U.S.Tennis Great Alice Marble's Moment of Glory and the Aftermath

A new book, 'Queen of the Court,' looks at Marble's winning legacy and how her crown became tarnished

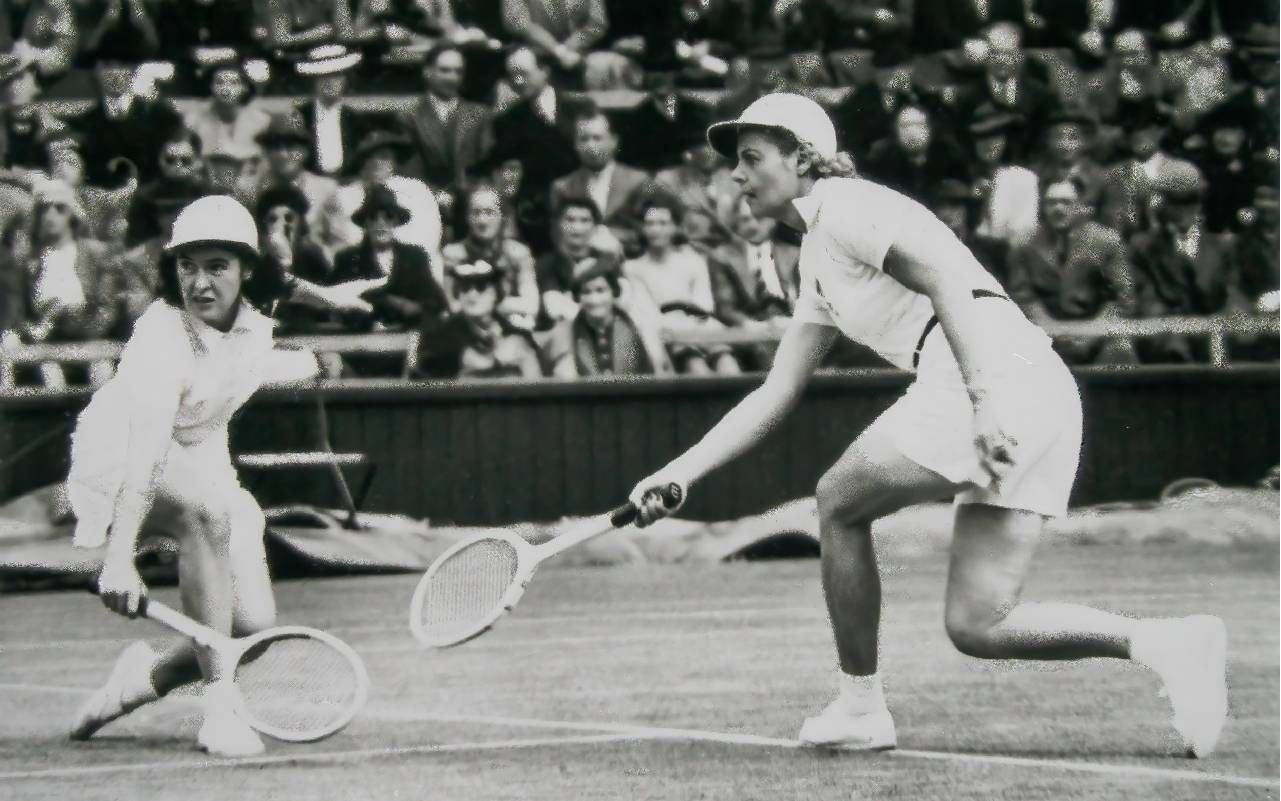

In the 1930s, U.S. tennis great Alice Marble broke new ground for female athletes with her success on and off the courts. Known for her powerful serve-and-volley style, Marble peaked as a player in 1939, when she claimed the singles, women's doubles and mixed doubles at Wimbledon and the U.S. Championships (now the U.S. Open).

Despite coming from humble roots, Marble also became internationally known, creating her personal "brand" decades before the term was used. She designed her own clothing line, performed a singing act at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City and even appeared in the Spencer Tracy-Katharine Hepburn movie, "Pat and Mike."

"It's not just the moment of great glory but it's what happens afterwards."

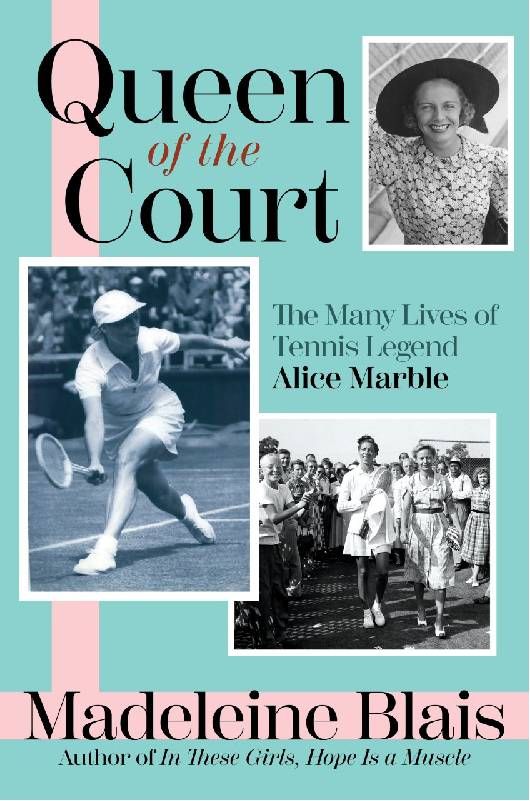

But as Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Madeleine Blais writes in the new biography, Queen of the Court: The Many Lives of Tennis Legend Alice Marble, her star quickly faded after World War II. Marble eventually worked a series of regular jobs, including as a medical assistant and swimming pool manager.

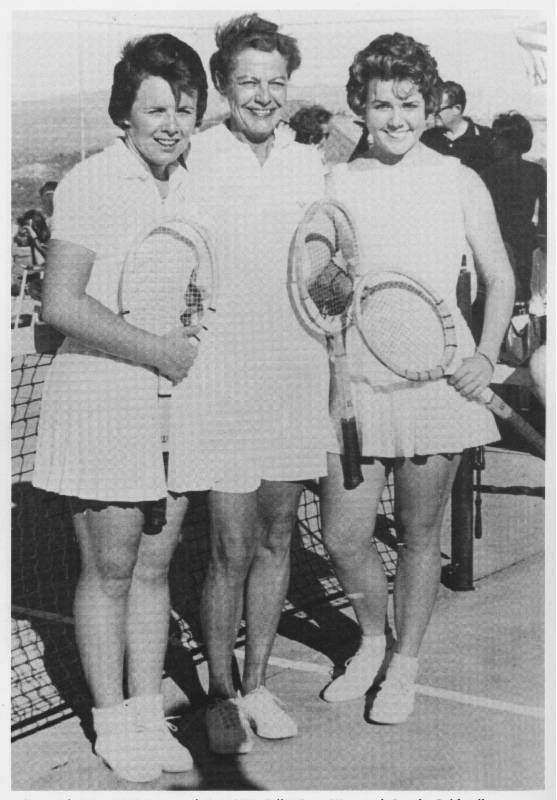

She would return to the spotlight on occasion, including as a key advocate to allow Black players to compete at the U.S. Championships, and as an early coach of another future Hall of Famer, Billie Jean King, but she was largely forgotten by the public.

As big as her life had been, Marble, who died in 1990 at age 77, also felt the need to embellish it, including the claim that she had spied for the U.S. during World War II.

Blais talked to Next Avenue about the scope of Marble's celebrity, her commitment to equality in tennis and the challenge of sorting the truth of her story from the fiction.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Next Avenue: What attracted you to Alice Marble's story and why did you decide her story was ready for a fresh retelling?

Madeleine Blais: One of my editors put her name before me as a possible subject. I looked into her, and I got a better sense of the basic arc of her story. It was an easy yes. I really like subjects that include the aftermath of their fame. It's not just the moment of great glory but it's what happens afterwards.

Alice Marble offered that because the height of her fame was in 1939 when she won Wimbledon and what we now call the U.S. Open. People in her orbit know who she was but outside it not so much. I also had a sense of the sadness in Marble's life when all of her fame had vanished, and her body had betrayed her with quite a few illnesses.

You write that Alice Marble's is a 20th century story. Can you put her fame in context?

There were not that many women who rose to the level she did. Partly for that reason, she became very famous. She was a celebrity before we had celebrities up and down the street. Her coach [Eleanor "Teach" Tennant] was a woman who understood the power of the press and PR; she not only wanted her to play great tennis but to present a certain image.

By the time she got under her spell, it was like a chameleon situation where Alice Marble became one of the most glamourous women in the world. She was as famous as Seabiscuit the horse. She was Kardashian-known and Meghan Markle-known in a time when it wasn't that common.

It has to be somewhat unbalancing to be that famous. It must be strange to come from a very working-class background — this is not a family that took anything for granted — and yet she was swept along and met movie stars and kings and queens and FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt. Her life was filled with celebrities even when her own celebrity faded.

Why do you think that someone as colorful as Alice Marble could then fade from public view?

This is the story of a woman experiencing the American century, not a man, and she would have certain limits on things that a man wouldn't. She stayed in the public view through the war because she did quite a few exhibition matches. She was well known as a woman who raised morale by going to various military installations to play tennis. But when the war ended, her tennis career had ended and opportunities to stay connected to tennis ended.

"This is the story of a woman experiencing the American century, not a man, and she would have certain limits on things that a man wouldn't."

Her coach worked with other tennis greats, like Maureen Connolly, but also was criticized for her tactics. What was your sense of her coach's relationship with Alice Marble?

I found the coach fascinating because she had so much power over the young Alice Marble. In the end, Billie Jean King said 'I'm not sure if that coach did Alice Marble any favors.' Billie Jean King remembers Alice Marble, when she was in her cups (drunk), telling a story about being at Wimbledon in her teens. She wanted a cookie, and the coach wouldn't let her have it and was controlling her weight by the ounce. That kind of self-discipline has to come from within; the coach needs to bring out the best in the athlete, but not own them.

Marble's commitment to diversifying the all-white sport of tennis is probably one of her lasting achievements. What motivated her in 1950 to push the all-white U.S. Lawn Tennis Association to let Black player Althea Gibson compete in the U.S. Championships?

I think she was born with a sense of fair play and a sense of gratitude for what had been given to her. She didn't need to belong to a club or have a backyard with a tennis court. She learned to play tennis in public courts, and while I don't have a huge sense of her mother, there are a couple of incidents where I think her mother had high standards she gave her daughter.

Given how much she accomplished, why do you think Alice Marble felt the need to exaggerate or even make up details about her early family life, her alleged marriage and her now disputed role as a spy?

She stayed single, but Alice Marble seems to have had a fantasy that she was married briefly during World War II and she carried out the fantasy of this wonderful husband who died during the war, and who [herself] gets inspired to also do a heroic mission as a spy. These are the two big categories of her life where she presented herself in a larger than life and heroic light and they appear to have been made up.

They were part of who she thought she was until the day she died. Honestly, I don't have the answer [as to why]. I'm absolutely curious what readers will think. There's no one who knows her story who doesn't want [the circumstances] to be true.

What was it like for you as a biographer to explore these inconsistencies and contradictions?

In nonfiction, you have to consider any roadblock to be an opportunity — that is truly part of the creativity of nonfiction. You can't make up an explanation for things. You can't change the details of someone's life. You have to research and find out why things are the way they are.

You have to think about how you can create a narrative where you don't let this roadblock ruin everything. Better than that, you try to make that roadblock your friend and try to use the inconsistencies to create a more textured biography. It's her story as it could be authenticated by research and her story as she lived it in her head.