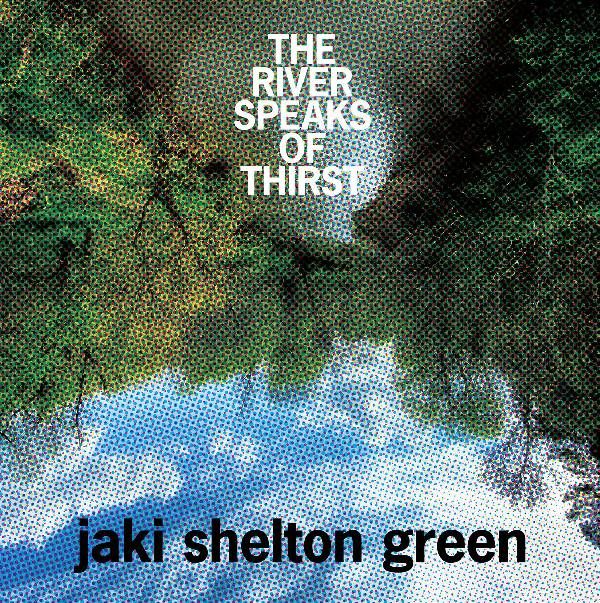

For Jaki Shelton Green, June 19 is a day layered with meaning. And this year, on the day she turns 67, the first African American poet laureate of North Carolina will mark the occasion with a new album called "The River Speaks of Thirst." With 10 previously unpublished poems, the record is a combination of spoken word and musical pieces, and features guest performers including Grammy-nominated jazz singer Nnenna Freelon.

The album is purposefully being released on Juneteenth, a day of observance in 47 states marking the day in 1865 when Gordon Granger, a Union general, delivered orders freeing the slaves in Texas. Also called Freedom Day and Jubilee Day, it was Texas which first declared Juneteenth a state holiday, in 1980.

In the wake of the killing of George Floyd by a policeman in Minneapolis and the subsequent unrest affecting the nation and the world, Green's poetry, addressing topics including slavery, lynchings and police shootings, is particularly timely.

I recently spoke to Green (whom I first interviewed in 2019 for a story about poetry for Next Avenue) about Juneteenth, "The River Speaks of Thirst" and her most memorable experience since being named poet laureate of North Carolina.

This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

Next Avenue: Tell us why Juneteenth is important to you, culturally, but also personally.

Jaki Shelton Green: It's been a prolific observation for me for many years. June nineteenth is my birthday. And in 2018, June nineteenth was the day I received a phone call from Governor Roy Cooper telling me I was appointed the first African American poet laureate of North Carolina.

People are calling for a spiritual emancipation.

The first time I heard of Juneteenth as an observation was in 1980. After Texas, a number of states were lobbying to have it declared a state holiday. In the late 1980s, Juneteenth became like our Fourth of July. Many African Americans have family reunions that day. Our family would get together for a big picnic; some years we would have thirty or forty people, and we wouldn't just go to our party, but other ones in the neighborhood as well. This will be our first year without a party, because of the pandemic.

Every year for Juneteenth, I make a special summer salad called black caviar salad. I love to cook and I wanted to make something with some of the foods that people were eating at the time of the Emancipation, and I found this recipe. It has black-eyed peas, red, green and yellow peppers, scallions, balsamic vinegar; the longer it sits in the refrigerator, the better it gets.

How do you think Juneteenth will be different in the U.S. this year?

Saying the words, 'Happy Emancipation Day,' which I always do each year, means a whole lot more. People are calling for a spiritual emancipation. We are looking for the day when we are all fully committed to a world without racism.

Juneteenth is Black Liberation Day. I hope everyone will hold that space on June nineteenth, step into a space of joy. Think about our collective call for justice right now.

People don't have to drive to attend rallies. Look at your own community. Are you paying attention to the public schools? Are you attending city council meetings?

'The River Speaks of Thirst' is your debut album. What was the process of recording an album like for you?

For years, people at readings would ask me if I had a CD. I would always say, 'Yeah, one day I'll do that.' (laughs) Then I met Phil Venable and Alec Ferrell, who are record producers, and they said to me, 'It's time. And if you want to do it, we've got you.'

I told them [recording an album] wasn't my comfort zone. I was comfortable reading, but I didn't have a clue how to do this. They told me, 'All you have to do is stand in front of the microphone and do it.'

We recorded it in Alec's living room. It was such a wonderful, nurturing space to be in. His cat, Mr. Clovis, would walk in and out. Telephones would ring. The whole experience was fun and quirky.

When I was first thinking about the album, I knew I didn't want it to just be my voice; I wanted others to read my work, too. The title song, which is the last one on the album, is a call and response. I'm reading the poem, and my friend, Nnenna Freelon, is singing the words.

In my mind, I always heard my poem 'Litany for the Dispossesse' as a rap/spoken word piece, but I would never do it at readings because that's not the way I read. An amazing poet, Shirlette Ammons, does it so wonderfully on the record. And CJ Suitt, a young African American man who is the first poet laureate of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, reads 'No Poetry,' which is another response to the disenfranchisement of Black freedom.

The poem 'Oh My Brother' is timeless, but especially meaningful right now. What is the story behind this poem?

Several years ago, I was contacted by a woman from New York who was putting together a project called the Poetry of Lamentations to mark the deaths of all the Black men and women who were victims of police shootings.

I was assigned to write about the next person to be killed within twenty-four or forty-eight hours. The idea of that took my breath away. Within thirty hours, I received a link to a news report of the shooting of an unidentified African American man in Michigan. That's all I had. No name. No anything. The poem came out of that. [After the killing of George Floyd], Alec said, 'This (poem) has to go out into the world today,' and he composed the video.

You have been the poet laureate of North Carolina for two years. What has been the most memorable experience so far?

It happened in February, 2019. In North Carolina and Virginia, there is a restaurant chain called Biscuitville. I got an email from the marketing department of Biscuitville congratulating me on being named the first African American poet laureate of North Carolina. Every year, during Black History Month, they put out a bookmark featuring a celebrated African American. They said they wanted to put my photo and bio on one side and Nina Simone on the other side. I thought, 'Okay, that sounds good.' The woman I corresponded with said the people chosen for the bookmarks 'were usually dead,' but that I was 'very much alive and had very much made history.'

I said, 'This is what standing up looks like. You just saw me walking my talk.'

She asked me if I would consider doing a poetry reading at the Biscuitville in Greensboro. That surprised me, but I've always said that art and the humanities should be in universal places, art should be taken out to the people. So I said, 'sure.'

My husband and I drove there on a Monday morning, and at 7:50, the parking lot was full. There were four TV trucks. When I walked in, the workers in their white uniforms were standing in line to greet me, like a receiving line. The women workers, all African American, were crying. The manager said, 'We are so honored to have you in our store.' The chef told me he'd make me whatever I wanted. People were standing up and cheering.

After that event, I got another call from Biscuitville, asking if I would do it again the next Monday. There were even more people, and they brought their friends and neighbors.

During that reading, four men came through the door wearing MAGA caps. They sat down, and were all looking at the bookmarks. One of them kept looking at me, then looking back at the bookmark.

At the end of the reading, the four of them walked up to me. One guy says, 'Is this you? This is so cool.'

I said, 'Yes. I'm just a little old country girl.' He said, 'Just like us.' And I said, 'Yes, just like us.'

Another one of the guys wanted to get extra bookmarks to take to his grandchild's school for Black History Month. He said, 'I just love it when good things happen to ordinary people like us.' And I repeated that same line back to him.

One of them asked if we could take a photo together because he said his wife wouldn't believe he had met the poet laureate. I said 'Okay.' But was I hesitant for them to take a picture with me? I was.

They took off their caps and put them on the bench behind us.

As they were leaving, one of the guys said to me, 'I am so honored to meet you. You keep making us proud.'

There were four young African American men at the reading and they came up to me right away. One of them asked me why I would talk to those men.

I said, 'You saw them. They approached me. They were very warm and sweet. Why would my response to them be any different?'

I said, 'I am their poet laureate also.' I said, 'This is what standing up looks like. You just saw me walking my talk. You have to be a bridge for people to cross. This is how I am showing up in my space.'

This is the story that stands out for me.