8 Policy Changes to Let Older Workers Work Longer

More employment income would help boomers who haven't saved enough

Most government policy proposals addressing Americans’ financial insecurity about retirement focus on boosting retirement savings. Tweaking 401(k) rules, creating mandatory universal retirement savings plans, that sort of thing. But there’s another approach bubbling up among retirement scholars: increasing incentives that would encourage men and women in their 50s and 60s to work longer.

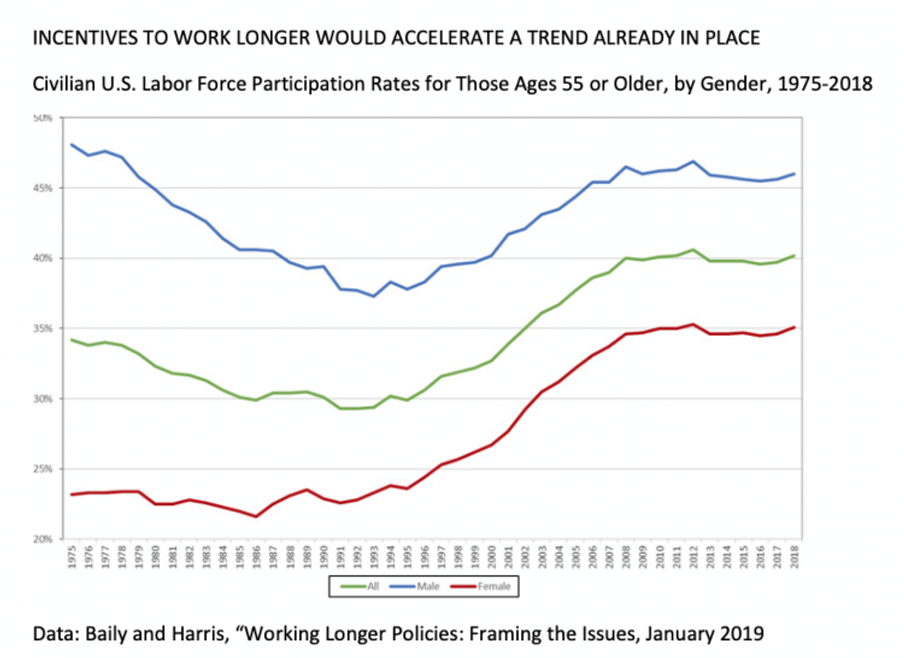

It’s true that the labor force participation rate among workers age 55 and older has been on the rise. For example, 19.9 percent of people 65 to 69 worked in 1987 and last year, 33.1 percent did. As the Trump administration's Economic Report of the President, released yesterday, said: "In 2018, more than 35 percent of the adult population was over age 55 — with 19 percent over age 65."

“Americans are responding to the changes in the retirement landscape by working longer,” wrote economists Martin Neil Bailey and Benjamin H. Harris in the recent Brookings Institution report, Working Longer Policies: Framing the Issues. But, they added, “policymakers should aim to remove obstacles to those who want to work longer and reduce work disincentives.”

How Working Longer Pays Off for Workers (and Their Employers)

Working more years, whether through full-time jobs, gig economy self-employment, entrepreneurship or encore careers, pays off in numerous ways.

Not only do workers have more income they can save for retirement, they have more years to sock cash into tax-deferred retirement plans and, if they’re lucky, more years when their employers match some of their savings. What’s more, working longer makes it easier to delay filing for Social Security benefits, which has the added effect of increasing them when you start claiming. Social Security benefits grow 8 percent a year for each year between age 66 and 70 that you postpone taking them.

All in all, the extra years of work reduce the number of years you’ll need to live off savings.

And here’s a bonus: research strongly supports the idea that working longer improves mental, physical and social health.

At a retirement security conference earlier this year, sponsored by Brookings and the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University, smarties including Baily and Harris presented their latest policy prescriptions and research for helping people work longer. These added to other thoughtful ones making the rounds.

8 Ideas to Help Older Workers Work Longer

Below are a few of the most intriguing ideas to boost Americans’ ability to work longer, if they’re healthy enough to do so. Some are incredibly persuasive. And all are ones Congress could implement.

Lower the cost of experienced workers to employers and increase these workers’ take-home pay. Economists John Shoven and Robert Clark advocate for three changes to Social Security and Medicare that could do it.

First, they say, eliminate the “earnings test” for all Social Security recipients between age 62 and Full Retirement Age (FRA) of 66 and six months. (Full Retirement Age will stretch to 67 in 2022.) The earnings test is a government-induced disincentive to staying employed.

In 2019, people who have filed for Social Security see their benefits “withheld” at a rate of $1 for every $2 of employment earnings above $17,640 and $1 for every $3 dollars of earnings over $46,920. Many people treat the earnings test as equivalent to a tax on earnings, even though future benefits are increased at Full Retirement Age.

“The case for eliminating the earnings test is largely based on its complicated nature, the confusion that surrounds it, and the ensuing distortions in labor market decisions,” wrote Shoven and Clark.

Second, these economists say, people should be considered “paid up” for Social Security once they hit Full Retirement Age. In other words, the employer and the employee would then be exempt from the Social Security payroll tax. Result? Higher take-home pay for the older workers and a lower cost of employing them for the employers. Shoven and Clark would eliminate the Medicare payroll tax at Full Retirement Age, too.

Third, they say, Medicare should automatically become your primary health insurance payer if you’re working at 65 or older. Your employer-sponsored health plan would then become the secondary payer. Employers would like this because they wouldn’t be on the hook to pay older workers’ health costs as much as they are today.

Give older workers with low incomes the ability to claim the Earned Income Tax Credit. This is an idea pushed by economists Alicia Munnell and Abigail Walters in Proposals to Keep Older People in the Labor Force. This tax credit has been effective at increasing the labor force participation rate among low-income mothers with children. But workers age 65 to 70 aren’t allowed to claim the tax break. Munnell and Walters would expand the age of eligibility and hike the maximum benefit for childless workers to $2,000.

Taken altogether, economists say, the costs of these ideas would be more than covered by tax revenue generated by higher rates of labor force participation and decreased use of public assistance.

Reframe the retirement decision. The very nature of Social Security’s “Full Retirement Age” causes many people to think that’s the point when they should start claiming their benefits. Yet their Social Security checks would be substantially larger if they could afford to wait until 70. “The message given to older people should be that their maximum benefit comes at age 70 and, though they can collect benefits earlier, this comes at a price in lower benefits for life, and perhaps lower benefits for their spouse,” wrote Baily and Harris.

Munnell and Walters have a retirement reframing proposal for 401(k)s, too. Tell employees how much their 401(k) balances might provide in monthly retirement income instead of just showing a total of how much is in the accounts. This would be a wake-up call for many workers, likely persuading some to stay on the job longer, if their bosses let them. The retirement legislation wending its way through Congress, known as RESA, includes such a requirement.

Take a 401(k) balance of $135,000 — the median for households with 401(k)s and IRAs nearing retirement in 2016. While that may seem like a decent amount of cash, it produces only about $630 per month in income (if it’s annuitized).

And here are two ideas that could make people in their 50s and 60s more valuable and engaged workers: Bailey and Harris urge more training opportunities for older workers, especially for upgrading digital skills. And in their paper Help People Work Longer by Phasing Retirement, Brookings scholars Joshua Gotbaum and management consultant Bruce Wolfe make a strong case for establishing the “legal right” to phased retirement — gradually reducing the number of hours you work until you ultimately stop working altogether. They propose amending the federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act to say that “failure to offer phased down part-time employment prior to retirement could, in certain circumstances, be found to be age discrimination.”

What are the odds that some of these proposals will become law? My best guess is that some will, because policymakers will take them seriously.

For example, it’s well-known on Capitol Hill that the Earned Income Tax Credit is overdue for reform. It isn’t hard to imagine that reworking it could come with eliminating the ban for people 65 to 70. And the Social Security earnings test is unpopular. Employers would likely rally behind a Congressional attempt to make Medicare the primary insurer of workers 65+.

Perhaps I’m an eternal optimist. But with the demographics of our aging population, incentives to work longer should appeal to liberal legislators concerned about retirement fragility and policies that reduce the demand for public services would be attractive to their conservative peers.